ATLANTA — The decision by the owner of a small insurance company to require his employees to carry firearms at the office has sparked a debate: Would having a gun on the job make you safer, or is it inviting

ATLANTA — The decision by the owner of a small insurance company to require his employees to carry firearms at the office has sparked a debate: Would having a gun on the job make you safer, or is it inviting violence into the workplace?

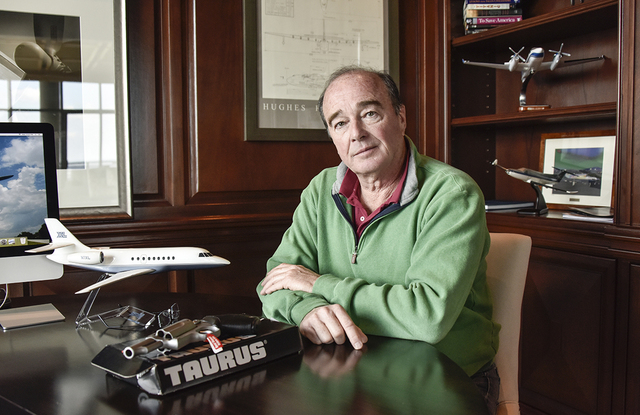

Lance Toland said his three offices, based at small airports in Georgia, haven’t had problems with crime but “anyone can slip in these days if they want to. I don’t have a social agenda here. I have a safety agenda.”

When a longtime employee, a National Rifle Association-certified instructor who’s been the company’s unofficial security officer announced her retirement, Toland wanted to ensure the remaining employees were safe. He now requires each of them to get a concealed-carry permit, footing the $65 bill, and undergo training. He issues a Taurus revolver known as “The Judge” to each of them. The firearm holds five rounds, .410 shells that cast a spray of pellets like a shotgun.

“It is a weapon, and it is a lethal weapon,” said Toland, whose company specializes in aviation insurance. “When a perpetrator comes into the home or the office, they have started a fire. And this is a fire extinguisher.”

No employee balked at the mandate, he said. “They all embraced it 100 percent, and they said, you know, I’m tired of being afraid,” Toland said.

An employer’s legal standing to impose such a requirement depends on several factors, foremost whether the business is high risk, a convenience store or taxi company, for example, said Carin Burford, a labor lawyer in Birmingham, Alabama.

More than 400 people on average are killed in the workplace each year, according to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics. Just last week, a gunman with a criminal record who had just been served with an order to stay away from his former girlfriend began a shooting spree, eventually landing at the lawn mower parts factory where he worked. Authorities say he killed three people and wounded 14 others before a police officer shot and killed him.

About half of U.S. states have laws allowing people to keep firearms in their cars at work. There are companies that allow employees to bring firearms to the office. But it’s rare to hear of an employer making it a requirement.

Kevin Michalowski, executive editor of Concealed Carry Magazine, said he hasn’t heard of any companies issuing a mandate, but he’s increasingly hearing from companies, churches and schools seeking training so they’re prepared to deal with a workplace shooting.

He said while workplace shootings don’t happen every day, when they do happen, people should have the ability to protect themselves — particularly before police are able to respond.

One person who isn’t convinced is Charles G. Ehrlich, an attorney in California. He was working for the Pettit &Martin law firm in California on July 1, 1993, when Gian Luigi Ferri, a failed entrepreneur and former client of the firm, arrived at the high-rise office building with multiple weapons, killing eight people and injuring six before killing himself.

Ehrlich was lucky. A meeting he was attending went long, and he didn’t end up down the hall in a conference room that was Ferri’s first target. “I heard the shouting and the noise” but had just moments earlier left the floor.

“It’s not like it is on TV or at the movies where the good guy just shoots the bad guy,” said Ehrlich, the former president of the Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. “It’s very difficult to shoot a gun accurately, even when you’re not under pressure.”

Ehrlich also worries about the pressure cooker that exists in many workplaces — and that arming more employees might actually lead to more workplace shootings.

“Conceivably, someone who was well-trained — an ex-Green Beret or something like that — could’ve run down the hall, pulled out a weapon and fired a shot,” he said of the shooting at the firm. “But would he have prevented anyone from being killed? No. Unlike John Wayne, who is always faster than the other guy, this guy got off the elevator and just started shooting.”

Playing in the back of Toland’s mind was something personal: A beloved uncle who had adopted him as a child was killed in 1979 during a nighttime robbery at the convenience store where he worked. Three men robbed him of less than $100. It was the first day he hadn’t brought a firearm to the store.