Beginners take heart: Indigo dyeing makes everyone look good

When the outcome of a craft project is a surprise, it’s often not a good surprise. My recent experience trying indigo dyeing in Tokyo was an exception to that rule.

When the outcome of a craft project is a surprise, it’s often not a good surprise. My recent experience trying indigo dyeing in Tokyo was an exception to that rule.

Dye from the indigo plant has been used for centuries all over the world. It’s the familiar blue of blue jeans, and in a class at the Wanariya workshop in Tokyo, the technique we used was also familiar: A simple version of the craft called shibori, it reminded me of tie-dyeing in school art classes long ago.

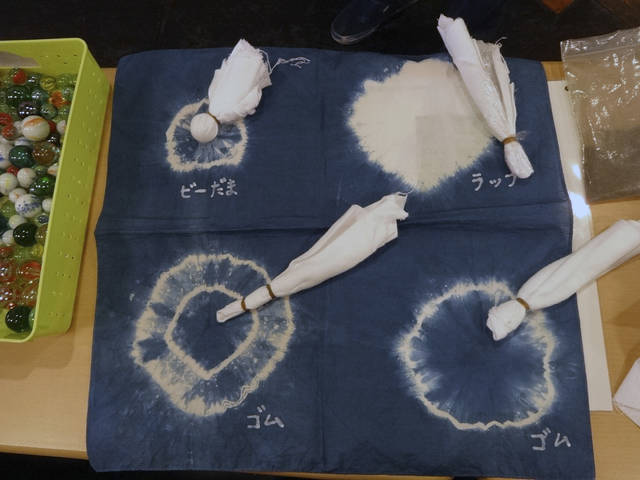

Using some scraps as examples, the teacher first explained how to wrap the fabric around marbles with rubber bands, or twist bits of it up with rubber bands, depending on the pattern we wanted. He also showed us a couple of folding techniques, but to me these screamed “not for beginners,” so I stuck with the rubber bands and marbles.

We were each given a lovely indigo-dyed apron to cover our clothes, and two pairs of rubber gloves to wear on top of each other. The reason for the latter was obvious: The instructor’s blue-stained fingers looked like they probably never come completely clean.

He warned us that the vat of dye would smell strong. It wasn’t pleasant, but not awful either. Just as striking was the look of it — this wasn’t just a tub of colored liquid. The surface was covered with froth, with a big bubble in the middle that he said was called “the flower of indigo.”

The instructor soaked my piece of fabric in plain water first so it would take up the dye better. Then he told me to dunk it in the vat and knead it “for as long as I say.”

That’s where the process gets complicated. After kneading, you lift the item out of the dye and hold it in the air for a few moments, while the color changes from a sort of dull brown to blue, as oxidation takes place. Then you dunk and knead it again — and possibly again. The duration and number of dips is how dyers get so many shades of blue — traditionally there are 48 — out of the same pot of dye.

Rinsing was left to a small washing machine. When the other two people in the class unwrapped their items, all three of us gasped at how beautiful they were. I assumed they had some talent that I lacked, but when I unwrapped mine, we all exclaimed the same way.

No doubt to a real artisan, the results looked like they’d been made by children, but I’ve never done a craft where the first attempt was so surprising and satisfying.

Indigo dyeing is complex and unlike other natural dyes. It’s not easy to get indigo to dye fabric, which is why it’s good for tie-dying: A rubber band is enough to stop it.

Most dyes are soluble in water, but not indigo, says Catharine Ellis, textile artist and co-author of a forthcoming book on natural dyes. “Even if it’s a fine powder, you stir it up and you just have fine particles in the water,” she says. To make the indigo soluble takes “magic and chemistry.”

The Japanese method involves composting the indigo leaves. Then, creating and tending the dye vat sounds something like caring for a sourdough starter. There’s talk about “feeding” and keeping it “healthy,” like it’s a living thing.

Indigo needs an alkaline environment, which is achieved by using substances like wood ash lye. Then, natural materials are added: Ellis may use sugar or henna; the Japanese use plant material or sake.

“What happens is what’s called a reduction,” Ellis says. “During the fermentation and reduction, the oxygen molecule that is bound to the indigo very strongly become less strongly bound, so the indigo can become soluble in water.”

As the natural materials break down, conditions become more acidic, so you have to keep “feeding” the vat.

“All that froth on the top, you learn how to read it — the size of the bubble, the color of the bubbles,” Ellis says. “You take the pH, you do dye tests with it, you just have to observe.”

Indigo and cotton have a special relationship, sticking to each other “like no other dyes and fibers,” says Teresa Duryea Wong , author of “Cotton and Indigo from Japan” (Schiffer, 2017).

Most people think of silk when they think of Japanese textiles. But Wong says cotton holds a special place as well.

“Raising cotton in Japan started about 600 years ago and it changed everything,” she says. Back then, when the nobility controlled all aspects of everyday life, peasants could grow cotton on the edges of their fields and experiment with it, since it was unregulated.

Indigo-dyed cotton was first used for farmers’ clothes and fisherman’s and fireman’s jackets. Gradually it became more decorative, eventually growing into an art form.

There is a synthetic version of indigo. It still has to go through the reduction process since it’s chemically identical to the real thing, but it’s less expensive, so the natural dye has become much less common.

“In Japan, there were about 40,000 acres of farms growing indigo at the beginning of the 1900s, and making the indigo dyestuff,” says Wong. “Today it’s estimated to be less than a hundred.”

The craft itself, though, seems to be doing fine. In her research, Wong saw many trendy uses of indigo-dyed fabric. One is based on the traditional yukata — a sort of light cotton kimono-like robe worn to summer festivals and after a bath: “There’s a high-fashion spin on that, with hand-dyed indigo and wearing it with jeans and boots.”

Modern uses are not confined to high fashion, though. The Wanariya shop, like many others, dyes T-shirts, sneakers, baseball caps and tote bags.