HALEAKALA NATIONAL PARK — Well before dawn each morning, throngs of tourists from around the world make their way to Maui’s tallest peak, a dormant volcano, to see what Mark Twain called the “sublimest spectacle” he ever witnessed. ADVERTISING HALEAKALA

HALEAKALA NATIONAL PARK — Well before dawn each morning, throngs of tourists from around the world make their way to Maui’s tallest peak, a dormant volcano, to see what Mark Twain called the “sublimest spectacle” he ever witnessed.

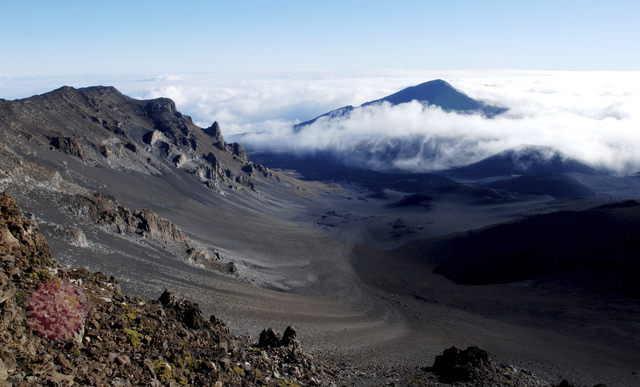

They drive up a long, winding road through the clouds to an otherworldly, lava-rock landscape at 10,000 feet. Then they bundle up and take their place for a dazzling daybreak show.

“Just the sunrise from the top of the world — it’s pretty remarkable and incomparable,” Julia Grant of Mission British Columbia, Canada, said on a recent visit after watching the sun peek out from the horizon and saturate the sky in endless shades of yellow, orange and red.

Over the past year, the sunrise view from atop Haleakala — Hawaiian for “House of the Sun” — has been attracting over a thousand people a day. The result, officials say, was a logjam of cars spilling out of the parking lots and onto the road, creating a safety hazard, and footsteps trampling sensitive habitat.

To address the problem, the National Park Service this week started requiring reservations and limiting the number of vehicles to the available parking spots, potentially cutting in half the number of early-morning visitors.

Sunrise viewing has long been popular at Haleakala, one of the main attractions at Haleakala National Park, despite morning temperatures that often dip into the 30s. Red soil and lava rocks dominate the summit, and only a few hearty plants have adapted to the harsh, high-altitude conditions. The peak also is home to the nene, the Hawaiian goose, and colonies of spiders that feast on bugs blown in from the surrounding wilderness.

Overcrowding started becoming a problem roughly 15 years ago, park superintendent Natalie Gates said. About a year ago, it got worse, likely as more people learned about the stunning sunrise views from images shared on social media.

“If you ever went up there, you would see that fully half to three-quarters of our visitors who are watching the sunrise are either taking photos that they immediately broadcast to their friends, or filming it,” Gates said.

The area at and near the summit has 150 parking spaces, but before the new system took effect, more than 300 rental cars and other vehicles often crammed onto Haleakala at daybreak. Drivers who couldn’t find a spot would park on the side of the road or on the road itself, blocking the way for emergency responders.

Though only 16 percent of park visitors come at sunrise, they account for 40 percent of the park’s emergency medical calls.

“It’s a dark place. It’s rocky. And when people are moving away from crowds and trying to go off trail, often frequently stumbling around on cliff sides in the dark, we see trauma cases, altitude cases,” Gates said. “We sometimes see cardiac and other cases.”

Straying humans also trample on seedlings and root systems of the Haleakala silversword, a rare, bush-like plant with thick leaves. And they can disturb the ground nests of the Hawaiian petrel, an endangered seabird.

Under the new system, only those driving to the summit between 3 and 7 a.m. need reservations, which cost $1.50 per car plus the $20 park entrance fee.

The system closes to sunrise viewers after the allotted 150 vehicles per morning have made their reservations. The proceeds will pay for the expense of administering the reservation program. People on guided tours won’t be affected as tour companies fall under different regulations.

Reservations can be made up to two months in advance at the website recreation.gov. Other national parks with similar programs include Yosemite in California, which limits the number of people who can hike to the top of its iconic Half Dome rock formation.

The change will require adjustments from people who don’t normally plan ahead, said Carol Clark, Maui Visitors and Convention Bureau spokeswoman. But her agency believes the benefits far outweigh any inconvenience.

Nettie Kuwamura, a Native Hawaiian who was born and raised on Maui, considers herself a protector of the summit. She reminds tourists to stay off the lava rocks and away from fragile areas.

“I’m passionate about this island. I’m passionate about this mountain,” Kuwamura said. “It’s a very sacred mountain to the Hawaiians.”

For the past two years, Kuwamura has been driving tourists to the summit, where she recites a Hawaiian chant to welcome the rising sun each morning.

“Once the sun comes up, that’s when the beauty comes up,” she said.

———

McAvoy reported from Honolulu. Associated Press writer Brian Skoloff contributed to this report.