Coral reefs are among the most highly biodiverse ecosystems on Earth, yet it is not clear what drives speciation and diversification in the ocean, where there are few physical barriers that could separate populations. Diversity in Hawaiian corals is likely driven by coevolution between the coral host, the algal symbiont (algae living in close and prolonged interaction) and the microbial community. That’s according to a study led by the University of Hawaii at Manoa’s Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB).

Coral reefs are among the most highly biodiverse ecosystems on Earth, yet it is not clear what drives speciation and diversification in the ocean, where there are few physical barriers that could separate populations. Diversity in Hawaiian corals is likely driven by coevolution between the coral host, the algal symbiont (algae living in close and prolonged interaction) and the microbial community. That’s according to a study led by the University of Hawaii at Manoa’s Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB).

As coral reef ecosystems have rapidly collapsed around the globe over the past few decades, there is widespread concern that corals might not be able to adapt to changing climate conditions, and much of the biodiversity in these ecosystems could be lost before it is studied and understood.

The team of researchers used massive amounts of metagenomic sequencing data to understand what may be some of the major drivers of adaptation and variation in corals.

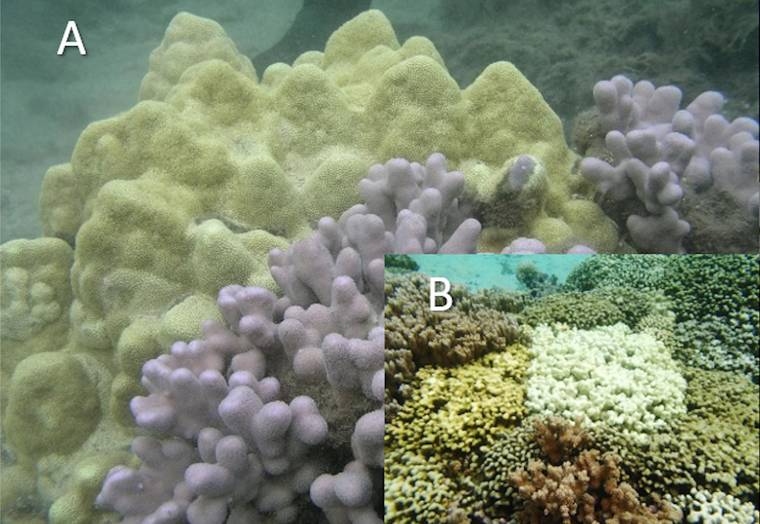

“Corals have incredible variation with such a wide range of shapes, sizes and colors that it’s really hard for even the best trained experts to be able to sort out different species,” said Zac Forsman, an HIMB assistant researcher and lead author of the study. “On top of that, some corals lose their algal symbionts, turning stark white or ‘bleached’ and die during marine heatwaves, while a similar looking coral right next to it seems fine. We wanted to try to better understand what might be driving some of this incredible variation that you see on a typical coral reef.”

Forsman and colleagues examined genetic relationships within the coral genus Porites, which forms the foundation and builds many coral reefs around the world. They were able to identify genes from the coral, algal symbionts and bacteria that were most strongly associated with coral bleaching and other factors such as the shape (morphology) of the coral colony. They found relatively few genes associated with bleaching, but many associated with distance from shore, and colony morphologies that dominate different habitats.

“We sought out to better understand coral bleaching and place it in the context of other sources of variation in a coral species complex,” said Forsman. “Unexpectedly, we found evidence that these corals have adapted and diverged very recently over depth and distance from shore. The algal symbionts and microbes were also in the process of diverging, implying that coevolution is involved. It’s like we caught them in the act of adaptation and speciation.

“These corals have more complex patterns of variation related to habitat than we could have imagined and learning about how corals have diversified over various habitats can teach us about how they might adapt in the future,” he explained. “Since variation is the raw material for adaptation, there is hope for the capacity of these corals to adapt to future conditions, but only if we can slow down the pace of loss.”