Saving a language

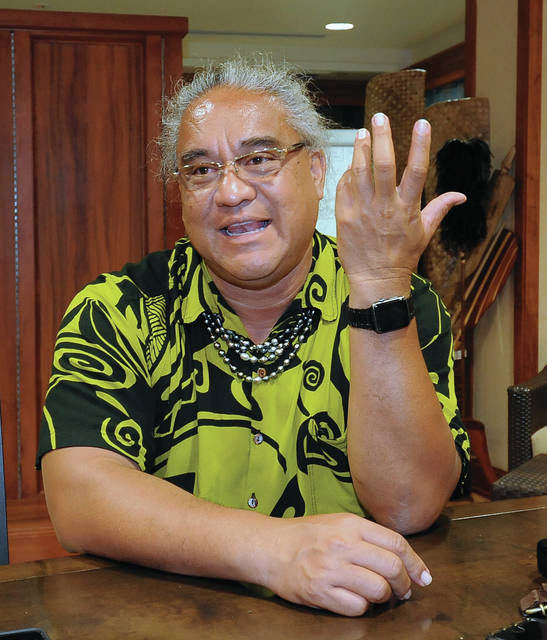

Kumu Keala Ching talks about Hawaiian language classes. (Laura Ruminski/West Hawaii Today)

KAILUA-KONA — It wasn’t so long ago that studying the Hawaiian language, ’olelo Hawai’i, wasn’t a widely encouraged undertaking.

KAILUA-KONA — It wasn’t so long ago that studying the Hawaiian language, ’olelo Hawai’i, wasn’t a widely encouraged undertaking.

For kumu Keala Ching, he remembers that attitude prevailing as recently as his parents’ generation.

“They grew up knowing that there was nothing, nothing to be learned, nothing to be held onto, nothing to be grasped, no rhyme to reason to learn the language,” he said. “Everything was English. Their names changed to a Christian, English name. They lived their life having no connection to the land, no connection to the culture itself. I think for them, what was close culture was family.”

The language had been suppressed for decades, with an 1896 law that banned education through Hawaiian widely seen as a pivotal part of the language’s decline.

Like a fan to a glowing ember however, educators and advocates have in recent decades rallied to the language’s cause. In 1983, a team of educators met on Kaua’i to discuss the language’s dire shape, a meeting that led to the formation of Aha Punana Leo, a nonprofit organization dedicated to revitalizing the language, according to a timeline on that group’s website.

More than 35 years later, the efforts are bearing fruit.

“We have more language speakers today than we ever had back 20, 30 years ago,” said Ching, who is the co-founder and executive director of Na Wai Iwi Ola Foundation, a nonprofit focused on perpetuating Hawaiian culture and practice, including hula and the language.

Today, shoppers in grocery stores pass by signs for “’apala” and “’alani” (apples and oranges) in the produce aisle toward a dairy department advertising “waiu,” or milk. Meanwhile, it’s not uncommon for a conversation on the street to end with a friendly “A hui hou!”

“There’s more awareness, I believe, and effort, I believe, in using Hawaiian as much as we know and can,” said Namaka Rawlins, director of strategic partnerships and collaboration at ’Aha Punana Leo and a former executive director of the nonprofit. “You’re hearing ‘mahalo’ all over — we’ve always heard that, but now it’s just a normalized way. Why not say ‘mahalo?’”

She pointed to words like “aloha,” which has become recognized as “the greeting that we say to each other here in Hawaii.”

“And every time we use a Hawaiian word, it helps to keep it alive,” she said. “And increasing word-by-word in the context and using it in that way, it can only help to support keeping an identifiable Hawaii as our own special place here in the Pacific and the world.”

More opportunities to learn

Advocates’ efforts are bearing out in the numbers as well. In 1983, a study filed as part of a federal report estimated that outside of one small native-speaking community on Ni’ihau, there were fewer than 2,000 native speakers throughout the state, all of them over 60. A state report from 2016, by contrast, counted more than 18,000 people across the state speaking Hawaiian at home, nearly 6,000 of them in Hawaii County.

And opportunities abound throughout the community for those looking to get some experience with the language — from preschool immersion programs to courses geared toward adults trying to either reconnect with their roots or gain a deeper understanding of the islands where they’ve made their home.

Mobile app developers are seeing an opportunity to get involved too, partnering with organizations and experts in the state to get Hawaiian courses into people’s pockets on their smartphones. But while some local educators welcome these modern-day tools, they also caution that real understanding and education takes more than an app.

This month, Duolingo, a company that counts more than 300 million learners, launched its own Hawaiian course, which it developed in partnership with Kamehameha Schools and Kanaeokana, a network of schools and other organizations advocating for Hawaiian education. As of Sunday, the course counted close to 55,000 active learners.

Duolingo joins other applications like Drops, which announced its course this September, and Mango Languages, which announced its Hawaiian course in 2011.

A chance to contribute

Duolingo lead community specialist Myra Awodey said at first glance, a Hawaiian course might seem niche for a company with a user base counting in the hundreds of millions.

