The neighborhood beyond Neptune is becoming ever more crowded, with astronomers announcing this week the discovery of another likely dwarf planet. ADVERTISING The neighborhood beyond Neptune is becoming ever more crowded, with astronomers announcing this week the discovery of another

The neighborhood beyond Neptune is becoming ever more crowded, with astronomers announcing this week the discovery of another likely dwarf planet.

A survey at the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope atop Mauna Kea has been tracking more than 600 bodies in a ring of icy debris known as the Kuiper belt. One of them turned out to be the likely dwarf planet.

“This is a big fish among a whole lot of small ones we’re working with,” said Michele Bannister, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Victoria in British Columbia who is working on the survey.

In the year since NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft flew past Pluto, planetary astronomers continue to make discoveries in the Kuiper belt. The study of these objects also offers hints about the formation and migration of the gas giant planets: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

Even if the newly found world is a dwarf planet, however, it will probably be years before it might earn official designation — part of the confusion of definitions that followed the International Astronomical Union’s decision in 2006 to demote Pluto and reduce the solar system to eight planets from nine.

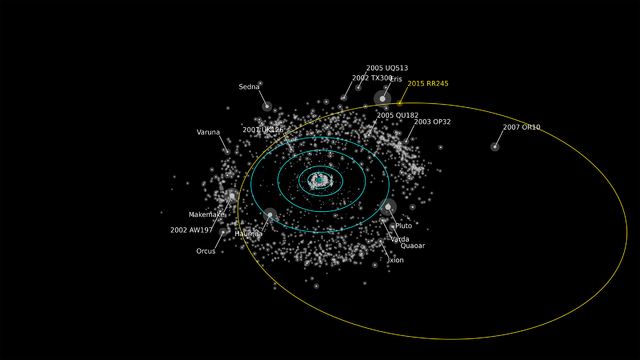

More than 100 bodies in the solar system, all but one located along the ring of icy debris beyond Neptune, appear to meet the definition of a dwarf planet, a category that the astronomical union created to describe Pluto as well as Ceres, the largest asteroid, and Eris, a Kuiper belt object slightly smaller than Pluto. (A full-statured planet has an additional requirement: It must have “cleared the neighborhood” of smaller debris.)

If dwarf planets were to be reclassified as planets, as advocates for restoring Pluto to full planethood status hope to do, forget about trying to devise a workable mnemonic device.

The new object, designated 2015 RR245, was first spotted in February as the astronomers looked through images taken five months earlier. Further observations a few weeks ago confirmed the object’s 700-year loping path around the sun.

The astronomers cannot directly measure the object’s size. Rather, from its brightness, how far away it is and an assumption of how reflective its surface is — most Kuiper belt objects are roughly the darkness of coal — they estimated the diameter to be 370 to 500 miles.

They also cannot directly tell if 2015 RR245 is round. The definition of a dwarf planet requires that the gravity is strong enough to pull the body into the shape of a ball.

Mimas, a 250-mile-wide icy moon of Saturn, is round, and it is likely that the much larger 2015 RR245 is also round.

The astronomical union has been slow to designate new dwarf planets, adding just two since 2006: Haumea and Makemake. But there are a slew of additional Kuiper belt objects larger than Mimas.

If its estimated diameter is accurate, 2015 RR245 would rank as just the 19th largest potential dwarf planet. Larger objects include Quaoar, Orcus, Salacia and still-unnamed objects with temporary designations like “2007 OR10” and “2002 MS4.”

“I hate to say any Kuiper belt object is uninteresting, but it’s a typical Kuiper belt object that is in the top 20 biggest ones,” said Michael E. Brown, a professor of planetary astronomy at the California Institute of Technology who discovered Eris and most of the larger Kuiper belt objects through a sky survey a decade ago. “This one is no more or less bizarre than most of them.”

Brown’s computer keeps track of large Kuiper belt objects, and 96 of them appear to be larger than Mimas and thus most likely to be round dwarf planets. Another 300 are smaller but possibly could still be large enough to be round.

Dwarf planets are “not a rare class of objects in the outer solar system,” Brown said.

© 2016 The New York Times Company