Child tax credit tussle reflects debate over work incentives

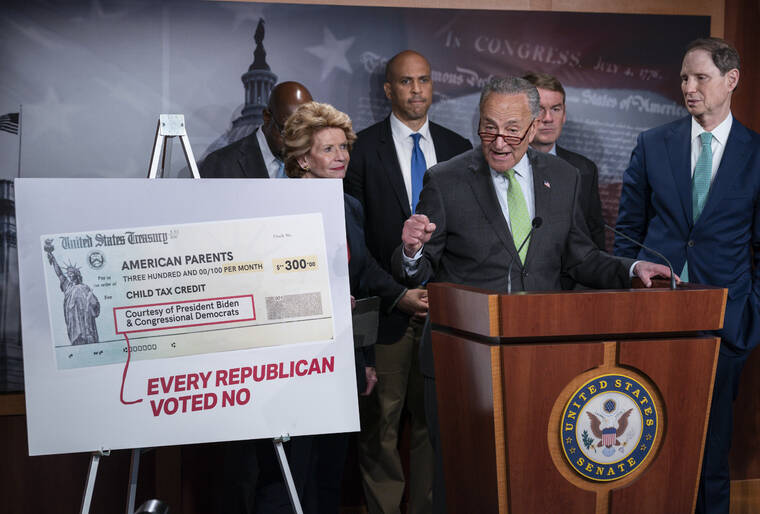

FILE - Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., holds a news conference to talk about the benefits of the Child Tax Credit, at the Capitol in Washington, Thursday, July 15, 2021. President Joe Biden and leading Democratic lawmakers have been fighting to make permanent a child tax credit that would give families at least $300 a month per child. But the latest budget deal would extend the payments through the end of the next year. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

WASHINGTON — To supporters of the child tax credit, there has always been an “aha moment” — the recognition that as little as a few hundred dollars a month could be life-changing.

WASHINGTON — To supporters of the child tax credit, there has always been an “aha moment” — the recognition that as little as a few hundred dollars a month could be life-changing.

For Colorado Sen. Michael Bennet, it was several years ago when he was working as Denver’s school superintendent. One high schooler kept falling asleep in morning classes. When Bennet asked why he was so exhausted, the student said he worked the midnight shift at McDonald’s so that his family had enough money.

For Connecticut Rep. Rosa DeLauro, it was the childhood memory of her parents being evicted and finding their furniture on the street.

Bennet and DeLauro are among the Democratic lawmakers who have pushed to make permanent an expanded child tax credit, which President Joe Biden’s coronavirus relief package transformed into a monthly payment that would be available to almost any child. But Biden could not convince even enough of his fellow Democrats that they should extend these payments through 2025, and in negotiations for his broader package of economic and social programs he appears to have settled for a one-year extension that runs through next year.

Despite the concession, the president is still fighting for a legacy-making policy that could become the equivalent of Social Security for children. Biden dubbed the start of payments in July as “historic,” saying that the reduction to child poverty would be transformative and that he intended to make the credit permanent.

The steady evolution of the child tax credit reflects a fundamental split on how lawmakers think about human nature. Do payments from the government make people lazier or give them the resources to become more responsible? Established with bipartisan support in 1997, the credit has changed in ways that challenge many of the assumptions of political identities, as Democrats would be the ones calling on Republicans to cut taxes.

Republican critics and West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin — the decisive Democratic vote — worry that the payments could discourage parents from working, while supporters say the money would make it easier to afford the child care and transportation needed to find jobs.

“It’s a flat-out tax cut for ordinary people,” Biden said in a Wednesday speech in Scranton. “That’s what it does. I make no apologies for it.”

The continuation of the payments of at least $300 a month per child is as much about a political transformation as an economic one.

For the purposes of the federal budget, it is a tax cut aimed squarely at the middle class as median family incomes are at $86,372. The credit’s evolution since being created in 1997 speaks to the power of using the tax code for social policy.

It allows Democrats to claim the mantle of middle-class tax cutters, while Republicans who oppose the idea could be criticized for favoring tax hikes on this key group of voters ahead of the 2022 elections. That is a sharp reversal from the Ronald Reagan-era identity of Republicans as committed to tax cuts for aiding growth.

“A lot of its initial success was that it did fit into the frame of tax relief,” said Gene Sperling, a Biden aide who worked on economic policy in both the Clinton and Obama White Houses. “This is one place where progressives have over a period of 30 years kind of won the conceptual war.”

The child tax credit was initially bipartisan, a unique policy overlap between former President Bill Clinton and former House Speaker Newt Gingrich.

Republicans made it part of their 1994 “Contract with America,” a list of polices that former Georgia Rep. Gingrich rode to the House speakership. Gingrich said in an interview that former Illinois Rep. Henry Hyde, a staunch abortion opponent, emphasized that the GOP needed to show that it cared about children after they were born, not just when they were in the womb. The tax credit was the chosen vehicle.

Clinton separately proposed it in December 1994 in his “middle class bill of rights” speech. The convergence ultimately led to the 1997 overhaul of welfare that established a $500 tax credit for children. Future administrations expanded the credit. But until this year the credit was not “fully refundable” — which meant that parents with low incomes might not earn enough to receive the full payment.

What Biden and Democratic lawmakers did with their coronavirus relief package was remove that limit, effectively turning the tax credit into a monthly child allowance. Their planned extension would make this change permanent.

Gingrich and Republicans say people would quit their jobs because they would be able to receive payments without working, depriving children of working parents who can serve as role models.

He calls that “an enormously dangerous thing for our culture.”

Backing that argument is a paper by University of Chicago economists that assumes the expanded tax credits would cause 1.5 million parents to ditch their jobs because the credits would no longer be tied to working.

“It’s a policy that’s been transformed from one that encourages self reliance and work to one that doesn’t,” said Bruce Meyer, the University of Chicago professor who co-wrote the analysis.

However, real world economic data shows no correlation between the payments and people leaving work so far. Researchers at Columbia University have found that the expanded child tax credit payments that began in July had no impact on labor and that models claiming otherwise are overly simplified. Workers often need to spend money in order to get a job, they reason.

“You have to make an investment in order to be able to work,” said Elizabeth Ananat, an economist at Barnard College who co-wrote the Columbia paper. “You do have to get your car fixed. You have to get your phone turned back on. You have to buy a month supply of diapers in order to secure your spot in the preschool.”

Democratic lawmakers believe the payments reduce poverty and improve educational outcomes, making it more likely that the children will hold steady jobs as adults.

Colorado Sen. Bennet backed the idea of a child tax credit after he found as a school administrator that more resources were needed to ensure kids had the stability to succeed.

“Most of the parents are working incredibly hard, some of them working two and three jobs. And no matter what they do, they couldn’t keep the kids out of poverty,” Bennet said.

DeLauro says the breakthrough on expanding the credit came as a result of the coronavirus showing how economically fragile many families are and Biden’s own choice as a presidential candidate to support the policy. She believes that beneficiaries will keep their jobs because work is part of who they are.

“People identify themselves by their work,” she said.