Composting plant looks for new home

HILO — Expressing frustration with what they called a lack of communication from Mayor Harry Kim over a multimillion-dollar composting contract, members of the County Council took unanimous action Wednesday on two measures to try to keep a hand in contract negotiations.

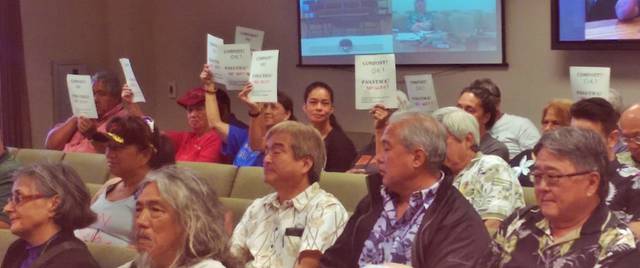

While trying to ensure the contract moves forward, the council at the same time attempted to reassure a packed crowd of Keaukaha and Panaewa residents who oppose the plant in their neighborhood.

Residents testifying mostly said they favor the plant, just not near their homes.

“It should not be near our community or near your community,” said Maile Luuwai, president of the Keaukaha-Panaewa Farmers Association. “Facilities like this should not be located near any community on this island.”

Luuwai later told the council she visited a similar site in Everett, Washington. She said the product was “compost gold,” but the process “smells like a big hog farm.”

There’s a way to oppose Kim’s pending cancellation of the 245-page contract while also requiring the proposed site be moved away from its planned location near the Hilo landfill, council members said.

Hilo Councilwoman Sue Lee Loy, who represents the region, inserted language in two resolutions removing reference to a specific location for the project, to give the administration an opportunity to find different sites.

“If we’re going to be part of the process, I included language to be sure it would not be located in Panaewa,” Lee Loy said. “It’s not profits. It’s people.”

Kim, who addressed the council five hours into their deliberations, said the county would continue with its current mulching projects at Kealakehe and the two county landfills. In the meantime, he said, his administration will look for a new site and continue negotiating the costs, a process that could take two years.

“If I don’t cancel this contract, what is my bargaining position with regards to his contract,” Kim said.

Kim said he’s also withdrawn the environmental assessment from the state. The EA had stated there were no concerns from surrounding community members. A new, more involved, environmental impact statement will be completed on new proposed sites, he said.

Hawaiian Earth Recycling was the only company responding to a request for proposals issued by the former administration. Under the terms of the 10-year contract, the county will pay $10.4 million for the construction of the facility, and pay a tipping fee for organic waste delivered to the facility, with the contractor able to sell both the mulch and the resulting compost to the public.

A company spokesman could not be reached by phone by press time Wednesday.

Kim, who questioned the facility’s cost and location, on Feb. 16 issued a “termination for convenience” notice, effective June 30. He said Friday he’s begun renegotiation with the company, but the termination notice hasn’t been rescinded.

“If these negotiations fail and it ends up in court, we don’t want to be on the hook,” said Puna Councilwoman Eileen O’Hara. “The county could be held liable for many millions of dollars.”

“You can’t just willy-nilly say we’re going to cancel the contract for our convenience,” added Hilo Councilman Aaron Chung.

Council members also see the compost facility as an important part of the county’s solid waste management plan. Chung called the concept “transformative.”

“We’re going to be turning rock into arable land,” Chung said.

Two former council members urged the council to keep the project moving forward, while finding a better place to put it. The West Hawaii landfill at Puuanahulau would be one place to put it, but the lack of potable water is a hindrance, the administration has said.

Former Kohala Councilwoman Margaret Wille said the dry side of the island would welcome the facility as a source of soil amendments to hold precious water, provided there’s sufficient buffer from communities.

“Realize how important compost is to the future of the island,” Wille said. “North Kohala wanted a composting facility here, Waikoloa wanted a composting facility there and people in Hamakua.”

“That community has literally been dumped on for decades,” said former South Kona/Ka‘u Councilwoman Brenda Ford, adding, “when the county signs a contract, our word should be gold.”

Resolution 134 gives the council authority to spend up to $50,000 on an outside attorney to evaluate the composting contract and county liability if the contract is canceled. Resolution 135 is a nonbinding resolution urging the mayor to rescind the notice of termination. Both passed 9-0.

Resolution 101 would give the administration permission to go out for new bids on a composting project. Rather than killing the resolution outright as was voted in committee, the council postponed the measure for two weeks, forcing the administration to come back with an update on contract negotiations.

“This in my eyes is a unified attempt to engage not only the community but it also engages this body and engages the mayor and his department heads,” said South Kona/Ka‘u Councilwoman Maile David, “for the betterment of the community.”

Testifiers showed maps, described rainforests, talked about annual rainfall. Longtime resident Luahiwa Namahoe pointed out the swath of rainforest in the Keaukaha and Panaewa region that has steadily been consumed by developments. In particular, she noted, the Hilo landfill, the airport, a Mass Transit baseyard and a drag strip have eaten into the forest.

“I grew up surrounded by other people’s waste,” she said.

Wallace Ishibashi, a member of the board for the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands who was born and raised in Keaukaha, said he’s always been pro-development as a longtime labor leader. But development doesn’t always have to be to the disadvantage of Native Hawaiians, he said.

“How we used to develop our lungs was to hold our breath as we passed the sewer plant,” Ishibashi said. “Hawaiians are giving people. We give and give and give and give and give. But it’s growing thin.”