Hospitals across the U.S. are feeling the wrath of the omicron variant and getting thrown into disarray that is different from earlier COVID-19 surges.

This time, they are dealing with serious staff shortages because so many health care workers are getting sick with the fast-spreading variant. People are showing up at emergency rooms in large numbers in hopes of getting tested for COVID-19, putting more strain on the system. And a surprising share of patients — two-thirds in some places — are testing positive while in the hospital for other reasons.

At the same time, hospitals say the patients aren’t as sick as those who came in during the last surge. Intensive care units aren’t as full, and ventilators aren’t needed as much as they were before.

The pressures are nevertheless prompting hospitals to scale back non-emergency surgeries and close wards, while National Guard troops have been sent in several states to help at medical centers and testing sites.

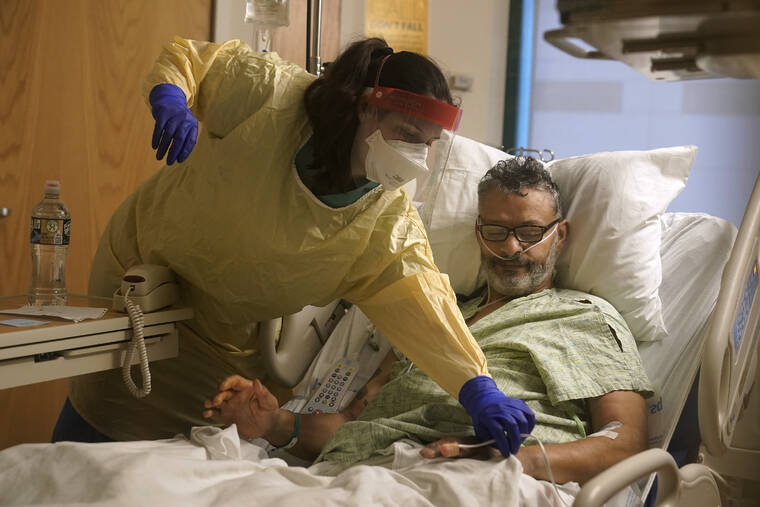

Nearly two years into the pandemic, frustration and exhaustion are running high among health care workers.

“This is getting very tiring, and I’m being very polite in saying that,” said Dr. Robert Glasgow of University of Utah Health, which has hundreds of workers out sick or in isolation.

About 85,000 Americans are in the hospital with COVID-19, just short of the delta-surge peak of about 94,000 in early September, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The all-time high during the pandemic was about 125,000 in January of last year.

But the hospitalization numbers do not tell the whole story. Some cases in the official count involve COVID-19 infections that weren’t what put the patients in the hospital in the first place.

Dr. Fritz François, chief of hospital operations at NYU Langone Health in New York City, said about 65% of patients admitted to that system with COVID-19 recently were primarily hospitalized for something else and were incidentally found to have the virus.

At two large Seattle hospitals over the past two weeks, three-quarters of the 64 patients testing positive for the coronavirus were admitted with a primary diagnosis other than COVID-19.

Joanne Spetz, associate director of research at the Healthforce Center at the University of California, San Francisco, said the rising number of cases like that is both good and bad.

The lack of symptoms shows vaccines, boosters and natural immunity from prior infections are working, she said. The bad news is that the numbers mean the coronavirus is spreading rapidly, and some percentage of those people will wind up needing hospitalization.

This week, 36% of California hospitals reported critical staffing shortages. And 40% are expecting such shortages.

Some hospitals are reporting as much as one quarter of their staff out for virus-related reasons, said Kiyomi Burchill, the California Hospital Association’s vice president for policy and leader on pandemic matters.

In response, hospitals are turning to temporary staffing agencies or transferring patients out.

University of Utah Health plans to keep more than 50 beds open because it doesn’t have enough nurses. It is also rescheduling surgeries that aren’t urgent. In Florida, a hospital temporarily closed its maternity ward because of staff shortages.

In Alabama, where most of the population is unvaccinated, UAB Health in Birmingham put out an urgent request for people to go elsewhere for COVID-19 tests or minor symptoms and stay home for all but true emergencies. Treatment rooms were so crowded that some patients had to be evaluated in hallways and closets.

Doctors and nurses are complaining about burnout and a sense their neighbors are no longer treating the pandemic as a crisis, despite day after day of record COVID-19 cases.

“In the past, we didn’t have the vaccine, so it was us all hands together, all the support. But that support has kind of dwindled from the community, and people seem to be moving on without us,” said Rachel Chamberlin, a nurse at New Hampshire’s Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center.