Why US classrooms are starting to resemble arcades

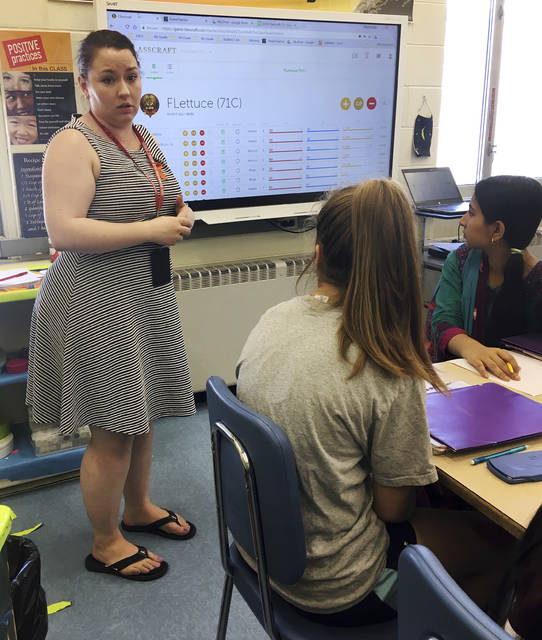

WALLINGFORD, Conn. — It’s 1 o’clock on a Wednesday afternoon in Wallingford, Connecticut, and about 20 children are watching a screen at the front of the room as they take turns navigating challenges and collecting virtual currency to unlock powers, outfits and pets for their characters.

WALLINGFORD, Conn. — It’s 1 o’clock on a Wednesday afternoon in Wallingford, Connecticut, and about 20 children are watching a screen at the front of the room as they take turns navigating challenges and collecting virtual currency to unlock powers, outfits and pets for their characters.

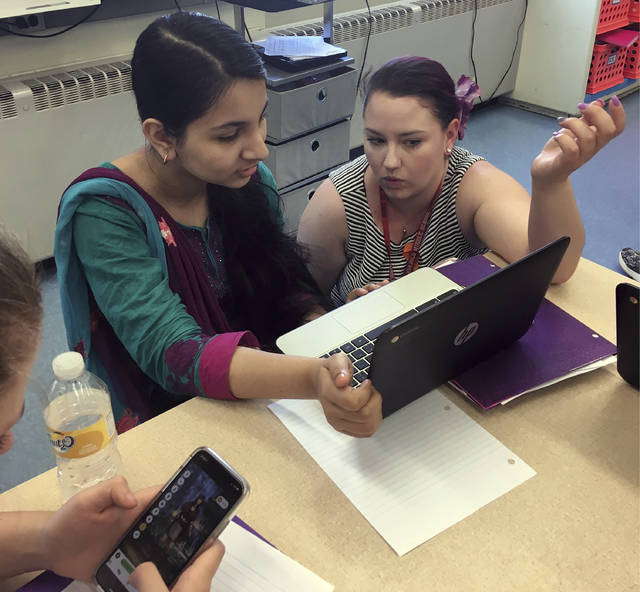

The game they’re playing has some similarities to the online battle game “Fortnite.” But the kids aren’t fighting one another — they’re racking up points for participation and good behavior in their classroom at Dag Hammarskjold Middle School, where their teacher is presenting a home economics lesson with help from Classcraft, a fantasy-themed educational program.

“It’s actually a lot of fun,” said 13-year-old Caiden McManus. “The pets — that’s my favorite thing to do. To train the pets, you gain as many gold pieces as possible so you can get the new outfits and stuff.”

Peek inside your average classroom these days, and you’re likely to see teachers using apps, websites and software that borrow elements from video games to connect with students living technology-infused lives. By all accounts, they’re fun to use, and studies have found that some can be effective. But there is also skepticism about how often students who use them are better educated, or just better entertained.

Dag Hammarskjold consumer sciences teacher Gianna Gurga said she had been looking for a way to get more out of her students. Students have been more motivated and performed better in her classes since she began using Classcraft in spring 2017, she said, and she has signed up a handful of other teachers in the school.

“My kids are so addicted to it in the best way possible,” Gurga said.

