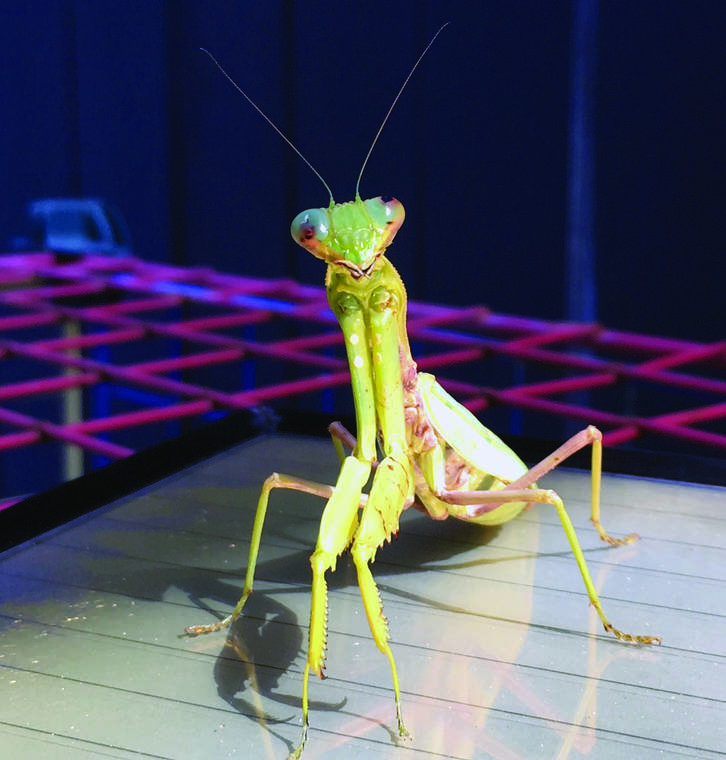

From a distance, the dead leaf praying mantis resembles its namesake: brown, crispy and still. Inch a little closer and it looks the same. But go even closer — too close — and a transformation occurs. The mantis whirls around, spreads its black-patterned wings and puts its arms behind its head in a pose reminiscent of Edvard Munch’s “The Scream,” showing off shocking red undersides.

This performance is called a startle display. Creatures across the animal kingdom use different varieties of this fancy defense to foil would-be predators: Octopuses change colors, lizards puff up their frills and moths unfold to reveal spooky eyespots.

But despite their flair, startle displays are “poorly understood,” said Kate Umbers, an evolutionary biologist at Western Sydney University. It’s not clear how they evolved or what makes them effective.

For a paper published this week in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Umbers and her colleagues investigated these mysteries by comparing the displays of several dozen praying mantis species.

Fascinated observers have been describing the praying mantis’ startle displays since at least 1841, when a French entomologist started tickling his pet European mantis with a feather and taking notes.

The accounts covered 58 species, just over half of which had been seen performing startle displays. Many had unique combinations of moves. The Congo green mantis opens its mouth, shows its colorful forelegs and spreads its wings. The devil’s flower mantis moves its forelegs back and forth and clicks, like a haunted clock.

Umbers and her colleagues rated the complexity of each species’ display. They then mapped these scores onto a mantis evolutionary tree, incorporating information about each type’s size and shape.

They found that, contrary to what they expected, larger species did not necessarily have more complex startle displays. Neither did those that couldn’t fly. Instead, groups of closely related species “were more likely to have startle displays, and more likely to have complex startle displays” than those with fewer close relatives, Umbers said.

Closely related species tend to share habitats and predators. If all the nearby mantises struck the same weird pose, the local mantis-eaters might become familiar with it and stop being thrown off. Intriguingly, these displays began evolving about 60 million years ago — soon after the extinction of the dinosaurs spurred modern birds, a key mantis predator, to diversify, Umbers said.

© 2020 The New York Times Company