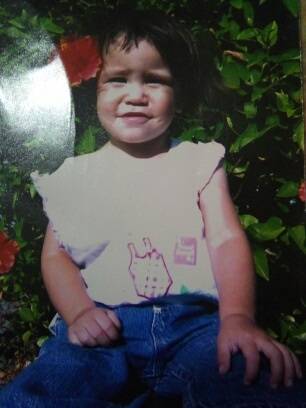

A 37-year-old Hilo woman was sentenced Monday to 10 years of probation for her role in starving her 9-year-old daughter to death in 2016.

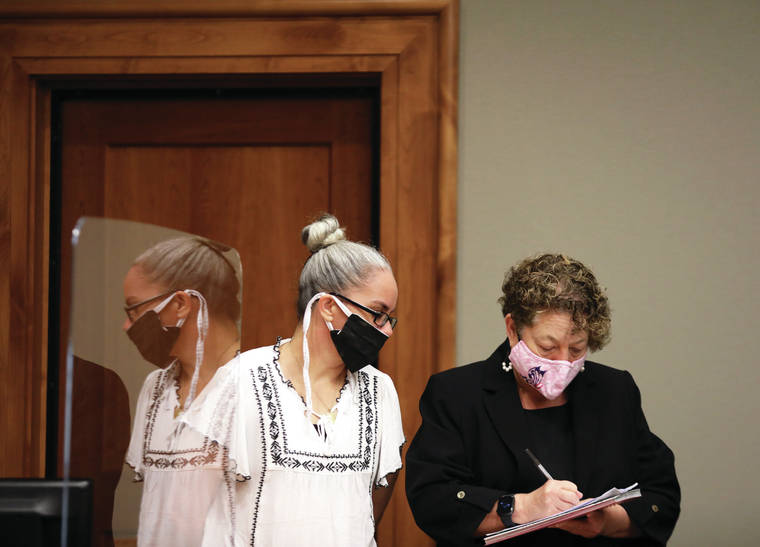

Tiffany Stone faced a possible 20 years in prison when she was sentenced by Hilo Circuit Judge Henry Nakamoto.

Stone, who originally was charged with second-degree murder for the June 28, 2016, death of Shaelynn Lehano-Stone, pleaded no contest to manslaughter in December.

Stone will serve no further jail time because she has spent almost 4 1/2 years in pretrial custody — more than twice the maximum two-year jail term in a probation sentence.

Kevin Lehano, Stone’s 53-year-old husband, and Henrietta Stone, Stone’s 63-year-old mother, are charged with second-degree murder in the death of the developmentally-disabled child. They each remain in custody in lieu of $100,000 bail.

Lehano, who pleaded not guilty and has been found fit to stand trial, has a hearing April 9 for “further proceedings” in his case. Henrietta Stone is undergoing a court-ordered mental examination and has a hearing scheduled for April 30.

The child had been pulled out of Hilo Union Elementary School by Henrietta Stone, the legal guardian, to be home-schooled. A call to 911 by Lehano brought first responders to Henrietta Stone’s apartment directly across from Hilo’s central fire station on Kinoole Street on June 28, 2016.

There, they found the unconscious and unresponsive girl, who died later that day.

The child had been on Child Welfare Services radar since birth and was in foster care four times before her grandmother was awarded custody. Her two siblings, who also were in the CWS system, are now in adoptive homes.

Deputy Prosecutor Suzanna Tiapula asked the judge Monday to sentence Tiffany Stone to the maximum 20 years in prison. She painted Stone as a liar and manipulator who “takes no responsibility for the death of her daughter” and blamed everyone else, including CWS, her mother and her husband, for her situation.

“This defendant chose to do nothing, and her daughter died,” Tiapula said. “… When her liver and kidneys stopped working, she couldn’t control her urination or defecation. As her organs were shutting down, the family referenced that she was, quote, pissing herself. The defendant watched while her daughter starved. She didn’t feed her child in a house with three refrigerators, all of which had food in them.

“And on the day her daughter lay down, never to get up again, this defendant saw her daughter lying on the floor in her own filth — and walked away.”

Melody Parker, Stone’s court-appointed attorney, argued for probation.

“Miss Stone stands before this court not because she intentionally desired the death of her child,” Parker said. “Not because she ever wanted — whatever her actions were or were not — to end up with that result. She is here because she attended a Family Court hearing where the judge gave the child to the maternal grandmother and advised that she stays there until grandma dies or (the child) turns 18.”

According to Parker, many who handled the child’s case came up short in performing their duties.

“I would point out to the court that many, many, many people saw this child who had a duty to report,” she said. “… Tiffany Stone loves her children. That’s the one thing, dealing with her in the four years that she’s been in custody, I have been able to determine more than anything else. And she accepted this plea because she recklessly disregarded a risk that society felt that she should have been able not only to perceive, but to change.

“And given the situation she was in, that is where she took responsibility.”

Asked by Nakamoto if she wished to address the court, Stone declined.

“It is clear that maybe not your conduct, but your inaction contributed to the death of your child,” the judge told Stone. “In this case, as is stated, you’ve gone through the Child Welfare Services (and) numerous court proceedings since the birth of your child. It’s clear, though, you have had and still have serious mental issues, and issues caring for your children and, especially your child who did pass away, had issues also.

“I understand the legality of how the Family Court process works and understand that you did not have control over a lot of the things that went on. But you did have control of whether or not or how aggressively you called for help.

“That’s why I think this sentence is appropriate.”