The early morning of April 1, 1946, seemed at first to be the start of a normal Monday for residents of Hilo and surrounding villages.

The early risers, such as fishermen and sugar plantation workers, were already at work — while others prepared themselves to return to their jobs or to school after the final weekend in March.

It also was April Fools Day, but the events of 75 years ago today were no joke.

An earthquake with an estimated magnitude between 7.8 and 8.6, rocked the Aleutian Islands off Alaska. The Pacific-wide tsunami generated by the massive temblor hit the Hilo waterfront around 7 a.m. The waves — estimated by those who saw them as between 35 feet and 50 feet in height — killed 159 people and devastated the Hilo waterfront.

Twenty-five of the dead were in the Hamakua Coast village of Laupahoehoe, including teachers and students at the school, then situated on low-lying Laupahoehoe Point.

Damage from the series of waves was estimated at $26 million — the equivalent of about $350 million in 2021.

The late Robert “Steamy” Chow, a celebrated local historian, was a 24-year-old motor patrolman just arriving on his beat after the first wave hit Hilo town.

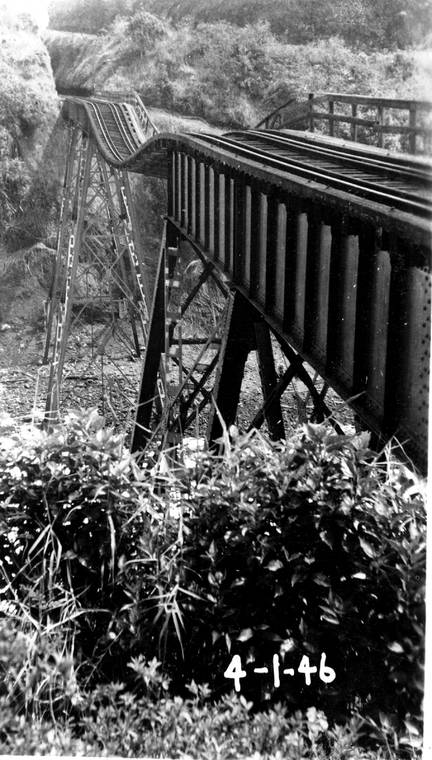

He told the Tribune-Herald in 2008 that people were yelling “tidal wave” at him, to which he replied: “Yeah, April fool.” He learned they weren’t joking as he witnessed waves covering the Wailuku River railroad bridge and buildings washed off their foundations onto Front Street — now known as Kamehameha Avenue.

“The railroad depot was completely demolished, like a bulldozer ran through it,” Chow recalled.

Taking the brunt of the destruction was the Shinmachi neighborhood, situated on the Hilo Bayfront plain that Wailoa River State Recreation Area now occupies.

Established in 1913 by a group of first-generation Japanese entrepreneurs who had left the plantation and started businesses — including Hawaii Planing Mill (HPM), I. Kitagawa Motors, Atebara Potato Chips, S. Tokunaga Store and Hilo Macaroni Factory — Shinmachi means “new town.”

Ramon Goya, now 79, is a retired University of Hawaii at Hilo athletic director and one of the founding fathers of the Vulcans intercollegiate athletic program. He was just two weeks away from his fifth birthday, a kindergartner staying home that morning in the family’s Shinmachi residence because he was ill.

“All of a sudden, my father burst into my room and got me,” Goya said last week. “He threw me over his shoulder, so I was looking backward, toward the ocean.”

He said his father, Ronald “Square” Goya, and his mother, May Toyama Goya, ran toward a flatbed truck that was next door, where a Durant-Irvine Co. building-and-supply warehouse was under construction.

“I remember distinctly as my parents were running toward the truck, I was looking back, and I saw a wall of water,” Goya said. “I don’t know how big, how tall the wall of water was, but … the water was just coming toward us. We got onto the truck, and the truck actually took us to safety.”

