Trump acquittal on track, though Romney to vote to convict

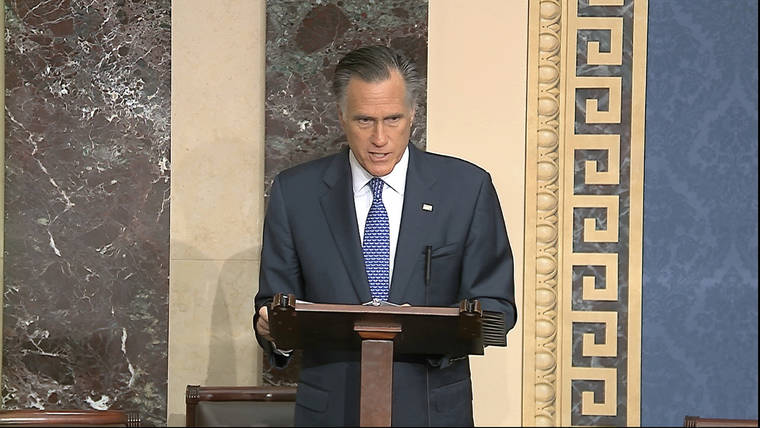

In this image from video, Sen. Mitt Romney, R-Utah, speaks on the Senate floor about the impeachment trial against President Donald Trump at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, Wednesday, Feb. 5, 2020. The Senate will vote on the Articles of Impeachment on Wednesday afternoon. (Senate Television via AP)

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., leaves a meeting with fellow Democrats at the Capitol in Washington, Wednesday, Feb. 5, 2020. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

FILE - In this Jan. 31, 2020 file photo, Sen. Doug Jones, D-Ala., is questioned by reporters as he arrives at the Capitol for the impeachment trial of President Donald Trump on charges of abuse of power and obstruction of Congress, in Washington. Jones, the most endangered Democrat in this November's elections, said Wednesday that he will vote to convict President Donald Trump Wednesday as the Senate impeachment trial reaches its climax. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Lead House impeachment manager, Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff, D-Calif., arrives to meet with fellow Democrats at the Capitol in Washington, Wednesday, Feb. 5, 2020. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, heads to a waiting elevator on Capitol Hill, Tuesday, Feb. 4, 2020, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

Sen. John Kennedy, R-La., speaks with reporters on Capitol Hill, Tuesday, Feb. 4, 2020 in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

WASHINGTON President Donald Trump is on the verge of acquittal by the Senate, bringing an end to only the third presidential impeachment trial in American history in a vote at the start of the tumultuous campaign for the White House.

WASHINGTON — President Donald Trump is on the verge of acquittal by the Senate, bringing an end to only the third presidential impeachment trial in American history in a vote at the start of the tumultuous campaign for the White House.

A majority of senators have now expressed unease with Trump’s pressure campaign on Ukraine that resulted in the two articles of impeachment. But there’s nowhere near the two-thirds support necessary in the Republican-held Senate for the Constitution’s bar of high crimes and misdemeanors to convict and remove the president from office.

One key Republican, Sen. Mitt Romney of Utah, announced on the Senate floor that he was breaking with his party. Romney appeared to choke up as he spoke of his deep faith and “oath before God” demanding that he vote for impeachment.

“The president is guilty of an appalling abuse of public trust,” Romney said on the Senate floor. “What the president did was wrong, grievously wrong.”

The final outcome expected Wednesday caps nearly five months of remarkable impeachment proceedings launched in Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s House, ending in Mitch McConnell’s Senate and reflective of the nation’s unrelenting partisan divide three years into the Trump presidency.

No president has ever been removed by the Senate, and Trump arrived at the Capitol for his State of the Union address on the eve of the vote eager to use the tally as vindication, a political anthem in his reelection bid. Allies chanted “four more years!”

The president did not mention impeachment. The mood was tense in the House that impeached him. Pelosi tore up the speech when he was done.

The Wednesday afternoon vote is expected to be swift. With Chief Justice John Roberts presiding, senators sworn to do “impartial justice” will stand at their desk for the roll call and state their votes — “guilty” or “not guilty.”

On the first article of impeachment, Trump is charged with abuse of power. On the second, obstruction of Congress.

Few senators are expected to stray from party camps, all but ensuring the highly partisan impeachment yields deeply partisan acquittal. Both Bill Clinton in the 1999 and Andrew Johnson in 1868 drew cross-party support when they were left in office after an impeachment trial. President Richard Nixon resigned rather than face revolt from his own party.

