Nebraska-Oklahoma provided stage for Black stars in ’70s

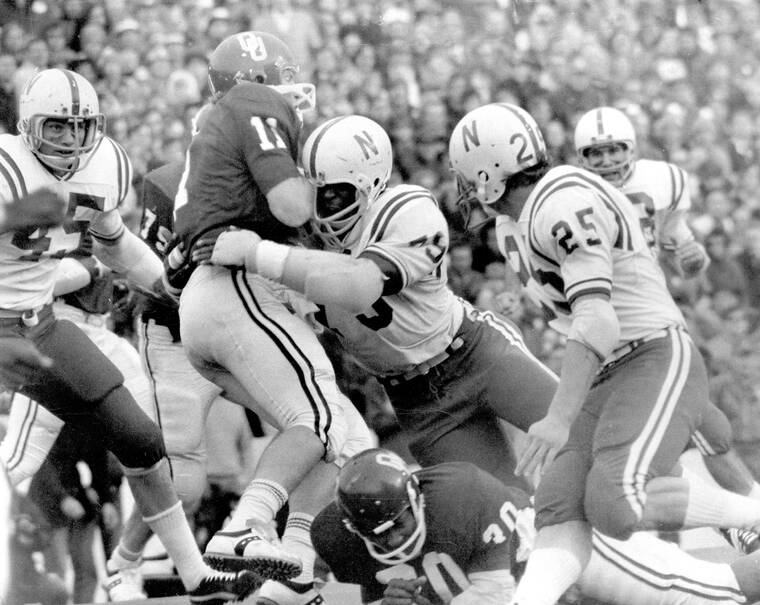

FILE - In this Nov. 25, 1971, file photo, Nebraska's Rich Glover (79) brings down Oklahoma quarterback Jack Mildren (11) as Nebraska defenders Bob Terrio (45) and Dave Mason (25) close in during a college football game in Norman, Okla., on Thanksgiving Day. The game on Thanksgiving 50 years ago is back in the spotlight as Nebraska and Oklahoma renew their rivalry on Saturday, Sept. 18, 2021. (Lincoln Journal Star via AP, File)

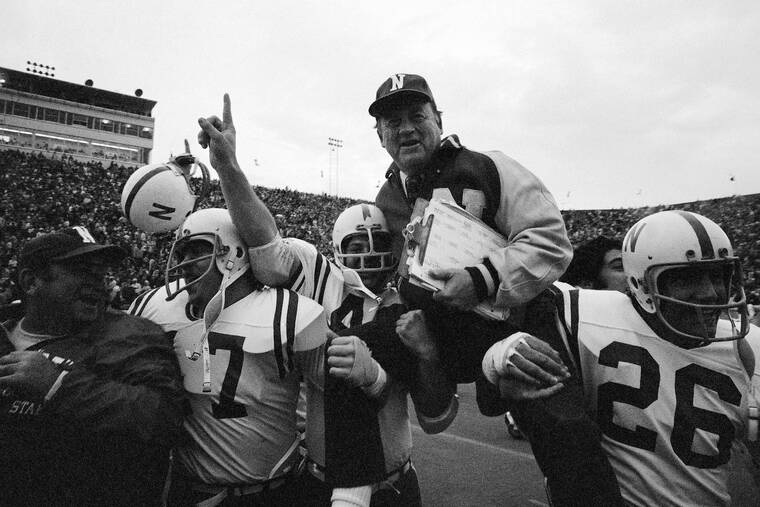

In this Nov. 25, 1971, file photo, Nebraska head coach Bob Devaney is carried off the field by his victorious players after they defeated Oklahoma 35-31 in an NCAA college football game in Norman, Okla., on Thanksgiving Day. The game on Thanksgiving 50 years ago is back in the spotlight as Nebraska and Oklahoma renew their rivalry on Saturday. (AP Photo/File)

In this Nov. 25, 1971, file photo, Nebraska’s Johnny Rodgers (20) celebrates in the end zone after his long punt return against Oklahoma in Norman, Okla., on Thanksgiving Day. The game on Thanksgiving 50 years ago is back in the spotlight as Nebraska and Oklahoma renew their rivalry on Saturday. (Lincoln Journal Star/AP, File)

FILE - In this Nov. 25, 1971, file photo, Nebraska’s Johnny Rodgers (20) hugs an assistant coach on the sideline after his punt return for a touchdown against Oklahoma in the first quarter of college football game in Norman, Okla., on Thanksgiving Day. The game on Thanksgiving 50 years ago is back in the spotlight as Nebraska and Oklahoma renew their rivalry on Saturday, Sept. 18, 2021. (Lincoln Journal Star via AP, File)

NORMAN, Okla. — Half a century ago, the Nebraska-Oklahoma rivalry games offered a grand stage for the best Black college football players while the South dragged its feet on integration.

NORMAN, Okla. — Half a century ago, the Nebraska-Oklahoma rivalry games offered a grand stage for the best Black college football players while the South dragged its feet on integration.

