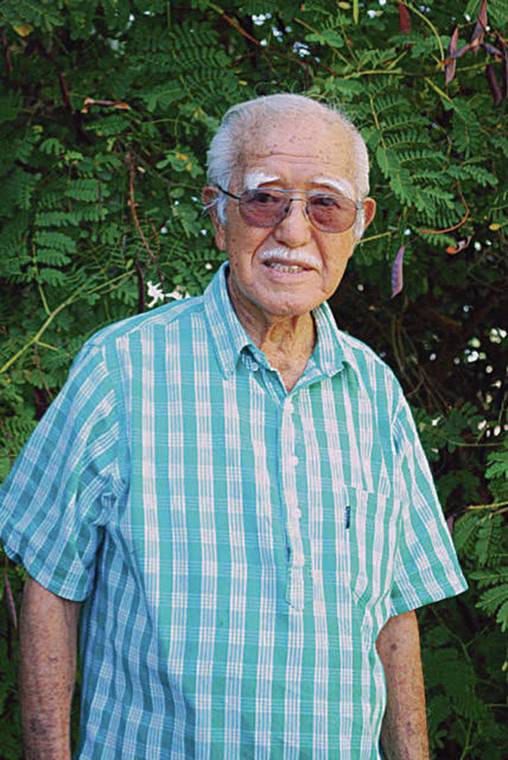

HONOLULU — Any story written about 20th-century Waipahu would almost certainly require that Goro Arakawa be featured prominently.

As a civic leader, historian, promoter and advocate, Arakawa devoted much of his life to ensuring Waipahu will always be remembered as the gritty and humble yet proud plantation town where immigrants from different homelands worked side by side in the cane fields and factories and developed a shared appreciation of each other.

A memorial service will take place today for Arakawa, who died Nov. 15. He was 97.

Arakawa was perhaps best known as the face of Arakawa’s, the iconic department store started by parents Zempan and Tsuru Arakawa. As the store’s longtime vice president in charge of advertising, credit and promotions, it was youngest son Goro Arakawa who ingrained in the minds of Oahu residents the inextricable link between Arakawa’s and the Waipahu Sugar Mill only several hundred feet away.

Less known, Goro Arakawa was instrumental in the development of the Waipahu Cultural Gardens and its Hawaii’s Plantation Villages, as well as the locating of the Leeward YMCA and Filipino Community Center on property that once made up Oahu Sugar’s mill, factory and administrative offices.

Yoshiko Yamauchi, a board member for the Waipahu Cultural Garden Park, said Arakawa’s drive and influence were critical to people’s understanding of what the plantations meant to Hawaii and its people.

“I don’t think plantation lifestyle would be (depicted) the way it is today,” Yamauchi said. “I think it would’ve been lost.”

Arakawa told her that it was during his time attending college on the East Coast that he gained an appreciation of the museums that depicted phases of American history and that it was the outdoor, living museums that he admired the most, Yamauchi said. As a result, the HPV puts much its focus on guided tours and interactive presentations featuring music lessons or ethnic dressing for school students.

Arakawa’s appreciation of the plantation lifestyle was evident from earlier in his life. While Arakawa’s was known in its later years for its unique array of merchandise, Arakawa understood the store’s history was rooted in the needs of the plantation workers it served, Yamauchi said. It sold tabis, gloves, raincoats and, of course, the gingham-patterned palaka shirts that were used because they were durable. Arakawa made palaka shirts a fashion statement, describing their significance in plantation life in small blurbs that ran in the Honolulu newspapers, she said.

It wasn’t just Arakawa’s in the ads.

“He slowly taught you about the plantation lifestyle,” Yamauchi said.

It didn’t stop there: Radio spots for Arakawa’s famously began with the crowing of a plantation rooster, and newspaper ads always featured a picture of the plantation and its sugar mill smokestack.

As for the cultural park and plantation village, “he had the foresight and was able to corral the people to get it done,” Yamauchi said.

Eldest son David Arakawa recalls his father holding ethnic festival days featuring food, entertainment and crafts, in the Arakawa’s parking lot.

Honolulu businessman Tim Johns was Amfac’s vice president of real estate development in the mid-1990s when he found himself and his company at odds with the mild-mannered Arakawa on the future of the mill site. Amfac’s initial plan was to redevelop all of its lands mauka of Waipahu Street, Johns said.

Arakawa had other plans.

“Slowly, patiently — but relentlessly — Goro explained to me how important it was for us to do what we could to help preserve those parts of Hawaii’s past that explain so much about how we are today,” Johns said. “He taught me how our sugar plantation past was so critical in making Hawaii the melting pot it became.”

Today the mill’s smokestack and generator are preserved and incorporated into the Leeward Y, while the FilCom Center was built nearby.

“He could see — when many could not — that the pace of change in Hawaii was accelerating so quickly that we were in real danger of losing the qualities that make Hawaii so special,” Johns said.

Despite his stubborn streak, those who knew Arakawa called him a good-humored and gentle man who loved playing ukulele and singing Hawaiian songs at parties. He lived humbly most of his life out of a family-owned walk-up apartment building in a modest section of Waipahu.

David Arakawa said his father was an eternal optimist who taught his children to “dream big, be creative and resourceful, always listen to advice from others and enlist the help of everyone.”

Goro Arakawa also told his children to “no get big head,” stay humble and to credit others for their work, his son said.

Sunday’s service at Mili lani Memorial Park Mauka Chapel begins at 10:30 a.m. Visitation starts at 9. A reception will follow. Palaka or casual attire is requested. No flowers.

Arakawa is survived by sons David, John and Woodrow; daughter Lei-Nani Arakawa-Brooke; 14 grandchildren; and 13 great-grandchildren. He was preceded in death by wife Mary and son Lance.