Ahead of voting, some of the most closely watched senators took to the Senate floor to tell their constituents, and the nation, what they had decided. The Senate chaplain has been opening the trial proceedings with daily prayers for the senators.

“This decision is not about whether you like or dislike this president,” began GOP Sen. Susan Collins, the Maine centrist, announcing her resolve to acquit on both charges.

GOP Sen. Rob Portman of Ohio said that while he doesn’t condone Trump’s actions, he was not prepared to remove him from the ballot nine months before the election. “Let the people decide,” he said.

Centrist Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia has floated the idea of censuring Trump instead, a signal of a possible vote to acquit.

One key Democrat, Alabama Sen. Doug Jones — perhaps the most endangered politically for reelection in a state where Trump is popular — announced ahead of the vote that after many sleepless nights he had decided to vote to convict on both charges.

“Senators are elected to make tough choices,” Jones said in a statement. He noted the “gravity of this moment,”’ and said Trump’s actions were “more than simply inappropriate. They were an abuse of power. With impeachment as the only check on such presidential wrongdoing, I felt I must vote to convict.”

Most Democrats, though, echoed the House managers’ warnings that Trump, if left unchecked, would continue to abuse the power of his office for personal political gain and try to “cheat” again ahead of the the 2020 election.

During the nearly three-week trial, House Democrats prosecuting the case argued that Trump abused power like no other president in history when he pressured Ukraine to investigate Democratic rival Joe Biden ahead of the 2020 election.

They detailed an extraordinary shadow diplomacy run by Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani that set off alarms at the highest levels of government. Trump, after asking Ukraine’s president for “a favor” in a July 25 phone call, temporarily halted U.S. aid to the struggling ally battling hostile Russia at its border.

When the House probed Trump’s actions, he instructed White House aides to defy congressional subpoenas, leading to the obstruction charge.

Questions from the Ukraine matter continue to swirl. House Democrats may yet summon former national security adviser John Bolton to testify about revelations from his forthcoming book that offer a fresh account of Trump’s actions. Other eyewitnesses and documents are almost sure to surface.

House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jerrold Nadler said Wednesday that Democrats are “likely” to subpoena Bolton but that a final decision hadn’t yet been made.

In closing arguments for the trial the lead prosecutor, Rep. Adam Schiff, D-Calif., appealed to senators’ sense of decency, that “right matters” and “truth matters”’ and that Trump “is not who you are.”

“You can’t trust this president to do the right thing, not for one minute, not for one election, not for the sake our country,” Schiff intoned. “He will not change. And you know it.”

Pelosi was initially reluctant to launch impeachment proceedings against Trump when she took control of the House after the 2018 election, dismissively telling more liberal voices that “he’s not worth it.”

Trump and his GOP allies in Congress argue that Democrats have been trying to undercut him from the start. Trump calls both special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation of Russian interference in the 2016 election and the impeachment probe a “hoax” and says he did nothing wrong.

But a whistleblower complaint of his conversation with Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskiy set off alarms. When Trump told Pelosi in September that the call was perfect, she was stunned. “Perfectly wrong,” she said. Days later, the speaker announced the formal impeachment inquiry.

The result is a 28,000-page record from the House, based on testimony from 17 witnesses, including national security officials and ambassadors, in public and private depositions and House hearings.

The result was the quickest, most partisan impeachment in U.S. history, with no Republicans joining the House Democrats to vote for the charges. The Republican Senate kept up the pace with the fastest trial ever, and the first with no witnesses or deliberations.

Trump’s celebrity legal team with attorney Alan Dershowitz made the sweeping, if stunning, assertion that even if the president engaged in the quid pro quo as described, it is not impeachable, because politicians often view their own political interest with the national interest.

McConnell commands a 53-47 Republican majority and braced against dissent. Some GOP senators distanced themselves from Trump’s defense, and other Republicans brushed back calls from conservatives to disclose the name of the anonymous whistleblower. The Associated Press typically does not reveal the identity of whistleblowers.

Trump’s approval rating, which has generally languished in the mid- to low-40s, hit a new high of 49% in the latest Gallup polling, which was conducted as the Senate trial was drawing to a close. The poll found that 51% of the public views the Republican Party favorably, the first time the GOP’s number has exceeded 50% since 2005.

Associated Press writers Eric Tucker, Laurie Kellman, Matthew Daly, Alan Fram, Andrew Taylor and Padmananda Rama contributed to this report.