Schools, coaches more willing to fight NCAA allegations

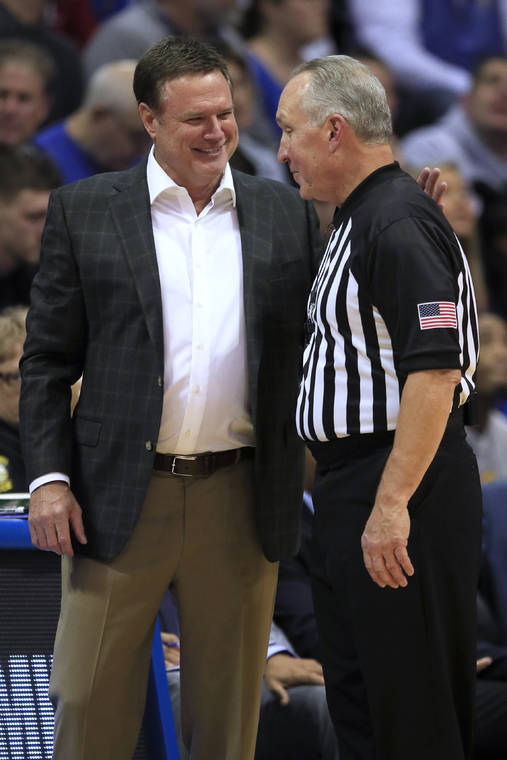

LAWRENCE, Kan. The ink on the NCAAs notice of allegations was but a few hours old when officials at Kansas huddled with Jayhawks coach Bill Self and crafted a strongly worded response that not only disputed the claims but went on the offensive.

LAWRENCE, Kan. — The ink on the NCAA’s notice of allegations was but a few hours old when officials at Kansas huddled with Jayhawks coach Bill Self and crafted a strongly worded response that not only disputed the claims but went on the offensive.

The tradition-rich program, which found itself in the crosshairs amid the FBI’s investigation of corruption in college basketball, instead suggested it was the victim in a play-for-pay scheme crafted by Adidas executives.

“We strongly disagree with the allegations,” athletic director Jeff Long said. “We fully support Coach Self and his staff and we will vigorously defend the allegations against him.”

So much for a cut-and-dried infractions case. Then again, few are these days.

The landscape of college sports has changed dramatically over the past 50 years, and the pace has only increased the past two decades. Massive television contracts worth billions of dollars, endorsement deals, coaching salaries and the amount of money pledged by well-heeled donors have raised the stakes to levels unimaginable when John Wooden was winning titles at UCLA.

The price of success is now measured in tens of millions of dollars. High-profile jobs are on the line every day. The reputation of an entire school is often tied to a single athletic program.

That’s why another change has occurred over the years: When schools run afoul the NCAA, they no longer blindly accept whatever punishment is meted out. Even those that suggest or levy self-punishments often close ranks and hunker down, hire outside counsel and vow to fight the penalties, big and small.

“There is some truth to that,” said David Ridpath, an associate professor of sports management at Ohio University and president of The Drake Group, a college athletics watchdog.

“The big schools can fight back harder,” Ridpath said, “and pay former NCAA investigators-turned-defensive point people a lot more money. So that is certainly an advantage.”

The moment Missouri was hit with wide-ranging allegations of academic fraud, much of it centered on its football program, the school turned to Mike Glazier of Kansas City-based law firm Bond, Shoeneck &King. Glazier has represented well over 100 schools and coaches in NCAA cases, including then-Indiana coach Kelvin Sampson and Louisville’s basketball program.

Glazier’s firm also represented North Carolina during its recent academic fraud case, and has been retained to help North Carolina State deal with its own basketball scandal. The Wolfpack were the first school to receive an NCAA notice as part of the FBI probe fallout.

Why is Glazier such an attractive attorney for schools? Among other reasons, he spent seven years working on the NCAA’s enforcement staff, giving him an inside look at the machinations of major college sports.

“More financial resources will enable any school or involved individual to hire the best attorneys and conduct a comprehensive investigation,” said Michael Buckner, whose Florida-based firm specializes in sports law. “In a few cases I handled, where I had access to excellent financial resources, I was able to interview more witnesses or collect more information than the enforcement staff.

“That allowed me to present a more detailed defense against the enforcement staff at the hearing,” Buckner continued. “Kansas is more than likely to follow the same strategy.”

Not just the school but its basketball coach, too.

Specifically targeted by the NCAA’s notice of allegations, Self has turned to Scott Thompsett of Tompsett Collegiate Sports Law — the “go-to counsel for coaches involved in NCAA investigations,” according to The National Law Journal — to help craft his defense. Tompsett is also helping former North Carolina State coach Mark Gottfried.

“We’re going to fight it,” Self said of the alleged NCAA violations, shortly before his third-ranked team opened a season of big expectations with an exhibition win last week. “We are aligned with the university, the athletic department and certainly our basketball program.”

It is difficult to gauge just how much a high-level defense will cost Kansas, given the myriad variables involved in each case. But in the case of Missouri’s academic scandal, an open-records request revealed the school had paid Glazier’s firm in excess of $350,000 over the past few years.

That may look like a small fortune, but it’s a fraction of the Tigers’ booming athletic budget. Just 15 years ago, the school reported athletic revenue of about $47 million. Within 10 years, the number had climbed to more than $82 million, coinciding in part with the schools’ decision to jump from the Big 12 to the lucrative SEC. And last year, the school reported a record $107 million.

Most of that money goes to contracts, facilities and other expenses; in fact, the school operated at a slight deficit in 2018. But it also shows how big the stakes have become in major college sports.

No wonder schools come out swinging rather than capitulate to the NCAA.

“I never noticed money was ever a problem when a major university was defending an infractions case,” said David Swank, the dean emeritus of the University of Oklahoma law school and a past chair of the NCAA’s committee on infractions. “If it was one of the smaller colleges or universities, that may have been a problem, but it was not one that was ever argued before my infraction committee.”

The NCAA’s so-called death penalty is still on the books but has not been given out since it was used against SMU’s football program in the late 1980s. The school had its entire 1987 season canceled and all home games in 1988 following repeated violations that included cash payments to numerous players. The second season was later canceled when so many players transferred it made playing impossible.

Once the penalties expired, the Mustangs’ program was so crippled that it had one winning season in the next 20 years. They did not return to a bowl game until 2009.

The response in the SMU case was nothing like the way schools close ranks three decades later.

“No one really wants to punish a school like SMU because, in this day and age, it affects everyone. There would be lawsuits a mile long,” Ridpath said. “That’s why I tend to view NCAA punishments largely as window dressing, and that may happen with Kansas. I think time will tell.”

In the meantime, the Jayhawks open the season with another loaded roster and national championship aspirations. They will turn their focus back to the basketball court — rather than the legal courts — as their case winds through the NCAA system. Kansas has vowed to fight as long as it takes.

“There is still a story that hasn’t been told, and that would be our story,” Self said. “That will be told in a way that is consistent with the NCAA process, and when it’s the right timing to do that and the public will be aware of that, I very much look forward to that day.”