Designing for dining: Tablescapes from Napoleon til now

NEW YORK — From the age of Napoleon to Depression-era America and beyond, often-unsung designers have brought life to the dining-room table.

NEW YORK — From the age of Napoleon to Depression-era America and beyond, often-unsung designers have brought life to the dining-room table.

“I thought all tablecloths a bore — particularly white,” wrote Marguerita Mergentime, who gained renown for her tablecloth designs during the Depression. “What people needed, I decided, was bold dashing color on the table, a new kind of design that you couldn’t resist.”

She was hardly alone in her quest to create “tablescapes” with a bit of pizazz, according to a new exhibit at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum that explores the impact of design on the rituals and customs of dining. “Tablescapes: Designs for Dining” opened Oct. 5 and will remain on view through April 14, 2019.

The highlight of the show is an elaborate “surtout de table” centerpiece designed for Napoleon Bonaparte, who is believed to have commissioned it as a wedding gift for his stepson. On view for the first time in 30 years and newly conserved, it exemplifies how dining at the highest levels of wealth and power in 19th century France was a theatrical performance, bringing architecture to the tabletop in elaborate vessels for food.

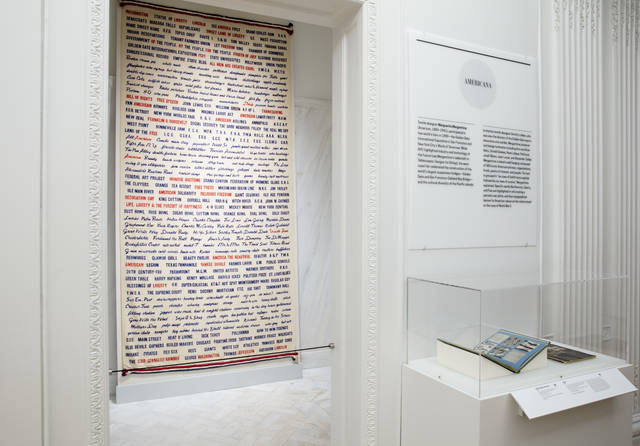

At the opposite end of the design spectrum are Mergentime’s casual, Depression-era table linens, featuring bold colors and a fascination with typography and American history.

Then there’s a futuristic work commissioned by 2017 National Design Award winners Joe Doucet and Mary Ping that envisions a tabletop in a world where population growth has put a premium on space in kitchens and dining areas, and sustainability is crucial.

“From awe-inspiring grandeur to vernacular wit to an emphasis on sustainability, the exhibition provokes a spirited conversation around design’s role in the evolution of a universal ritual,” says Caroline Baumann, director of the museum.

Matilda McQuaid, deputy curatorial director, adds, “We wanted to show how much has changed over time, but also how some aspects have stayed the same.”

The show, divided into three galleries, begins with Doucet and Ping’s work, “The Concentric and Decentric Tables and Seating.”

The moveable structure features two Lazy Susans and built-in stools that can be folded in to seat a small group, or expanded out to accommodate eight people. The terrazzo-patterned surface, reminiscent of stone, is made from recycled food packaging. A close look reveals tiny bits of the Starbucks logo among the tight swirls of gray and green. On the amoeba-shaped dining surfaces, Doucet designed sleek, multi-functional dishes meant to go directly from stovetop to tabletop to fridge, along with a sleek set of cutlery (including matching chopsticks). All his pieces are 3-D-printed for greater customization.

“The future doesn’t have to be dystopian,” says Ping.

In the next gallery is the French centerpiece, created in 1805 by Pierre-Philippe Thomire, a Parisian sculptor known for creating gilt-bronze objects. Made in sections to accommodate a variety of table sizes, the centerpiece is raised slightly above the dining surface and covered in gold with a mirrored base. It resembles a sort of Versailles garden for the table, complete with elegant statuettes and fountain-like towers meant to hold beautifully arranged treats.

The mirrored plateau and gilt-bronze surfaces would have reflected candlelight, and an actual audience seated alongside the table watched as diners ate. The centerpiece is put in context by other works in the gallery, including a drawing of a late 18th century centerpiece inspired by the ruins of Pompeii, and an ornate, blackened bronze clock of the era.

The exhibit then shifts toward equally exuberant but decidedly more humble table decor with Mergentime’s work. The American designer is best known for her bright modernist tablecloths and napkins from 1934 until her death in 1941. They were highlighted in popular magazines of the time and sold in upscale department stores.

“They are really about the communal side of dining, and many of them are designed to be conversation starters,” says McQuaid.

Stylish and witty, many of Mergentime’s pieces feature quizzes or other conversation starters. The 1939 tablecloth “Food Quiz,” for example, includes the printed phrase: “Do you dish the dirt before you dish the soup?”