Parents: Online learning program has racist, sexist content

HONOLULU — Zan Timtim doesn’t think it’s safe for her eighth-grade daughter to return to school in person during the coronavirus pandemic but also doesn’t want her exposed to a remote learning program that misspelled and mispronounced the name of Queen Lili‘uokalani, the last monarch to rule the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Timtim’s daughter is Native Hawaiian and speaks Hawaiian fluently, “so to see that inaccuracy with the Hawaiian history side was really upsetting,” she said.

Even before the school year started, Timtim said she heard from other parents about racist, sexist and other concerning content on Acellus, an online program some students use to learn from home.

Parents have called out “towelban” as a multiple-choice answer for a question about a terrorist group and Grumpy from “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” described as a “woman hater.” Some also say the program isn’t as rigorous as it should be.

As parents help their children navigate remote classes, they’re more aware of what’s being taught, and it’s often not simply coming from an educator on Zoom. Some schools have turned to programs like Acellus to supplement online classes by teachers, while others use it for students who choose to learn from home as campuses reopen. And because of the scramble to keep classes running during a health crisis, vetting the curriculum may not have been as thorough as it should have been, experts say.

Thousands of schools nationwide use Acellus, according to the company, and parents’ complaints are leading some districts to reconsider or stop using the program.

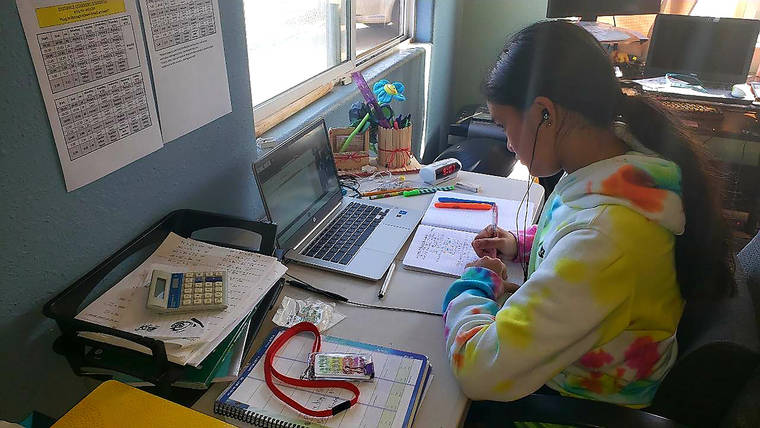

“We wouldn’t have had this visibility if it weren’t for all of us at home, often sitting side by side and making sure: ‘Is this working for you?’” said Adrienne Robillard, who withdrew her seventh-grade daughter from Kailua Intermediate School after concluding Acellus lacked substance and featured racist content.

When school officials said her daughter could do distance learning without Acellus, Robillard reenrolled her.

Acellus officials didn’t respond to multiple calls from The Associated Press seeking comment. In an online message to parents, founder Roger Billings called the controversy “an organized attack” and said “they have not found anything in our content that is really racist or sexist.” An automated closed-captioning system misinterpreted some words, he said.

Kansas City, Missouri-based Acellus was created in 2001, according to its website, which says it “delivers online instruction, compliant with the latest standards, through high-definition video lessons made more engaging with multimedia and animation.”

In a video on his website, Billings responds to criticism about his credentials by saying he earned a bachelor’s degree in “composite fields” of chemistry, physics, engineering and other subjects from a university he doesn’t name. He says he started a company focused on hydrogen energy technology and that he later earned a “doctor of research and innovation” degree at the International Academy of Science, the nonprofit that develops Acellus courses.

Hawaii selected Acellus based on an “implementation timeline” as well as “cost effectiveness” and other factors, Superintendent Christina Kishimoto said in a memo.

“I don’t think it’s unreasonable to think that price was the main factor,” said Charles Lang, visiting assistant professor of learning analytics at Columbia University’s Teachers College in New York City. “And to some extent, you do get what you pay for in terms of content.”

Vetting educational programs takes time, but with the pandemic, districts needed to quickly find remote learning platforms, said Eric Hirsch, executive director of EdReports, which helps schools review instructional materials.

“So this spring, we saw a scramble, a dash,” he said.

And evaluating curriculum is like the “Wild West” — it varies across school systems, Lang said.

“We were in some serious situations with the pandemic, and we had to figure something out,” Hawaii school board member Kili Namau‘u said at a recent meeting. “And I think schools made some pretty quick decisions. Maybe they weren’t the most accurate decisions.”

She later said in an interview that it would be more problematic to pull Acellus in the middle of the quarter.

But as a Native Hawaiian, she wants to ensure Acellus has corrected “appalling” and inaccurate information about Hawaiian history: “I’m particularly dismayed with that particular module.”

Seeing the queen’s name misspelled and information that the Hawaiian islands were “discovered” by Europeans was enough for Timtim and her husband to decide their daughter should join Waipahu Intermediate School’s hybrid remote and in-person program despite their concerns about COVID-19.

Then most of Hawaii’s public schools, which began virtually on Aug. 17, extended remote learning until mid-October.

“I just pray we figure out what to do if she does have to go to school once or twice a week,” Timtim said.

The Hawaii Department of Education, the nation’s only statewide school district, is considering what to do about Acellus, but some schools decided on their own to stop using it. Other U.S. districts, like Alameda Unified in California, quickly dropped the program after complaints surfaced.

In a recent memo, the California Department of Education said it “has learned through examples shared that Acellus lessons may contain highly inappropriate content and may not meet state legal requirements surrounding instructional materials.” The memo to superintendents and school administrators cited “racist depictions of Black Americans” and “at least one question that perpetuates Islamophobic stereotypes.”

A Sept. 17 memo Hawaii’s superintendent sent to the school board said education officials were working with Acellus to address inappropriate content.

Mariko Honda-Oliver heard concerning things from other parents but didn’t find anything she considered racist. She was troubled, however, that her son, a second-grader at Makalapa Elementary, blew through more than a week of material on his first day.

Similarly, Cassie Favreau-Chung said her son, a freshman at Mililani High School, was looking forward to the independence of remote learning but found he wasn’t getting a quality education because the program had no writing assignments.

“He hasn’t found anything on his own that he thought was racist or sexist,” she said. “However, I will also say that a lot of kids, it’ll go over their heads.”

For example, “towelban,” Favreau-Chung said.

She switched her son to the hybrid program next quarter to avoid Acellus, hoping the school will let him keep learning from home.

The experience has made Favreau-Chung lose faith: “It’s the first time that I have not been proud to have my kid in public school.”

Honda-Oliver, whose military family has experienced schools worldwide, also is disappointed.

“This experience of having to see how other districts and other states are doing distance learning compared to Hawaii has kind of reinforced that Hawaii really is not the place to come if you want to give your children a good education,” she said.