News and notes about science

Vesuvius turned one victim’s brain to glass

Five years ago, Italian researchers published a study on the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in the year 79 that detailed how one victim of the blast, a male presumed to be in his mid-20s, had been found nearby in the seaside settlement of Herculaneum. He was lying face down and buried by ash on a wooden bed in the College of the Augustales, a public building dedicated to the worship of Emperor Augustus.

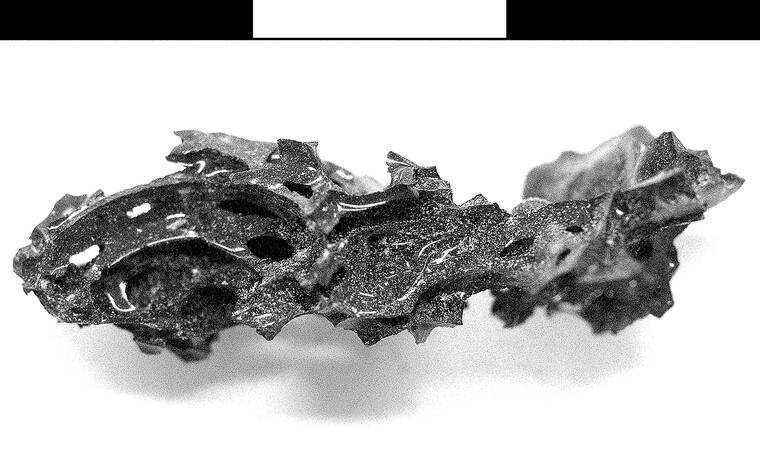

In 2018, a researcher discovered black, glossy shards embedded inside the man’s skull. A 2020 paper speculated that the heat of the explosion was so immense that it had fused the victim’s brain tissue into glass. Forensic analysis revealed proteins common in brain tissue and fatty acids found in human hair, while a chunk of charred wood unearthed near the skeleton indicated a thermal reading as high as 968 degrees Fahrenheit. It was the only known instance of soft tissue — much less any organic material — being naturally preserved as glass.

Now, a paper published in Nature has verified that the fragments are indeed glassified brain. Using techniques such as electron microscopy, energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy and differential scanning calorimetry, scientists examined the physical properties of samples taken from the glassy fragments and demonstrated how they were formed and preserved.

Orange alert: What caused the colors on this snowy owl?

Bill Diller, a photographer living in Huron County, Michigan, had never seen a snowy owl quite like this.

In January, Diller’s neighbor told him about a “red-spotted snowy owl” in the area. It’s a part of Michigan known as the Thumb, which becomes home to many snowy owls in the winter.

People were calling the bird Rusty.

“I had never heard of such a thing,” Diller said, “so I figured either he didn’t know what he was talking about or this was some kind of exotic bird from Asia.”

When he soon shared pictures on Facebook of the eye-catchingly orange bird perched atop a utility pole, he helped create a feathered phenomenon. The discovery has perplexed avian experts, too, creating an enduring mystery about what might have made a white bird turn bright orange.

Julie Maggert, a snowy owl enthusiast, heard of Diller’s sighting and became determined to see Creamsicle, as she nicknamed the bird. She made a series of visits over several days from her home in central Michigan with her Nikon Z8 and a zoom lens. After hours of waiting at a respectful distance, she finally got the perfect shot of the tinted bird on a telephone pole.

Her pictures helped make the case undeniable: The bird shared a color scheme with the planet Jupiter or a clownfish. But why?

Scientists who have studied owls for years struggled to explain the bird’s curious plumage.

Kevin McGraw, a bird coloration expert and biologist at Michigan State University, shared a surprising hypothesis: The owl became orange as a result of a genetic mutation driven by environmental stress, such as exposure to pollution.

McGraw said in an email interview that samples from the bird were needed to test that and other hypotheses.

Geoffrey Hill, an ornithologist at Auburn University and co-author with McGraw of a book about bird coloration, shared his interpretation.

“It seems unlikely that it has spontaneously produced red pigmentation via a genetic mutation,” Hill said.

Saturn gains 128 new moons, bringing its total to 274

Astronomers say they have discovered more than 100 new moons around Saturn, possibly the result of cosmic smashups that left debris in the planet’s orbit as recently as 100 million years ago.

The gas giant planets of our solar system have many moons, which are defined as objects that orbit around planets or other bodies that are not stars. Jupiter has 95 moons, Uranus has 28 and Neptune has 16. The 128 in the latest haul around Saturn bring its total to 274.

“It’s the largest batch of new moons,” said Mike Alexandersen at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, an author of a paper announcing the discovery that will be published in Research Notes of the American Astronomical Society.

Many of these moons are rocks only a few miles across — small compared with our moon, which is 2,159 miles across. But as long as the rocks have trackable orbits around their parent body, the scientists who catalog objects in the solar system consider them to be moons. That is the responsibility of the International Astronomical Union, which ratified the 128 new moons of Saturn.

The forthcoming paper’s lead author, Edward Ashton of the Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics in Taiwan, will have naming rights for the objects. The moons were discovered in 2023 using the Canada France Hawaii Telescope at Mauna Kea in Hawaii.

© 2025 The New York Times Company