Teachers help students make sense of violence at US Capitol

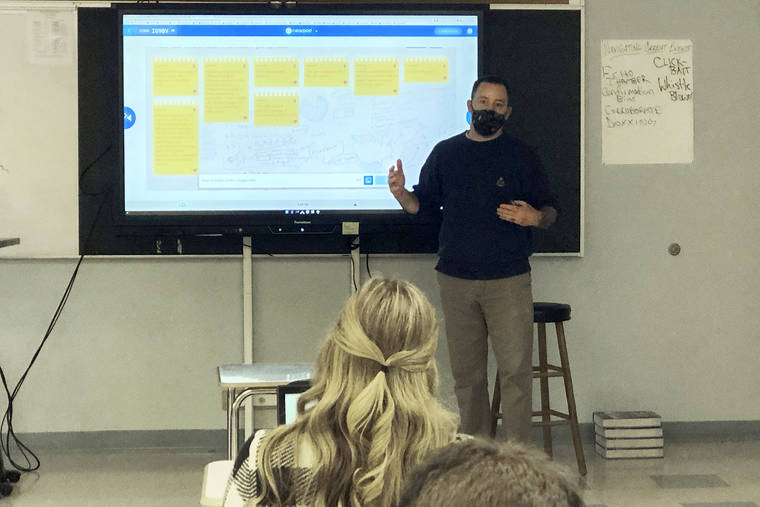

Conor Murphy, a teacher at West Genesee High School, in Camillus, N.Y., conducts his "Participation in Government" class, Thursday, Jan. 7, 2021. Many teachers say they are treading cautiously in light of varied political viewpoints in their classrooms and communities. But they universally describe efforts to hear out students’ fears and concerns. (Photo by A. Thomson via AP)

A teacher in Alabama presented photographs of the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol without commentary and asked students to write poems in reflection. A Minnesota instructor fielded comparisons to the aftermath of George Floyd’s killing. And a civics educator in Connecticut urged her rattled students to work toward making the country better.

A teacher in Alabama presented photographs of the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol without commentary and asked students to write poems in reflection. A Minnesota instructor fielded comparisons to the aftermath of George Floyd’s killing. And a civics educator in Connecticut urged her rattled students to work toward making the country better.

Social studies teachers nationwide set aside lesson plans this week to help young people make sense of the scenes of the violent siege in Washington by supporters of President Donald Trump.

Approaches varied, with some teachers deliberately holding off on historical comparisons with the events so fresh. Many trod cautiously in light of varied political viewpoints in their classrooms and communities.

But educators universally described efforts to hear out students’ fears and concerns and instill a sense of history and even hopefulness in a school year shaped by the nation’s reckoning over racial injustice, the coronavirus pandemic and the constraints of distance learning.

“In almost every single one of my classes, the students brought it up before I even could,” said Karley Reising, a social studies teacher at Robert E. Fitch High School in Groton, Connecticut. “And especially my seniors were really struggling with what this meant about the future of our country in a way that was pretty heartbreaking.”

She and others said they tried to focus on the importance of engagement and to push back against the creeping sense that violence is the inevitable end to political division.

“This was one of the most important days as a teacher, not even just a history teacher,” Michael Neagle said after wrapping up with his students at Lowell High School in Massachusetts the day after the siege. “We don’t want kids to tune out and just say, ‘Well, this is how it is. Nobody gets along. Politics.’ That voter apathy is so dangerous.”

After watching events unfold on television, the world history and civics teacher stayed up most of the night exchanging emails with his department chair, planning out lessons around what was unfolding.

“I don’t have many nights where I’m up til 3 o’clock in the morning with curriculum,” Neagle said, “but we have to take advantage of it.”

South St. Paul, Minnesota, teacher Mark Westpfahl set aside his planned lesson on state treaties and instead grabbed the morning newspapers with their “Insurrection” headlines to use as visual aides to teach his sixth grade students, who are learning remotely. Just miles from the fiery clashes ignited by Floyd’s death, there were questions from his students about the police response that will carry into lessons next week.

“That’s the connection that we’re going to bring in on Monday, is how do these two events correlate with each other? What was the response like? What was the media presence like?” he said.

As he taught his 10- and 11-year-old students over video, three or four parents made their way into view on his screen but didn’t interrupt.

In such a fraught political climate, Westpfahl said, “you are wondering, are you listening because you’re finding this fascinating and interesting, or are you listening because you want to question everything that I’m saying or doing?”

In deeply conservative Alabama, 10th grade teacher Blake Busbin said he, too, considered how his presentation and language could be perceived by students and the community and said he is “very purposeful with the language I use, choosing what words to utilize.”

Busbin, a teacher at Auburn High School, made a point to let students watch the chaos unfold on TV. He was a high school senior on 9/11 and the school principal ordered a media blackout, which he felt cost him an opportunity to watch history in the making.

The day after the Capitol siege, he rose before dawn and gathered 25 photographs that he showed for 10 to 15 seconds each without saying anything, then asked students to write poems. He wanted it to be day a of reflection.

“My strategy, as I told my students, I like to consider myself kind of like a grill master,” he said. “Before you put the meat on the grill, it needs to marinate for a while.”

The students submitted the poems anonymously, and they weren’t read in class. Busbin said they helped him understand students’ frame of mind and will help guide future instruction.

The poems, he said, show a desire for a more harmonious government, a more bipartisan approach and a belief that things can get better.

“It’s been a year of hurt. Certainly having student family members who have passed away, having students who were ill,” he said. “My fear is that there is that we’re almost become numb to the hurt that we felt throughout this year.”

The poems, Busbin said, show a desire for a more harmonious government, a bipartisan approach and a belief that things can get better.

In David McMullen’s classroom at Great Path Academy in Manchester, Connecticut, politics emerged when a student addressed unfounded claims that it was a false flag operation. Another student stepped in and said even if that were the case, the president and supporters had encouraged the mob nonetheless.

“Today was just to kind of soak in the events and talk about them and write some stuff down, because, as I tell my students, they are the future’s primary sources,” he said.

McMullen and other teachers also heard out students who were deeply affected by the photographs of Confederate flags carried through the halls of Capitol and who saw a double standard in the heavier response by police to Black Lives Matter protests.

Reising said the conversation among her students was strained by their hybrid learning model, and because some have not even met face to face. But she tried to end the discussion on a hopeful note.

“I just turn it into, ‘Hopefully for you and maybe for others in our country, this will be the thing that lights the fire on what it means to be an active, engaged citizen. And if you didn’t like what you saw, then what steps can you take to make sure this doesn’t happen again?’”

New York teacher Conor Murphy thought back to 9/11, when he was in an American history class and watched the second plane hit the World Trade Center.

“One of the challenges is to appropriately signify the gravity,” Murphy said, recalling a similar challenge a year ago while teaching participation in government at West Genesee High School in Camillus during Trump’s impeachment trial.

“But,” he said, “I’ve never really had to teach anything quite so, in my opinion, profound.”