A decade ago, the Big Island won an additional seat in the state Senate following the 2010 census. This year, it’s poised to win an eighth House seat.

That’s if the data, scheduled to be released in August, follows the trends showing up in interim U.S. Census Bureau estimates, that Oahu’s growth has been lagging that of the neighbor islands, especially the Big Island. Full counts are made every 10 years, with the bureau producing estimates in the years between by surveying a sample of households.

“I would absolutely say that with the prospect of increased population here and it shrinking on Oahu, we’d get the seat, but until we see the final census numbers,” we won’t know for sure, said Waimea resident Patti Cook, one of five Big Island residents who sued over island representation after the last census.

“To me, it really is about our voice,” she said. “We’d love another seat but we have to be deserving of it.”

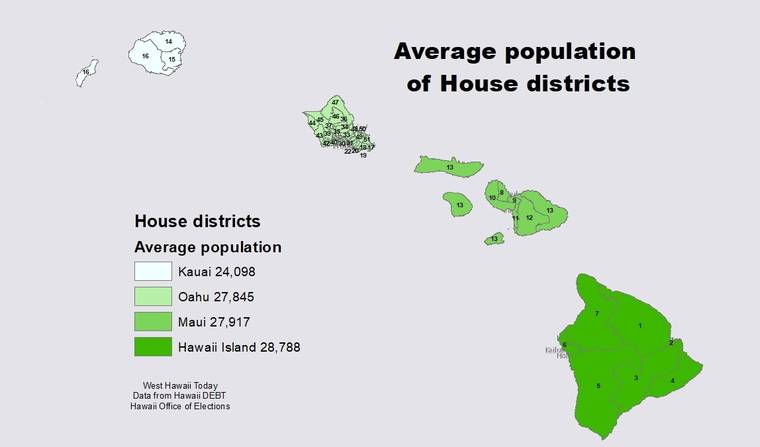

The most recent estimates show Oahu added 18,278 people between 2010, when the political boundary lines were last redrawn, and 2019. That means there’s an average 27,845 residents in each of Oahu’s 35 House districts.

The Big Island has grown the fastest and has the most-populated average House districts in the state, with 28,788 residents estimated in each of its seven districts. Maui comes next, with 27,917 estimated in each of its six districts. And Kauai’s three districts show an estimated average population of 24,098.

Will data or politics prevail during the drawing of the lines?

“It will just work out to whatever the calculation is,” said Dylan Nonaka, a Kailua-Kona real estate broker and the only Big Island member of the Reapportionment Commission — the nine-member body charged with setting boundaries for state legislative offices. “Until we get the data, we really don’t know.”

The point of reapportionment is to ensure equal representation for all residents. The goal is to draw legislative districts with as close to the same number of people as possible.

The data notwithstanding, political factors usually do enter into the mix. A group of Big Island residents successfully sued the state in 2011 to secure that fourth Senate seat after the commission added 108,767 nonresident service members, dependents and students into the count, most of whom lived on Oahu.

The Hawaii Supreme Court made the commission redraw the maps after the lawsuit by former state Sen. Malama Solomon, former Hawaii County Democratic Party Chairman Steve Pavao and party committee members Louis Hao and Cook. In addition, Kona attorney Michael Matsukawa filed his own lawsuit on behalf of the public.

Solomon and others are worried that the governor and the state Legislature may have preempted that ruling. A bill covering salary schedules, SB 1350, was amended at the last minute in conference committee, with both houses unanimously approving it, to add a definition leaving it open to add temporary residents such as military families and students.

Gov. David Ige on May 17 quietly signed the bill into Act 14.

The new law defines “permanent resident,” for the purposes of legislative reapportionment, as “a person having the person’s domiciliary in the State. In determining the total number of permanent residents for purposes of apportionment among the four basic island units, the commission shall only extract non-permanent residents from the total population of the State counted by the United States Census Bureau for the respective reapportionment year.”

Solomon said she talked with Ige and state Chief Elections Officer Scott Nago expressing her concerns. She’s also sent a letter to the Reapportionment Commission. She said the language in the new law is vague and ambiguous and could cause problems for the commission.

“Everybody’s been alerted, so we’ll see how it turns out,” Solomon said, adding if necessary, “we’ll kick it back to the Hawaii Supreme Court.”

Pavao, one of the litigants in the 2012 case who now sits on the Hawaii Island Advisory Council of the Reapportionment Commission, doesn’t think the new law is as big a problem as others do.

“I just hope the commission is transparent and follows the numbers,” Pavao said, “and doesn’t get involved in politics, politics.”

Nonaka said the commission plans to offer the public the chance to build their own maps once the numbers and the software are in place. Draft maps will be taken to each island for public hearings, he said.

The Hawaii County Committee of the county Democratic Party had unanimously voted to ask Ige to veto the bill. In a May 17 letter to party members, Hawaii County Chairwoman Barbara Dalton said the new law seems to contradict the Supreme Court decision.

“Specifically, the concern relates to how military personnel are counted in Hawaii. The U.S. Census counts all residents who consider a state their primary residence – i.e., where they live and sleep most of the time. However, it’s often the case that military personnel, though stationed in Hawaii, actually consider another state as their permanent domicile including where they vote,” Dalton said in the letter..

The state had 1,455,271 residents, up 94,970 from the 2010 census, according to state-level data the Census Bureau released last month.

The Supreme Court has presumed a plan is unconstitutional if districts are 10% larger or smaller than the ideal population, which is derived by dividing the total population by the number of districts. That means the ideal population of each of the 51 House districts in the state would be about 28,535, or, from 25,681 to 31,388 to stay within the 10% deviation.

It’s a daunting task for the Reapportionment Commission, which also strives to avoid the so-called “canoe districts,” where a state legislator represents parts of two or more islands. This has proven unsatisfactory to both the lawmakers and the residents, who feel their representation is diluted in comparison to having a state lawmaker represent a single island, opponents of canoe districts say.