Kyle Kinoshita knew from an early age that he was good with his hands. ADVERTISING Kyle Kinoshita knew from an early age that he was good with his hands. “I used to always take apart things and build things,” he

Kyle Kinoshita knew from an early age that he was good with his hands.

“I used to always take apart things and build things,” he said, referring to toy models. “I would throw away the instructions and I would just build one.”

But the Hilo High School grad never saw himself building something quite like this.

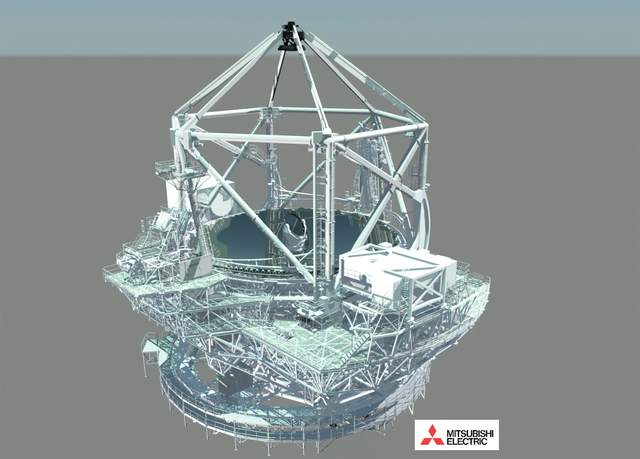

As the telescope structures group leader for the Thirty Meter Telescope, Kinoshita is responsible for overseeing design and construction of an integral part of the controversial project proposed for Mauna Kea. And one of its most costly.

Kinoshita, 55, who previously worked for the W.M. Keck Observatory, estimated it will come with a price tag of $200 million to $300 million, a significant chunk of a project estimated at $1.4 billion prior to delays.

Nothing quite this large has been built for a telescope before.

The structure, which holds the instruments and the 492 segments that will comprise its massive primary mirror, will weigh 2,000 metric tons, he said. That’s about five times the weight of the Keck telescope structures, currently some of the world’s largest.

Aside from the 180-foot-tall dome, it’s the biggest piece of the puzzle.

If only he knew where all of it would go.

With the telescope once again going through a contested case hearing, which will help determine whether its land use permit for Mauna Kea’s Conservation District is reapproved, there remains a cloud of uncertainty hanging over the project.

The TMT International Observatory board of directors has sought alternate spots in case the permit application is denied, including Mexico, the Canary Islands, Chile, India and China.

“I know for sure it has affected us by about a couple years already,” Kinoshita said.

He said that while the telescope structure, which will be built in Japan, is in the final design phase, the setbacks means that could take a couple more years to finish.

Without a dedicated spot to build, the project’s partner countries — United States, Canada, Japan, China and India — aren’t able to commit as much funding.

“Basically, Japan has said no fabrication for the telescope structure until a site, until certainty is given,” he said.

A change in location shouldn’t change the telescope structure’s design, but there are trade-offs being considered for other aspects of the project, Kinoshita said.

“You kind of move forward,” he said. “You do what you can.

“But in the back of your mind, you are just having this uncertainty of where you are going to go. It’s hard.”

Kinoshita is still hopeful the next-generation observatory, which faces opposition from some Native Hawaiians who consider the mountain sacred and environmentalists, will call Hawaii its home.

“TMT is basically the future,” he said. “It’s the future of world-class astronomy. … You will have the best facility in the world for another 20-30 years.”

Either way, he looks forward to seeing it reach first light.

“It’s like putting your car project together and then turning on the keys,” said Kinoshita, who repairs hot rods as a hobby.

“For this thing to come together, all the different parts, yeah, it’s almost inconceivable.”

Email Tom Callis at tcallis@hawaiitribune-herald.com.