With Nebraska’s Johnny Rodgers, Rich Glover and Willie Harper and Oklahoma’s Greg Pruitt, Joe Washington, Rod Shoate and brothers Lee Roy, Lucious and Dewey Selmon leading the way, the programs dominated with stars most schools in the South wouldn’t even recruit.

After Texas became the last all-white team to win a national title in 1969, Nebraska and Oklahoma won two Associated Press national titles each between 1970 and 1975, with Black athletes playing critical roles. Each won their annual November showdown against each other on the way to those championships.

Rodgers, Pruitt and Glover were among the biggest stars in the “Game of the Century” — No. 1 Nebraska’s win 35-31 win over No. 2 Oklahoma in 1971. They placed 1-2-3 in the 1972 Heisman race (Rodgers, Pruitt, Glover) — the first time that happened for Black players.

“I think that our play and our success on those football teams opened the door for a lot of Black kids that followed us,” Pruitt recalled amid preparations for Nebraska’s game at Oklahoma this weekend, 40 years after their famous showdown.

The honors and recognition streamed in for Black athletes at Nebraska and Oklahoma in those days. Glover won the Outland and Lombardi Trophies in 1972 and Lee Roy Selmon won both in 1975. Washington, an electrifying running back known for his silver shoes, finished third in the Heisman voting in 1974.

It goes back to the coaches who decided to prioritize recruiting Black athletes — Chuck Fairbanks and Barry Switzer at Oklahoma and Bob Devaney and Tom Osborne at Nebraska.

“Before it happened, if I was to pick the schools most likely to break the barriers, Oklahoma and Nebraska probably would not have made the list,” said Richard Lapchick, head of the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport at the University of Central Florida. “But coaches like Barry Switzer, Tom Osborne, Chuck Fairbanks and Bob Devaney were bold enough to see the future and courageous enough to bury the previous era of segregated teams. The results were evident in their records and the records of some of their great Black players.”

Switzer grew up in the 1940s and ’50s near tiny Crossett, Arkansas, and said his father, Frank, was a bootlegger. Frank had Black bootleggers working for him, and his son often tagged along when it was time to collect. Through that, Switzer saw the kids on the other side of the tracks and learned they had much in common. He said his father often helped Black people, and he committed to do the same through recruiting when he became Oklahoma’s head coach in 1973.

“It was the right thing to do,” Switzer said. “So when I became head coach, I said, ‘You need to understand that this is the way it’s going to be.’ I told my staff that’s the way we’re going to approach it, and you’re coaching for the wrong staff if you don’t want to do it my way.”

The coaches were smart to fall in line — Oklahoma had the highest winning percentage of teams that played Division I-A football throughout the 1970s and won national titles in 1974 and 1975. Nebraska was fourth and won national championships in 1970 and 1971.

Switzer established Oklahoma as a place to go for Black players in Texas, including Oklahoma’s 1978 Heisman winner, Billy Sims.

The foundations for that early 1970s dominance were set much earlier.

Prentice Gautt became Oklahoma’s first Black athlete in 1956. He was a two-time all-conference selection and the 1959 Orange Bowl MVP. Receiver Eddie Hinton was a third-team AP All-American for the Sooners in 1968.

Nebraska’s first Black All-American was offensive lineman/linebacker Bob Brown in 1963, and the Huskers fielded the “Magnificent Eight” — eight Black players on the two-deep depth chart — in 1964. Nebraska’s 1971 national championship team featured seven Black players with prominent roles.

Texas and Alabama — the old guard — were dealt stinging defeats by the Big Reds in the early 1970s.

Alabama beat Nebraska for the AP title in 1965 before falling into a drought. Crimson Tide coach Paul “Bear” Bryant wanted to recruit Black players but was met with resistance. The late Sam Cunningham, the Black USC running back who shredded Alabama in 1970, has been given much credit for helping integrate college football in the South.

Nebraska left no doubt that it was time for change when the Huskers played Alabama for the national title in the 1972 Orange Bowl. Rodgers burned the Crimson Tide with a 77-yard punt return for a touchdown in the first quarter and the Cornhuskers cruised to a 38-6 victory.

“I know people talk about how USC beat Alabama in Birmingham the year before we beat Alabama rather soundly in Miami, but I also know that our game in that Orange Bowl was a big factor that began to erode the color barriers even more in the South,” Osborne told Huskers.com.

Texas beat Oklahoma in 1970, its 12th win in 13 tries. Oklahoma, with its influx of Black talent, beat the Longhorns five straight years from 1971 to 1975.

As for the Big Eight (and later Big 12) rivalry, Oklahoma dominated Nebraska in the late ’70s and into the 1980s until the Cornhuskers beat Switzer three times with Turner Gill — a Black quarterback from Fort Worth, Texas. Both were ahead of the curve in featuring Black quarterbacks and won national titles with them — Oklahoma with Jamelle Holieway in 1985 and Nebraska with Tommie Frazier in 1994 and 1995.

“If you know your Oklahoma history and you know your Nebraska history, the platform that they gave Black athletes was amazing,” Holieway said.

AP Sports Writer Eric Olson in Omaha, Nebraska, contributed to this report.