SAN JOSE, Calif. — A mysterious lineage of the COVID-19 virus — containing a large and startling collection of mutations — has appeared in California’s wastewater system, proof that the fast-moving pathogen is continuing to test new survival strategies.

Oddly, the virus has been found only in poop, not people. First detected in an undisclosed community by UC Berkeley scientists, it has shown no signs of causing illness. It’s led to no new outbreaks.

So where is it coming from? And should we worry about it? No one knows for sure.

But its troubling constellation of genetic changes, similar to those seen in the omicron variant, might make it more transmissible or evasive.

Here’s what else is weird: Very similar “cryptic lineages” — viral fragments with novel patterns of mutations — have been found in the sewage of other cities, such as New York City and St. Louis, Missouri. These findings were published in the journal Nature Communications on Thursday. Similar discoveries, not yet published, have reportedly been made in other U.S. cities.

So far, the California lineage has only appeared sporadically. And it’s been found in just one of the nine different city and county wastewater sites screened by UCB scientists, who would not disclose the specific locations.

“We saw it appear and then disappear, and then appear and then disappear” beginning last November, said microbial ecologist Rose Kantor, assistant research engineer and project manager, who first detected it. “So we expect we’ll probably see it again in the future.”

One theory is that it’s incubating in someone with a weak immune system who is confined to a care facility. Perhaps this person has Long COVID and has been unable to fend off the infection — so the virus persists in their body for months, mutating as it multiplies.

Another theory is that it comes from virus-infected animals, such as rats, cats and dogs. Animal poop seeps into our urban sewer systems. Like us, they get COVID-19; their immune systems also force the virus to adapt. There’s concern that a mutated animal virus could jump back into people.

None of these likely suspects would have flown between California, St. Louis and New York City. So the similar strains emerged independently at the different places; they’re not connected.

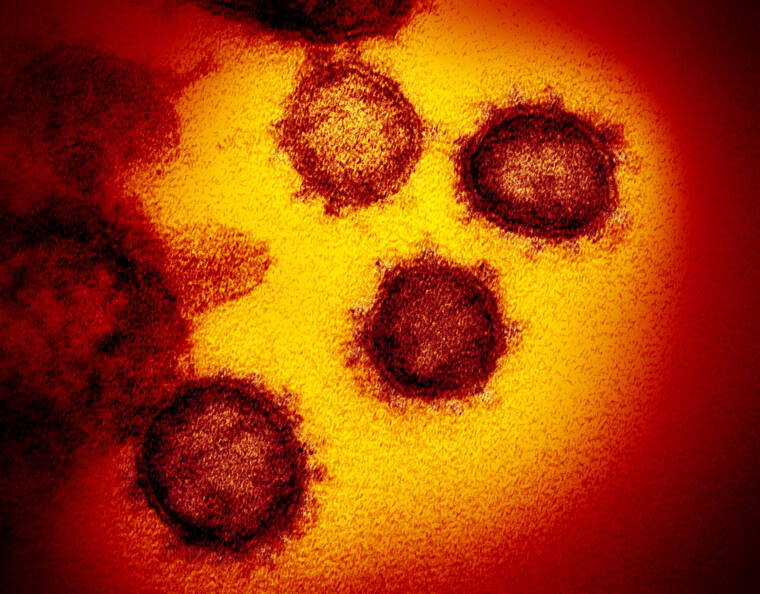

The new lineages appeared before omicron, but are similar to omicron, with 12 to 16 unusual mutations in the gene for the spike protein that studs the viral surface, and allows it to latch on to cells.

UC Berkeley’s wastewater screening project is a leader in the nation’s search for the COVID-19 virus in our poop.

Its reports, submitted to the state’s Department of Public Health, can reveal hidden outbreaks of disease. They also provide an efficient way to track the pandemic’s ebbs and flows over time — especially in communities without easy access to routine testing, where some infected residents may never feel sick so don’t take a test.

It was through wastewater surveillance, not testing, that scientists last December detected the arrival of omicron in the northern part of Santa Clara County. The variant has since gone on to sweep the nation.

Nationwide, an estimated 400 communities test the contents in sewage pipes and wastewater treatment plants. An additional 250 sites are expected to join in the next several weeks, according to Amy Kirby of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Wastewater Surveillance System.

The CDC will use this surveillance data to inform important public health decisions, such as where to set up mobile testing and vaccination sites.

“Wastewater surveillance serves as an early warning system for the emergence of COVID-19 in a community,” said Kirby at a Friday morning media briefing. Many programs conduct genetic sequencing of the virus.

But researchers at UC Berkeley, St. Louis and New York City used a unique method that can pick up linked mutations in the sewage. That’s how they discovered that their “cryptic lineages” were so similar, sharing a set of mutations.

“What’s interesting is that it’s part of this larger pattern that has been seen in other places,” said Kantor. “It’s something that we should be on the lookout for.”

Contrary to our initial understanding, the COVID-19 virus is a skilled shape-shifter. Seeking to thrive, it undergoes mutations and evolves new characteristics.

As it spreads across the world, the virus generates genetic diversity — “not only in humans but other animals,” said Jeremy Kamil, a virologist at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center Shreveport, who studies variant mutations. As it multiplies, that diversity “may not show up in the genomic surveillance data from humans, but we’re seeing it in sewers.”

The same evolutionary pressures that forced a genetic change in virus found in California could have led to similar changes to viruses in New York, Missouri and other far-flung places, he said. Evolutionary biologists call that phenomenon “convergence,” and it is common. For example, insects, birds and bats all independently evolved the ability to fly.

“Evolution is all about extremely unlikely things being disproportionately rewarded,” he said.

“At some point, we may vaccinate everyone and get everyone safe — and there may be a new variant that pops up,” he said. “It’s a haunting lottery that’s happening right under our noses.”

The CDC’s National Wastewater Surveillance System can be found at https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/surveillance/wastewater-surveillance/wastewater-surveillance.html.