“On the other hand,” she said, “I think we’ve realized that we’re in the unique position to be able to access not only a linguistic ‘time capsule’ to preserve endangered languages, but facilitate the spread of shrinking languages.”

Duolingo isn’t the only one recognizing an opportunity to take part in saving endangered languages.

Acknowledging the “incredible preservation efforts” already underway locally, Drops co-founder and CEO Daniel Farkas said the company wanted to get involved and support revitalization of the language.

“My first language is Hungarian, and I’ve seen the rise and fall of many niche languages (including my own),” said Farkas. “I fell in love with the beauty of Hawaiian, and knew how much of the culture and history is associated with the language.”

Each app takes a different approach to language learning. At Drops, the main focus is vocabulary.

Users learn one word or “drop” at a time, consisting of an illustration (e.g. bamboo) and word (i.e. “’ohe”). Users practice their skills through word puzzles, collecting new words as they go, with categories from “essentials” like “a hui hou” to “local Hawaiian words” like “humuhumunukunukuapua’a.”

“When we made the decision to offer Hawaiian, we knew we had to do it right,” said Farkas. “To us, that meant offering words that hold specific cultural significance.”

Mango’s approach uses vocabulary and structures while also focuses on “metalinguistic awareness,” said content development manager Anja Green, encouraging users to develop a deeper comprehension of the language’s form.

How it works

Green referenced one of the app’s features, “voice compare,” which lets users record themselves speaking Hawaiian and then play it back and compare it to a native speaker’s pronunciation.

Pronouncers, she added, are vetted native speakers, and the company looks for speakers who have “retained excellent accents in their native language.”

The company has also partnered with more than 2,280 libraries globally, including the Hawaii State Public Library System, to give patrons access to Mango courses. State library card holders have full access to more than 72 language courses from the company through its website, www.MangoLanguages.com.

And at Duolingo, Awodey said, the focus is on getting people talking.

“We want you to be able to communicate as much as possible as soon as possible,” Awodey said.

That means skipping over lessons explicitly focused on grammar in favor of useful phrases and words people can use in conversation.

“Whether you’re visiting Hawaii or reconnecting with your heritage, we want you to be able to talk about your family,” she said. “We want you to be able to ask for directions, maybe bargain or find out how much something costs. So we really focus on the vocabulary that is the most useful.”

Course students begin with an “intro” skill, which teaches basic phrases and sentences like “Yes” and “No, thank you.” Completing skills unlocks new ones on the tree, such as “’ohana” and “weather.”

Island real-life learning

But with this latest way of teaching getting into everyone’s pockets, educators caution that while they hadn’t had much experience with the newest apps on the market themselves, apps can only take students so far, saying learning Hawaiian is much more than memorizing words and phrases.

Kaho’okahi Kanuha, a sixth- and seventh-grade teacher at Hawaiian language immersion school Ke Kula ’o ’Ehunuikaimalino, said while he’s not opposed to the apps, he’s also not a big advocate for them.

“I’m not trying to teach a language, I’m trying to save a language,” he said.

In order to do that, he said, apps can’t be the primary place people are learning and engaging with the language, saying normalization requires that people speak and use Hawaiian among themselves. If they don’t, the language won’t survive.

“And so if we go ahead and learn words and memorize words, and we memorize songs, but that’s the fullest extent to which we take it, then we’re not really — in my opinion — not really contributing towards the language normalization and revitalization,” he said. “We’re kind of putting a cap on it by making it something that’s more ornamental rather than useful and practical.”

Awodey doesn’t disagree, saying Duolingo is one tool among many.

“It’s pretty clear that the best way to learn a language is to talk to a native speaker,” she said, and Duolingo neither could nor is trying to replace language teachers.

Instead, she said, it’s an opportunity for students to practice on their own to get as much as they can out of face-to-face interactions with an instructor.

Speaking English with Hawaiian words

And then there are the more abstract aspects of language that only come with a critical understanding of the language itself — not just idioms but the cultural collective of stories recorded on tape, printed on page or passed down through time.

“That’s where the language truly lives,” Kanuha said. “And that’s where you truly get a glimpse and a feeling for what the language is about, what it used to be, what it should be, what it can be.”

Without that foundation for learning, he said, “you become someone who speaks English using Hawaiian words.”

As people learn a new language through the lens of their native tongue, he said, they naturally take their English habits with them when they start studying and speaking Hawaiian.

“But it’s only through engaging with others who are a little bit more knowledgeable than us, who are a little bit more skilled than us in language use,” he said, “it’s only through reading the mo’olelo — the stories — and the writings of our kupuna and listening to their tapes that we can really realize and see just how different we are from them.”

Ching said when those foundations aren’t included, that’s where some problems come in.

“Because many of us didn’t have a chance to grow up with our elders that really lived the culture, many language speakers gained the language without the relationship to the elders,” Ching said, “which means a lot of them are just speaking with no cultural relevance.”

And that, he said, “is a big worry.”

“Because we want to be able to speak with relevance of what the old people had in store for us,” he said.

Ching said he believes language apps are getting better, particularly because of the inclusion of Hawaiian speakers and pronouncers in the development process.

