‘Just weird’: Rash of injuries hits women’s college hoops

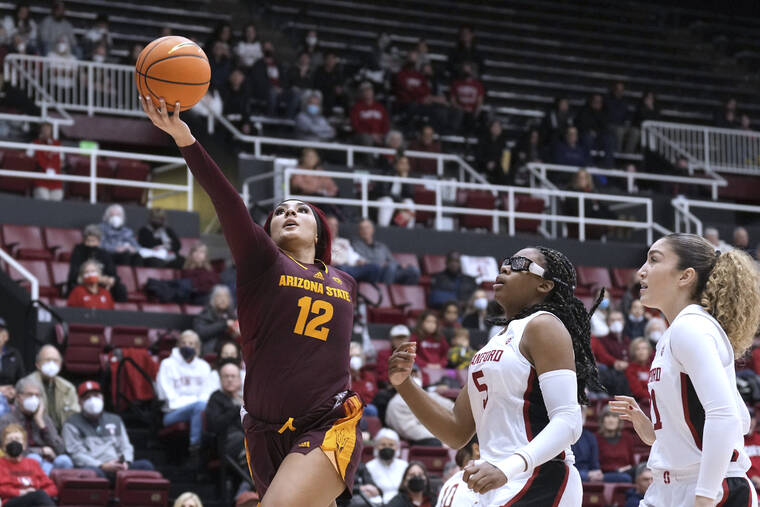

Arizona State guard Treasure Hunt (12) shoots against Stanford forward Francesca Belibi (5) and forward Brooke Demetre, right, during the first half of an NCAA college basketball game Saturday, Dec. 31, 2022, in Stanford, Calif. (AP Photo/Darren Yamashita)

UConn’s Paige Bueckers, second from left, talks with teammate Azzi Fudd in the second half of an NCAA college basketball game, Sunday, in Hartford, Conn. Fudd left the game in the first half with an injury to her knee and did not return. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

HARTFORD, Conn. — UConn star Azzi Fudd was battling for rebounding position in the first half Sunday when she banged knees with Georgetown’s Ariel Jenkins. Fudd left the game and did not return.

HARTFORD, Conn. — UConn star Azzi Fudd was battling for rebounding position in the first half Sunday when she banged knees with Georgetown’s Ariel Jenkins. Fudd left the game and did not return.

It was just her second game back after missing eight games with an injury to the same right knee. It also came a week after injuries forced the fifth-ranked Huskies to postpone a game with DePaul because it did not have enough healthy players available — a step that became sadly familiar during the height of the pandemic but is rarely seen otherwise.

A few days later, Arizona State was forced to forfeit games against Utah and Colorado because the Sun Devils had too many injured players.

Programs such as Vanderbilt also have lost multiple starters to the injury report. Low roster numbers because of health issues led Lewis and Clark Community College in Illinois to cancel the remainder of its season just this week.

With injuries mounting in women’s programs, experts note there are number of factors in play, including the specialization of sports at a younger age, and longer recovery times contributing to those thin benches. Certain knee injuries are more common in female athletes then men.

Whatever the reasons, the search for solutions is always on.

At UConn, just two players have been available for every game. Coaches have burned sage in the locker room, brought holy water to practice and had Native American dancers perform healing rituals.

Former national player of the year Paige Bueckers, who missed most of 2021-22 with a knee injury, and freshman Ice Brady both suffered serious knee injuries in the preseason. Two other players are sidelined with concussions. Other players have missed time with foot and hand injuries.

“What kind of exercises do you do in the weight room to make sure you don’t get a concussion?” coach Geno Auriemma said. “There’s nothing, you know. What do you do to make sure that your teammate doesn’t push a kid into you, a teammate knocks you on on the ground and you hit your head or where you catch your thumb and a kid shirt and break your thumb in the first first game of the year? So some of these are just weird.”

Some injuries, sports medicine experts say, may be linked to the way elite athletes are preparing for college.

Nicole Alexander, the head trainer for the WNBA’s Connecticut Sun and a former trainer at Notre Dame and North Carolina, said kids are specializing in one sport earlier and playing that sport year-round.

“So, they’re not getting a chance to rest their bodies,” she said. “You’re putting the same amount of mileage on the same body parts, over and over again. So, now you get these kids who are in college, but their bodies are such that it’s almost like they’ve been playing professional ball for 10 years because that’s all they’ve been doing.

Fudd missed two months last year with a foot injury. She also suffered ACL and MCL tears while in high school.

UCLA coach Cori Close has another theory. She said she thinks the apparent rise in injuries, especially knee injuries, can be linked to the pandemic.

“I definitely think because of COVID — the interruptions of prehab and training and periodization and off times and prevention work,” she said. “I talked to Geno about this at UConn and several other coaches. And we think it’s a dramatic effect for how the training regimens were interrupted from COVID.”

Dr. Andrew Cosgarea, an orthopedic surgeon and sports injury specialist at John’s Hopkins, said there is no data yet suggesting there are more injuries this year than in previous seasons. He said schools have been doing a lot of work teaching kids how to prevent ACL and other injuries by changing, for example, the way they cut, jump and land.

Cosgarea and other experts said one factor in the lack of available players is that athletes are sitting out longer because it leads to better outcomes when they return.

Dr. Anthony Alessi, UConn’s team neurologist, declined to talk about specific players he’s treated, but said the time it takes to return varies with each individual, but on average is now between 10 days and two weeks.

“It’s multi-factorial,” he said. “But, what we’ve found is that by making the investment in time, by gradually bringing them back to their full capacity based on their symptoms, you’ll get them at full strength to the end of the season.”

At top-ranked South Carolina, coach Dawn Staley said she’s not going to overrule the recommendation of her trainer just to get a player back sooner.

“He’s not going to tell me when to put the 2-3 (zone) out there or when to do a triangle and two. I don’t interfere in his business so that our players are ready to rock and roll. I’m going to listen,” she said.

Stanford coach Tara VanDerveer said coaches have to take some of the responsibility for not having enough healthy players to put a full team on the court.

“Women’s basketball has 15 scholarships,” she said. “I think it’s a challenge sometimes but it’s your responsibility as coaches to have a full roster. It’s challenging when you have a new coach and the (transfer) portal and people leave and stuff but part of it also is keeping people healthy. That’s a big part of the job.”

Auriemma said coaches have already cut back on the length, number and intensity of practices on the advice of medical staff, sometimes to the detriment of play. He said he is learning to be more patient when it comes to injuries.

UConn guard Nika Mühl, who missed time last year with a concussion, said that’s the hardest part for everyone involved.

“We see everybody playing every day you just want to get out there already but you have to go through the protocol,” she said.

AP Sports Writers Peter Iacobelli and Joe Reedy contributed to this story.