Biden taking ‘creative steps’ to push for $1.9T aid plan

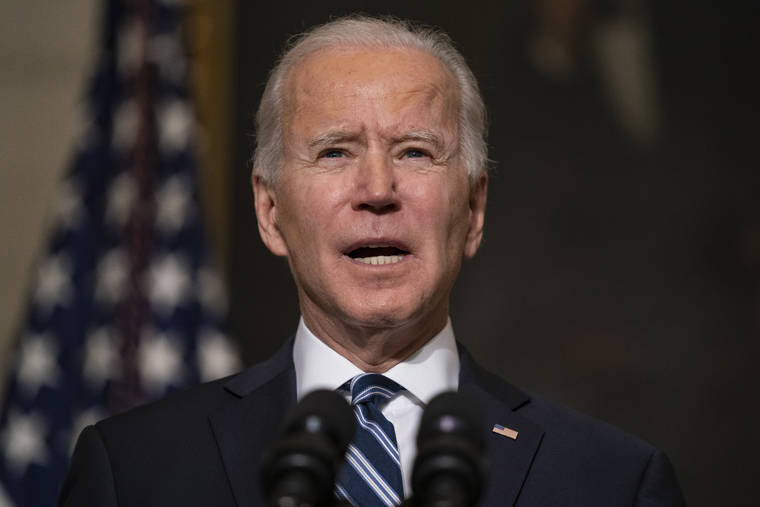

In this Jan. 27, 2021, photo, President Joe Biden speaks in the State Dining Room of the White House in Washington. Biden’s $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief package presents a first political test. More than a sweeping rescue plan, it's a test of the strength of his new administration, of Democratic control of Congress and of the role of Republicans in a post-Trump political landscape. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

WASHINGTON — The Biden administration said on Friday it’s taking “creative steps” to get broader public support for its $1.9 trillion COVID-19 rescue plan, as attempts to strike a deal with Republicans have led to concerns about delays in coronavirus relief and Senate Democrats prepared to pass the measure along party lines.

WASHINGTON — The Biden administration said on Friday it’s taking “creative steps” to get broader public support for its $1.9 trillion COVID-19 rescue plan, as attempts to strike a deal with Republicans have led to concerns about delays in coronavirus relief and Senate Democrats prepared to pass the measure along party lines.

White House press secretary Jen Psaki said President Joe Biden fully recognizes the importance of speaking directly to the American people about his plan for vaccinations and supporting the economy, but the pandemic has limited his ability to safely travel the country to drum up support. That has left the administration relying on TV interviews with local media and outreach to governors and local officials as well as to progressive and civic groups.

“We’re taking a number of creative steps, a little outside of the box,” Psaki said. “Certainly, his preference would be to get on a plane and fly around the country.”

Despite Biden’s calls for unity, Democrats said the stubbornly high unemployment numbers and battered U.S. economy leave them unwilling to waste time courting Republican support that might not materialize. They also don’t want to curb the size and scope of a package that they say will provide desperately needed money to distribute the vaccine, reopen schools and send cash to American households and businesses.

The standoff over Biden’s first legislative priority is turning the new rescue plan into a political test — of his new administration, of Democratic control of Congress and of the role of Republicans in a post-Trump political landscape.

Success would give Biden a signature accomplishment in his first 100 days in office, unleashing $400 billion to expand vaccinations and to reopen schools, $1,400 direct payments to households, and other priorities, including a gradual increase in the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour. Failure would be a high-profile setback early in his presidency.

The Biden team has largely focused on direct outreach to lawmakers, but that has failed to generate much public pressure that could make Republicans more willing to reach a deal on the administration’s timeline.

A Republican Senate aide said that lawmakers’ offices are not being bombarded with calls for an additional aid package, saying that constituents are mainly focused on the looming impeachment trial. The aide spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss private conversations.

Democrats in the House and the Senate are operating as though they know they are on borrowed time. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi are laying the groundwork to start the go-it-alone approach as soon as next week.

They are drafting a budget reconciliation bill that would start the process to pass the relief package with a simple 51-vote Senate majority — rather than the 60-vote threshold typically needed in the Senate to advance legislation. The goal would be passage by March, when jobless benefits, housing assistance and other aid is set to expire.

Schumer said he drew from Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s advice to “act big” to weather the COVID-19 economic crisis.

“Everywhere you look, alarm bells are ringing,” Schumer said from the Senate floor.

Senate Republicans in a bipartisan group warned their colleagues in a “frank” conversation late Wednesday that Biden and Democrats are making a mistake by loading up the aid bill with other priorities and jamming it through Congress without their support, according to a person familiar with the matter who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the private session.

Sen. Rob Portman, R-Ohio, a former White House budget director under George W. Bush, wants a deeper accounting of what funds remain from the $900 billion coronavirus aid package from December.

“Literally, the money has not gone out the door,” he said. “I’m not sure I understand why there’s a grave emergency right now.”

Biden spoke directly with Republican Sen. Susan Collins of Maine, who is leading the bipartisan effort with Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., that is racing to strike a compromise.

Collins said she and the Democratic president had a “good conversation.”

“We both expressed our shared belief that it is possible for the Senate to work in a bipartisan way to get things done for the people of this country,” she said.

The emerging debate is highly reminiscent of the partisan divide over the 2009 financial rescue in the early months of the Obama administration, when Biden was vice president, echoing those battles over the appropriate level of government intervention. The difference then is that then-President Barack Obama and Biden could tour the country to rally support, an option that is more difficult amid a pandemic.

On Thursday, more than 120 economists and policymakers signed a letter in support of Biden’s package, saying the $900 billion that Congress approved in December before he took office was “too little and too late to address the enormity of the deteriorating situation.”

Employers shed workers in December, retail sales have slumped and COVID-19 deaths kept rising. More than 430,000 people in the U.S. have died from the coronavirus.

At the same time, the number of Americans applying for unemployment benefits remained at a historically high 847,000 last week, and a new report said the U.S. economy shrank by an alarming 3.5% last year.

“The risks of going too small dramatically outweigh the risks of going too big,” said Gene Sperling, a former director of the White House National Economic Council, who signed the letter.

The government reported Thursday that the economy showed dangerous signs of stalling in the final three months of last year, ultimately shrinking in size by 3.5% for the whole of 2020 — the sharpest downturn since the demobilization that followed the end of World War II.

The decline was not as severe as initially feared, largely because the government has steered roughly $4 trillion in aid, an unprecedented emergency expenditure, to keep millions of Americans housed, fed, employed and able to pay down debt and build savings amid the crisis.

Republican allies touted the 4% annualized growth during the last quarter, with economic analyst Stephen Moore calling the gains “amazing.”

Republicans have also raised concerns about adding to the deficit, which skyrocketed in the Trump administration.

Republican Sen. John Barrasso of Wyoming, the third-ranking party leader, said Biden should stick to the call for unity he outlined in his inaugural address, particularly with the evenly split Senate. “If there’s ever been a mandate to move to the middle, it’s this,” he said. “It’s not let’s just go off the cliff.”