“The language is an oral language, so you need someone to actually puana — to pronounce — the words, versus having Siri try and pronounce these words and you get the pronunciation all wrong.”

But a critical part of that is clear and accurate pronunciation.

“And you can only get that when you really practice to really hear and key on to pronunciation,” he said. “The ’okina-less, the ’okina-plus, those words are the ones that get really, really mispronounced. And so on the app, they’re not quite there yet.”

And it’s not just pronunciation, but also facial movements, he said. What he’d like to see, he said, is the inclusion of video vignettes to help with teaching the language.

Overall, local educators said the fact companies are taking an interest in Hawaiian is a good sign for the language’s momentum.

For Rawlins, it’s a sign that tech-savvy generations are using modern tools and platforms to help people learn, which is great not just for promoting Hawaiian but other endangered languages as well.

And for Kanuha, the development of these language courses demonstrates that there’s interest and value in promoting education in the language.

“For someone to put time, money, effort, resources into something means that they find value in it and they see it worth being preserved or progressed,” he said.

More opportunities, he said, creates more awareness and understanding about the language and the historical context around it. And with that, he said, will come a consciousness that continues to fuel the revitalization movement.

Looking to the future

Forty years into the push to revitalize the language, Kanuha said the journey toward normalization throughout the islands is “still at the very infant stages,” and, given that it took a long time to push the language out, it’ll take a long time to bring it back.

“But we can’t get complacent in the length and the time of this movement,” he said. “We have to stay vigilant, we have to stay active, and we’ve got to keep progressing and moving forward.”

Ching said he hopes that’s the direction things are going in.

“I think it’s a good thing that we can learn the language and hope that we can gain an understanding of the culture,” he said. “I don’t think it’s moving fast enough, but I think it’s moving in the right direction, which is good.”

And from Rawlins’ perspective, everyone who’s in a position to use and promote Hawaiian throughout the community is doing their part, which is exactly what it’ll take — “Everybody kokua,” she said.

In addition to a responsibility to sustaining, for example, the environment, she said, there’s a responsibility to the language too.

“That’s a strength for us here in Hawaii, that we have an identifiable language,” she said. “It belongs only here. It lives here; this is its home, its place on Earth, and we have our place names, and we have our mountains and we have all that surrounds us. It just exudes our Hawaii and our place.”

Ching, thinking back to when he told his father that he wanted to pursue the language, recalled his father’s response:

“‘What?’” his father replied, “‘What are you going to learn the language for? The language is not gonna take you nowhere! Don’t learn the language!’”

“And I learned the language, and my world opened up,” Ching said. “And my father is now so proud.”

As a descendant of immigrants, I’m strongly in favor of keeping your heritage alive — but don’t use it as an excuse to exclude other heritages. Just because someone doesn’t have the same genetic ancestry you do, doesn’t mean they don’t like/admire/want to imitate your heritage!

“an 1896 law that banned education through Hawaiian” not exactly accurate.

After 10 of thousands of immigrants were brought here by the King’s Board of Immigration from Japan, China, South America (Portuguese), and else where the public school system was in a mess, a real Tower of Babel. So it was decided to teach all children in English. This had actually been called for by the Kings since 1855.

Polynesian-Hawaiian was not “outlawed” any more than any other language except that the language of instruction in the public schools would be in English.

As today, English must be stressed first and foremost for best long term life skills results. After all, English is spoken everywhere in the world, and Polynesian-Hawaiian is spoken no where else.

Hawaiian Immersion Schools are already proving poor results later in higher education with higher drop out rates when these students must be able to read and write English well.

Learning different languages is good, but concentrating on English first is the key.

Not true, Hawaiian was indeed outlawed. Not just outlawed, but the law was violently enforced. Many members of my family recall hearing other languages being spoken in school. But if they were caught speaking Hawaiian they would be beaten and even removed from the school. The law wasn’t rescinded till the mid 1970’s. But based on your negative “thoughts” of Hawaiians and their immersion schools, you’re no different then the people who beat my family members.

I can hear the hate you have for Hawaiians in your words. The university of Hawaii is full of doctorates and graduates of the immersion program. Most of the dropouts in Hawaii come from the English speaking programs. Instead of spewing lies and attacking people you’ve already spent over a century trying to destroy show some self control and support for their efforts in rebuilding what your ancestors tried and failed to destroy.

e ola ka ʻōlelo hawaiʻi

That’s cool, it certainly should be preserved, but probably as a primary language, outside of a native lifestyle community, it’s pretty much archaic. I mean, there’s no Hawaiian word for “quad core ninth generation CPU”, or “methyl mercury”. If 90% of the words you need in business are English, there’s not much hope for a pre-industrial language like that.

People pretty much end up using what’s convenient, for example, I now call the Pacific Golden Plover a “kolea”, in fact, I just had to look up the English words, I had forgotten. But I don’t use “aloha” and “mahalo”, because, well . . . they sound touristy coming out of a haole’s mouth.

“After all, English is spoken everywhere in the world” not exactly accurate.