Goya said after he and his mom were secure on higher ground, his dad returned to the waterfront.

“I asked my mom, ‘Why is Dad getting off the truck? Why is he leaving us?’” Goya recollected. “And my mom told me that he went to find his parents, my grandmother and grandfather. Because earlier in the morning, they both went to the Goya Brothers service station, which was located at the corner of Kamehameha and Bishop.”

Goya was one of the fortunate ones who lost no family members that traumatic day in Shinmachi. Their Punahoa Street home, near where the Kamehameha statue now presides, survived because it was on slats and was far enough from the shore that the tsunami waves rushed under it.

The family service station was damaged but not demolished, because it was somewhat sheltered by HPM, which was across the street. The family repaired the service station, and May Goya opened the historic May’s Fountain inside. It became what her son described as “a ‘Happy Days’ kind of place where the kids could hang out.” And while May Goya probably didn’t invent the loco moco, she’s generally credited with the addition of a fried egg to the rice, gravy and meat dish — turning it into the Hilo-style delicacy we know today.

“Talk about resilience,” Goya said. “There’s a lot of places that took damage. I think Shinmachi reflected Hilo town, too. These people had the resiliency, the toughness, the grit to be able to withstand all the hardship they went through and go forward.”

Not all families in Shinmachi were as fortunate as the Goyas, however.

Jean Matsumoto, now 79, was 4 years old and a Shinmachi resident on the fateful day.

“I remember when the wave hit,” said Matsumoto, a retired manager at the former IEG Federal Credit Union, which has merged with HawaiiUSA FCU. “We looked out the back door, my mom, my sister and I. And we saw people on the rooftops, floating down in the water. And then, I guess, the next wave hit. When it hit us, we were washed out of the house, my little sister, myself and my mother. We all hung on to my mom, but my sister never made it.

“And then, someone came and saved us.”

The loss of Matsumoto’s 2-year-old sister, Vivian Abe, wasn’t the only death the family endured that day.

Her grandparents, Ejiro and Kura Tanaka, and Matsumoto’s infant brother, Jerry Abe, were all killed when her grandparent’s house — which was next door to her parents’ home — collapsed under the weight and force of the onrushing wall of water.

Matsumoto’s aunt, Fusae Takaki — the mother of Audrey Wilson, the Tribune-Herald’s food columnist who wasn’t yet born — also was in Matsumoto’s grandparents’ home that morning.

“She was washed out of the house. She survived,” Matsumoto said. “She didn’t know how to swim, but when she came up, somebody pulled her out, so she was saved.”

Matsumoto’s older brother, James Abe, also survived.

“My older brother was waiting for a school bus, and the wave hit him,” she said. “He was hanging to a chair and floating outside. A Boy Scout, a Mr. Valera, I remember, saw him, tied a rope around himself and went in and saved my brother.

“My father was working when the wave hit, and he ran down, and he saw my brother being pulled out by this Boy Scout.”

Matsumoto also pointed to resiliency — that of her mother, Shizue Abe.

“Now, looking back, I think of my mother as an amazing woman,” she said. “I’m also saddened she lost everything. Two children, her parents, all in the same day. And you know, she took care of us.

“Ever since then, I had a phobia about the water. I never learned how to swim until I graduated from high school. I just had to fight my fear. It was kind of traumatic for me. I remember whenever we had a tidal wave warning, I used to get upset and sick for awhile, until I grew older. Because before, we always had these alarms.”

After the 1960 tsunami that also devastated Hilo, local officials decided Shinmachi wouldn’t be rebuilt a second time.

Tonight at 9 p.m. PBS Hawaii is airing the documentary “Shinmachi: Stronger Than a Tsunami” featuring stories told by former residents of the neighborhood and narrated by Akiko Masuda, the Hakalau innkeeper. It also will air at 8 p.m. Saturday, April 24.

Email John Burnett at jburnett@hawaiitribune-herald.com.