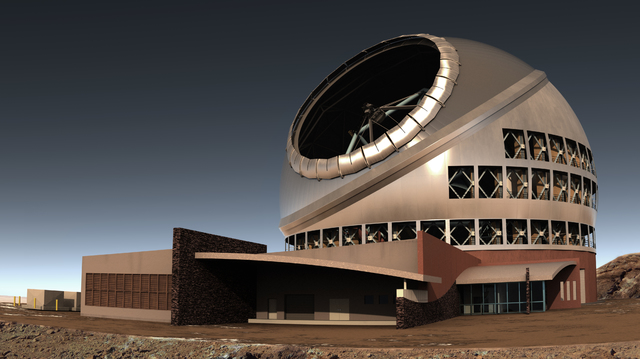

HILO — Scientists say that last week’s state Supreme Court ruling on the Thirty Meter Telescope puts not only that project’s future in limbo, but also jeopardizes observatories already atop Mauna Kea. ADVERTISING HILO — Scientists say that last week’s

HILO — Scientists say that last week’s state Supreme Court ruling on the Thirty Meter Telescope puts not only that project’s future in limbo, but also jeopardizes observatories already atop Mauna Kea.

“We’re on the edge … between having a profound impact, sociologically, worldwide, with this really fundamental research about the universe occurring right here on the Big Island, and the whole thing just sort of collapsing under an inability as a people to recognize its value and to work that into the future of Mauna Kea,” Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope Executive Director Doug Simons said Monday.

State Supreme Court justices ruled Wednesday that the Hawaii Board of Land and Natural Resources erred when it prematurely issued a construction permit for the $1.4 billion telescope. The high court remanded the project back to a contested case hearing.

Having already begun site preparation work in October 2014, construction ground to a halt in the face of public protests. Now, the ruling sets the construction project back months, and perhaps years. It was a major victory for opponents of the telescope project, who say that it would desecrate sacred ground.

According to Simons, the international consortium of universities has so far shown great fortitude as it has shepherded the TMT through hearings, public meetings, and more. But their patience may have been worn thin by this latest defeat.

“There’s a possibility of it getting resolved from a permitting standpoint,” he said. “But then there’s the question of how much longer can they go on. That’s up to TMT to answer. At what level has their patience expired with the process? For the better part of a decade now, they’ve been grinding through a labyrinth of permitting steps.”

Financial considerations, public pressure and time constraints could all serve to shut down TMT. But even more worrisome, he said, is the fact that, should the telescope fail to reach fruition, the ongoing work using the 13 telescopes currently in operation on the mountain could be impacted.

“I can’t think of any field of science where Hawaii has dominated, or had a sort of pre-eminence worldwide, like astronomy today. And we may never have that chance again, for all I know,” Simons said. “… If we can’t get our collective act together and even protect the master lease renewal process for Hawaii astronomy, we’re talking about losing what we’ve already got and losing that pre-eminence, and losing all of the positive impact on the Hawaiian state and the people, as a result of that. These are really stark potentials. … The master lease is the holy grail in all of this.”

The current 65-year master lease agreement between University of Hawaii and the state to operate on the Mauna Kea Science Reserve expires in 2033, and if it is not renewed, astronomy could be set back indefinitely, he said.

Despite his concerns, however, Simons says that he remains optimistic, calling the disagreements over use of the mountain “not insurmountable.”

This summer, as part of the master lease renewal application, UH outlined its plan for improving stewardship of Mauna Kea, including a commitment to reduce the number of observatories on the mountain by the time the TMT is expected to be complete.

And if TMT can continue to share its message that Hawaiian cultural traditions and scientific exploration can continue to co-exist on the mountain, the telescope may still be built successfully.

“If people saw the value in each other’s perspectives, instead of being entrenched in our own comfort zones, we could build those bridges,” he said.

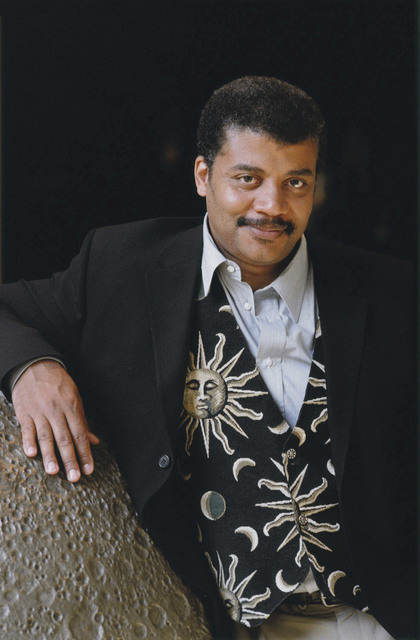

In a November interview with online news site The Verge, famed astrophysicist and science educator Neil deGrasse Tyson weighed in on the TMT debate, saying much the same thing. While being careful to tread lightly around cultural questions that he admitted knowing little about, Tyson said he saw a definite alignment between the goals of astronomers and the goals of Hawaiian cultural practitioners.

“What is specific to astronomers is putting a 30-meter telescope on a mountaintop that native people consider sacred. That’s fascinating to me, culturally and sociologically, because it’s a contest of values occupying the same space,” he was quoted as saying. “Normally you say, oh, you build your church here, I’ll build my church here, I’m not trying to build my church in your church. Or whatever that is. Generally, you can just separate people out. But because we’re talking about the same mountaintop, I’m curious how that will ultimately resolve.

“I can tell you that — and I’m revealing my astrophysics bias here, of course, but it’s still a thought to consider — that, well, what is it we’re doing on the mountain? We’re trying to understand how the universe got here. And that’s one of the questions that, I think, has been in practically every religion and every spiritual pursuit that has ever existed and ever been written about. So if that’s not the noblest thing to do with a mountaintop, I don’t know what is.”

Email Colin M. Stewart at cstewart@hawaiitribune-herald.com.