JEFFERSON CITY, Mo. — Many state and local governments across the country have suspended public records requirements amid the coronavirus pandemic, denying or delaying access to information that could shed light on key government decisions.

Public officials have said employees either don’t have the time or ability to compile the requested documents or data because they are too busy responding to the outbreak or are working from home instead of at government offices.

The result is that government secrecy has increased at the same time officials are spending billions of dollars fighting the COVID-19 disease and making major decisions affecting the health and economic livelihood of millions of Americans.

That’s raised concerns among open-government advocates.

“It’s just essential that the press and the public be able to dig in and see records that relate to how the government has responded to the crisis,” said David Snyder, executive director of the First Amendment Coalition, a California-based nonprofit. “That’s the only way really to avoid waste, fraud, abuse and to ensure that governments aren’t overstepping their bounds.”

The nonprofit Reporters Committee for the Freedom of the Press has tracked more than 100 instances in at least 30 states and the District of Columbia in which state agencies, counties, cities or other public entities have suspended requirements to respond to open-records requests by regular deadlines or told people to expect delays.

Some governors have issued decrees allowing record requests to be put on hold for as long as the coronavirus emergency continues. Others have extended response deadlines by days, weeks or even months.

Various federal agencies also have said there may be delays in processing public records requests. The FBI temporarily stopped accepting electronic records requests in March, citing the coranvirus, but has since resumed. It’s website now says record-seekers “can expect delays.”

A bipartisan group of U.S. senators has raised concerns and asked the federal Office of Information Policy to outline any steps it’s taking to protect the public’s right to information.

Hawaii Gov. David Ige, a Democrat, issued one of the most sweeping orders, suspending the state’s entire open-records law in mid-March. Following an outcry among open-records advocates, Ige revised his order last week. The new order still suspends specific deadlines to provide records but encourages agencies to acknowledge and respond to requests “as resources permit.”

Attorney Brian Black, who helped negotiate the compromise, described Ige’s original order as “extreme and unnecessary.”

“The public records law exists to give people the ability to hold their government accountable, and without timely access to information, they can’t do it,” said Black, executive director of The Civil Beat Law Center for the Public Interest in Honolulu.

Honolulu Civil Beat, an online publication financed by the same source as the center, has had a records request related to a public transit board pending since March. It also had sought a document related to a dispute about whether the state’s airports should be closed to tourists because of the coronavirus.

Public records are “a way of validating, corroborating what these elected officials are telling us,” said the publication’s editor, Patti Epler.

The Associated Press also has records requests pending in various states where responses have been delayed because of the coronavirus.

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton and the Pennsylvania Office of Open Records have issued similar advice effectively relaxing open-records requirements. They said days when public offices are physically closed because of the coronavirus don’t count toward the normal deadlines to respond to record requests.

The Pennsylvania office also posted a notice on its website, stating: “Requesters: Unless you have an urgent need to access records, please do not file any new Right-to-Know Law (RTKL) requests at this time.”

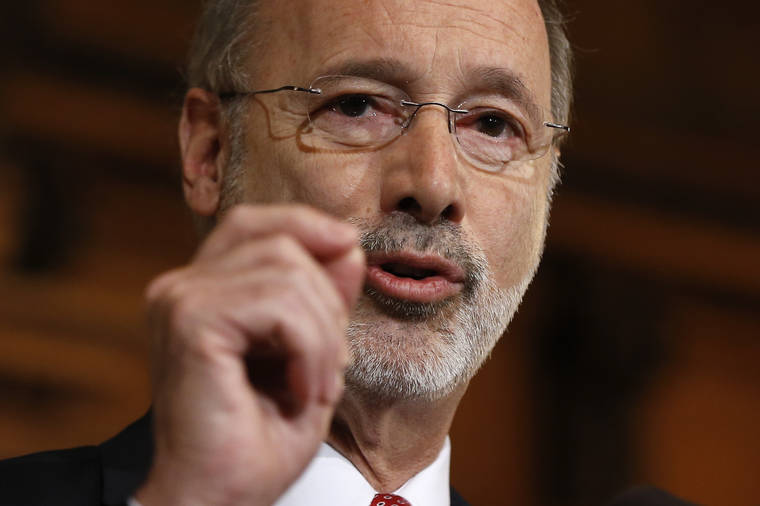

The Republican-led Legislature has mounted a backlash targeted at Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf’s administration. The House overwhelmingly passed legislation last week that would require Pennsylvania agencies to respond to records requests during disaster declarations, even when their physical offices are closed. The bill is pending in the Senate.

“Government transparency cannot stop during times of crisis,” said the bill’s sponsor, Republican Rep. Seth Grove.

New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy, a Democrat, signed a law in March suspending the state’s seven-business-day deadline to respond to record requests during emergencies, as long as agencies “make a reasonable effort, as the circumstances permit.”

Republican Sen. Declan O’Scanlon, one of the sponsors of the new law, said he pushed for it out of concern that county and town officials could be overwhelmed while simultaneously dealing with the virus and trying to respond to requests.

“We have to understand they’re human beings behind these requests, and providing some leeway is reasonable,” he said.

Governors from Washington to Michigan to Rhode Island also have used their executive powers to waive or extend response deadlines for open-records requests.

Delaware Gov. John Carney changed the regular response deadline of 15 business days to instead allow up 15 business days after the end of his emergency declaration.

The city of Portland, Oregon, also has suspended responses to open-records requests as long as a declaration of emergency is in effect.

“Things like that are especially problematic, because we have no idea when these states of emergencies are going to end,” said Gunita Singh, an attorney at the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, based in Washington, D.C. “Who knows how long these individual requesters are going to be waiting to have their public records requests fulfilled?”

Even in states where governors have not suspended public records laws, information has sometimes been hard to come by during the coronavirus outbreak.

California’s Constitution includes a “right of access to information,” specifically stating that “the writings of public officials and agencies shall be open to public scrutiny.”

Yet Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom declined for a while to release details of a nearly $1 billion contract to buy protective masks from a Chinese company. And numerous California municipalities have stopped or slowed their fulfillment of open-records requests.

The city of Burbank said in an online notice that responses to public records requests by legal deadlines “are not essential services.”

San Diego County said it was delaying responses to records requests related to the COVID-19 disease but continuing to fulfill ones on other topics.

County spokesman Michael Workman declined to explain the reason for the distinction while noting that staff are focused on essential services for the foreseeable future.

“There are some county employees teleworking, so if they can provide requested documents, they do,” Workman said.

Associated Press writer Michael Catalini in Trenton, New Jersey, contributed to this report.