HILO — Because so much of Hawaii Island geography is designated as lava zones 1 and 2, it doesn’t make sense to bar construction there, Mayor Harry Kim said Tuesday.

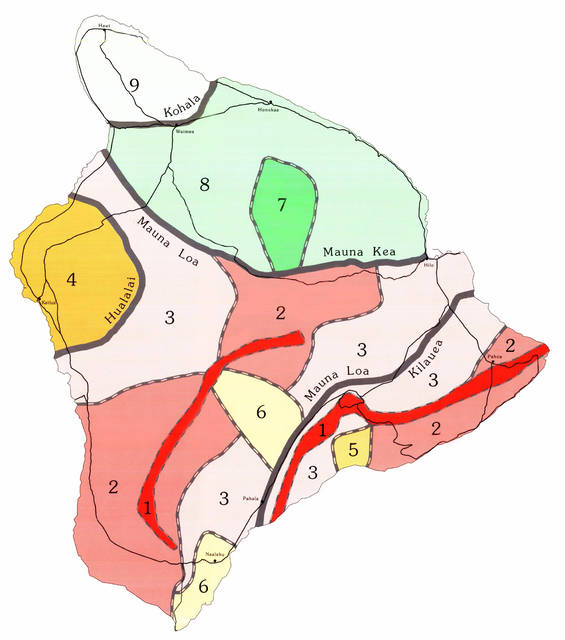

Kim, reacting to public statements by state officials, said construction can’t be restricted in those two zones with the highest risk of inundation without compensating property owners for the loss of use of their lands. Lava zone 2, for example, includes a large swath of Puna and most of southwest Hawaii Island, including Hawaiian Ocean View Estates, considered the largest private subdivision in the nation, with 11,500 1-acre lots over 18 square miles.

“These are our bedroom communities. A lot of people purchase there because they want to live there, but a lot of people live there because that’s the only place they can afford,” Kim said after a County Council briefing of short- and long-term plans for housing in the midst of an eruption in lower Puna.

Instead, Kim said, his administration can, and will, deny rezoning to higher density developments in those two lava zones. Recommendations on rezoning applications are made to the planning commissions by the planning director, which then forward their recommendation to the County Council.

“I wish there was a simple answer,” Kim said, noting that the lava-flow hazard zones were set by the U.S. Geological Survey in the 1980s, while the subdivisions were created in the 1950s and ’60s.

Gubernatorial front-runners incumbent Gov. David Ige and challenger U.S. Rep. Colleen Hanabusa, as well as incumbent District 4 state Sen. Lorraine Inouye, all Democrats, in recent political forums have advocated construction restrictions in the lava zones most at risk.

The County Council heard from department heads explaining the process of creating emergency, short-term and long-term housing for residents of the 700-plus homes that have been destroyed and another 15 made inaccessible since lava started flowing across lower Puna on May 3.

There are still 219 people in shelters in Pahoa and Keaau, where there was at one time a high of 485, said Parks and Recreation Director Roxcie Waltjen. The evacuees are being interviewed through today to determine what are the barriers to them moving into more long-term shelters. The number of tents at the Pahoa site have dwindled by half, she said.

The county is working with the Federal Emergency Management Agency for intermediate housing solutions. Some 2,000 people have registered with FEMA for some kind of assistance, said Executive Assistant Roy Takemoto.

Working with faith-based and nonprofit organizations, the county has seen 20 transitional micro houses built with 20 more on the way, with another 50 being planned in Pahoa, he said. The county is also scouting out areas for more housing, such as near the Panaewa equestrian center.

The county is looking at a number of options for housing during the 18 months that FEMA provides assistance, Takemoto said. With FEMA paying 75 percent to the county’s 25 percent, options include hotels, allowing accessory dwelling units such as ohana structures, refurbishing public housing units that currently stand vacant and working with the real estate industry to identify the housing inventory available for rentals and ownership, he said.

Takemoto said the county is also looking into creating a redevelopment agency and revising the tax code to make federal Section 8 vouchers and county affordable housing more attractive to landowners, especially in West Hawaii.

While tragic, the lava inundation offers the county a unique opportunity to create communities from scratch, planning officials said. Creating walkable town centers at subdivisions with transit hubs and schools, creating agricultural parks with clustered housing, infrastructure and shared processing facilities are among the long-term possibilities.

Puna Councilwoman Eileen O’Hara, who represents the district hardest hit by lava, wanted more specifics on propping up local businesses and building more housing.

O’Hara said her district needs something more concrete than “just nice imagery of walkable towns.”

“Recovery isn’t just about housing. It’s also about rebuilding the district,” O’Hara said.

It still takes nine to 12 months to get a building permit, she said. The district needs economic development measures such as lava observation platforms or tour buses, she said.

“We have lost tons of jobs,” she said. “We’ve got to move a little faster to address the needs of the folks who are impacted by this.”