In one session, the classroom filled with suspenseful music as Gurga began rapid-fire questioning. With each correct answer, chosen from multiple choices on the screen, students gained points that could be used for avatar upgrades, privileges like listening to music in class, and a competition against other classrooms. The available characters — warriors, mages and healers — each have different powers and must collaborate to succeed.

Points are awarded for class participation as well as good behavior, but the kids can also be penalized, as was the case for one of Gurga’s seventh-graders who told a classmate to “shut up.”

A middle school in New York City, Quest to Learn, was the first public school to fully embrace game-based learning when it opened nearly a decade ago. The Manhattan school, developed by game theorists with the Institute of Play, has been closely followed since by researchers hoping for hard evidence of results from technology-inspired gamification.

In the last school year, 43 percent of Quest to Learn’s students were up to state standards on the state English test, compared to 41 percent citywide, and 29 percent of its students met state standards on the state math test, compared to 33 percent citywide. But advocates say standardized testing alone does not tell the story. Outside studies have shown growth in soft skills such as collaboration, creative thinking and empathy, according to Ross Flatt, director of programs and partnerships for the Institute of Play, a nonprofit studio that uses game design principles to develop new learning experiences.

To help educators identify programs with promise, the Johns Hopkins University Center for Research and Reform in Education launched a website that rates math and learning programs based on how they meet evidence standards for effectiveness under federal education law. The center’s director, Robert Slavin, said there are some programs that have shown positive impacts but on average improvements are small.

“When people talk about technology transforming everything, it may in the future, but it’s not there yet,” Slavin said.

Some question whether the graphics, videos and sounds in so many programs are doing harm by teaching students to pursue the rewards.

“Part of life is figuring out how to learn to love things and how to persevere in things even when it’s not extrinsically motivated,” said Christopher Devers, an education researcher at Johns Hopkins who said his review of the evidence suggests that on balance, games-based approaches tend to influence students in negative ways.

One of the better known programs, DreamBox, teaches math by offering a series of problems that can grow increasingly challenging as the student enters correct answers. The program, which began as an app for consumers, entered the school market in 2011 and last year had 2.6 million student users. The company charges a fee of $7,500 per school building per year.

DreamBox CEO Jessie Woolley-Wilson said the program is intended as an aid for teachers who can’t be expected to personalize learning for two dozen students simultaneously.

“Let’s figure out a way to support a way to deliver the best teaching, and allow the learning guardian to get back to art of teaching,” she said. “Technology can deliver that math personalization in a way that can give the learning guardian actionable insights.”

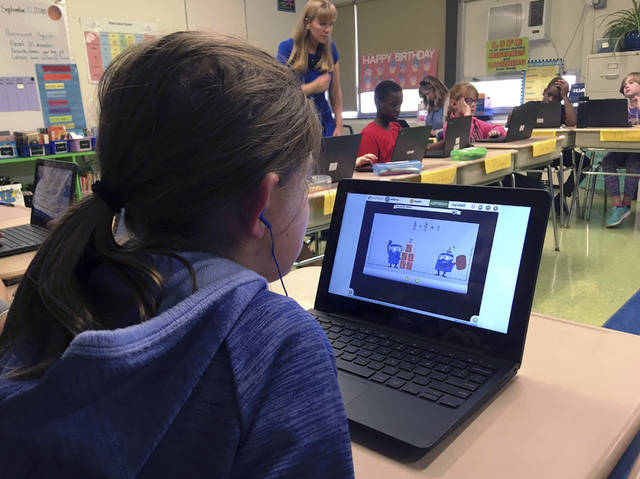

In Groton, Connecticut, early users of DreamBox reported anecdotal evidence of improved outcomes and schools are now using it district-wide. In Heather Dalton’s fifth-grade classroom at the Charles Barnum Elementary School, students spent the first half of a recent class working individually on DreamBox with headphones on. Information about their level of mastery of fractions was sent to Dalton’s laptop, but the students were most excited about the short video-game rewards they received between levels and the coins they gathered for upgrades to their avatars.

“There’s a lot of learning,” Dalton said, “but it feels like a game to the kids.”