Future of Saipan visa program in question amid labor abuses

HONOLULU — A push to save and expand a visa program unique to the Northern Mariana Islands is hitting skids after recent cases of labor abuse and visa fraud, delivering a major blow to the U.S. commonwealth’s economy, which relies heavily on foreign workers.

HONOLULU — A push to save and expand a visa program unique to the Northern Mariana Islands is hitting skids after recent cases of labor abuse and visa fraud, delivering a major blow to the U.S. commonwealth’s economy, which relies heavily on foreign workers.

The visa classification, known as CW-1, allows employers to seek permission to hire foreign workers and is aimed at alleviating a labor shortage among the Pacific islands’ population of roughly 52,000. The program was launched about a decade ago and has brought in nurses, teachers, hotel maids, bakers and more.

But a recent spate of visa abuses in the Northern Mariana Islands has cast a shadow over efforts to bolster the program, due to sunset next year.

Just this month, labor authorities reached a $14 million settlement with Chinese companies for exploiting a visa waiver loophole to bring in illegal workers. And a local businessman and two associates were convicted in federal court for their role in a scheme to defraud foreigners by promising them U.S. jobs and green cards in exchange for cash.

“Seen from the distance of Washington, D.C., this looks like a program that doesn’t deserve to be continued — it’s not being properly monitored for abuse,” said Bruce Mailman, an attorney at Mailman & Kara in Saipan who has worked with companies employing workers on the CW-1 visa. Still, “it’s a critical program for this place.”

Only 4,999 visas have been allotted for 2019, half of what was available the previous year.

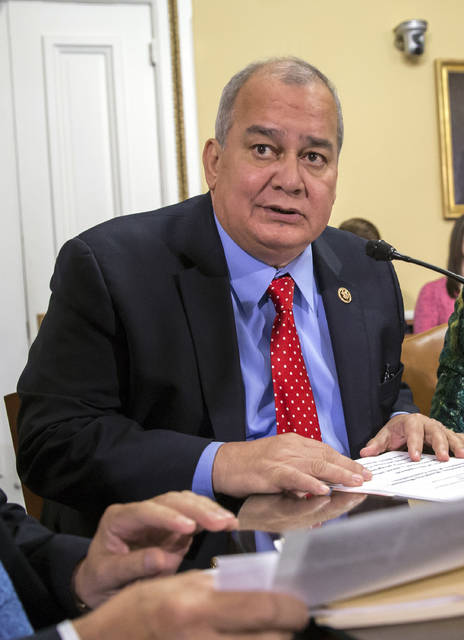

Cutting the number of visas threatens jobs and hurts the Marianas economy, Rep. Gregorio Sablan, a Democrat representing the islands, said in a March 23 statement. He also has said recent violations of U.S. law give the Marianas a black eye and make it increasingly challenging to maintain a sufficient workforce.

A bill introduced in January by Sablan and U.S. Sen. Lisa Murkowski, an Alaska Republican who recently visited the islands, seeks to extend the program for another decade. It would increase the number of visas allotted and crack down on oversight.

Provisions to defend against labor abuses include allowing only “legitimate businesses” to be approved for permits — defined as firms that comply with wage laws and safety regulations for at least five years. Companies cannot engage in illegal activities, such as human trafficking, according to a version of the bill from March 20. It also reiterates that construction firms are barred from using the program, a change that passed into law last year in a separate bill.

The U.S. Labor Department has found contractors with the Hong Kong firm Imperial Pacific in violation of most of those requirements. Imperial Pacific is building a casino in Saipan, the largest of the Northern Mariana Islands. But construction stalled as thousands of illegal workers returned home to China following an FBI raid after a Chinese man died in a construction accident.

The legislation is on hold as Congress is in recess until April 9. By the time lawmakers are back in session, the government will already be accepting applications for 2019.

Companies have long known the CW-1 program would end but continued to favor the program over other visas because it allows them to pay the local minimum wage. In 2008, when the program was introduced, that was $3.55 an hour, far below federally mandated levels.

But that incentive is disappearing. Incremental changes over the years have raised the visa’s required hourly wage to $7.05, and by this September it will match the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour.

Saipan businesses that rely on the program are scrambling to make changes. Hong Electric Enterprises, an electric supply firm, has brought in employees on CW-1 permits for years and is working to transition some workers to other visas given uncertainty over the program. “We cannot afford to lose key personnel,” said Carol Tamparong, a Hong Electric manager who originally came on a permit.

Employers could consider visas including the H-1B for skilled workers or the H-2B for seasonal work, as a federal cap that applies in other states doesn’t apply to the Northern Mariana Islands, given the local labor shortage, said Janet King, an immigration attorney in Saipan. Other visas, like the EB-3, which cover a range of jobs from accounting clerks to architects, also confer visa applicants more rights and a path toward a green card.

By comparison, a CW-1 visa applies only within the commonwealth and doesn’t allow the holder to travel or work elsewhere in the U.S.

More than half of the Northern Mariana Islands’ workforce is from China, the Philippines and elsewhere, filling 80 percent of all construction and hospitality jobs.

Without those workers, the commonwealth’s economy would have clocked as much as a 62 percent reduction in 2015, according to a May report by the Government Accountability Office.

Demand for the CW-1 program exceeded the number of available permits for the first time in 2016, and the report predicted a labor shortage given plans for additional hotels, casinos and other projects that would require thousands of employees.

Foreign workers are vital to the islands, Mailman said.

“Because of our distance from the U.S. mainland, it’s kind of hard to entice people to come out here for jobs that pay below the scale for what they’re used to, despite being a tropical paradise,” he said.