HONOLULU — The Hawaii Supreme Court heard arguments Friday on the legality of issuing licenses to foreign workers in Hawaii’s longline commercial fishing fleet, which for years has been under scrutiny after an Associated Press investigation revealed claims of human trafficking and questionable labor practices.

The case involves the issuance of Hawaii state commercial fishing licenses to individual foreign fishermen who are not “lawfully admitted” to the United States.

State law says only those legally in the country can get state licenses to catch and sell marine life but the workers do not have visas to enter the U.S. and are ordered to live onboard vessels by federal officials. They must eat, sleep and work on the boats, often for years at a time, and are subject to deportation.

Friday’s hearing stems from a petition that was filed by a Native Hawaiian fisherman who sought to have the state enforce a statute that declares only people who are in the U.S. legally can acquire commercial fishing licenses.

The petition was denied by the Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources, which issues the permits, and a lower court upheld the ruling before the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case.

The attorney for the state argued Friday that the workers are in fact lawfully admitted even though they are officially detained on board.

“The issue of whether or not the crew members are lawfully admitted under the terms of the statute is addressed in the conclusions of law,” said Deputy Attorney General William Wynhoff in representing Hawaii.

The federal government “knows these people are here. They’re in the United States, in the waters of the United States, and they’re lawfully admitted. They can’t come on shore, but they’re on a boat in the United States,” Wynhoff said. “Nobody’s making them go away.”

The fishermen are allowed to fish in Hawaii under a loophole in federal law that allows those seeking highly migratory species such as tuna to utilize foreign labor to take those fish. Other fishing fleets in the United States are required to have mostly American crews.

An attorney for the Hawaii Longline Association argued that the workers were not taking fish in waters exclusively controlled by state authorities because federal law applies to the majority of the fishing grounds in the Pacific.

“The court found explicitly that the boats do not fish closer than 50 miles to the north and east or 100 miles to the south and west of the main Hawaiian islands,” said Geoffrey Davis on behalf of the Hawaii longline fishing industry. “So part of this rests on how far out the state has jurisdiction over fishing in those waters.”

The state shares jurisdiction and enforcement of the fishery with federal authorities in waters up to 200 miles off shore.

Interpretations of law were disputed by Lance Collins, attorney for the plaintiff Malama Chun, who asserts as a Native Hawaiian he has cultural and traditional rights to challenge the state because its rules impede his ability to access a resource, mostly tuna, within the area of ocean controlled by the state.

“There’s two issues that Mr. Chun is very concerned about. One is the continuing decline of his ability to engage in his traditional and customary practice of fishing which of course ties in to the state’s obligation under the public trust doctrine to protect marine resources,” Collins said.

But he said Chun is equally concerned about the way the foreign crews are treated.

“Mr. Chun’s position is that the labor practices and the situation where individuals who work on these ships are not able to meaningfully connect with legal process or otherwise vindicate their rights with respect to labor and health and safety in the state of Hawaii does impact the obligation of the state to protect the vulnerable and the weak,” Collins said.

He said his client has the right to live in a society where “things that look like modern day slavery or human trafficking are not permitted to occur or the state will not facilitate that any way.”

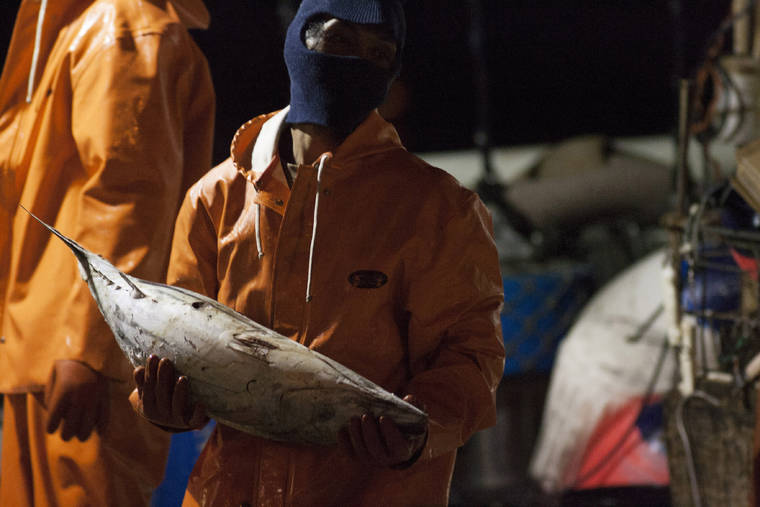

The foreign crews, about 700 men mostly from Pacific island nations and Southeast Asia, are allowed to get off their vessels while docked at gated piers and move around the immediate area, but they cannot leave the dock and must live aboard the boats, often in cramped, unsanitary conditions. They are not protected by U.S. or state labor laws.

Previous efforts by local and federal lawmakers to address concerns in the fishery have fallen flat, and subsequent efforts by Hawaii residents have been similarly unsuccessful.

The fishermen are paid as little as $350 a month, but still more than they can make in their home countries where people live on less than a dollar a day. Many workers also get small bonuses, boosting their monthly pay to $500 or $600. A few get a percentage of the catch, making it possible to triple their wages.

The Honolulu fleet is among the most profitable in the nation and a single fish can sometimes sell for $1,000 or more.

The men work long hours — 12 to 20 hours a day — setting thousands of hooks on miles of fishing line that is drifted behind the boats. Like any job in fishing, one of the most dangerous occupations, injuries and deaths are common.

Last week, a 53-year-old Vietnamese man working on a Honolulu-based longline boat was reported missing in the early morning hours. The Coast Guard said the man was not wearing a flotation device when he was last seen around 4 a.m. on the vessel St. Marie Anne. Officials suspended their search for the fisherman after scouring an area roughly the size of New Hampshire.

The court will take some time to consider the arguments before making a ruling.