HONOLULU — The state of Hawaii on Thursday released an audio recording of the drill it was running in January when an employee mistakenly sent cellphone and broadcast alerts warning of a ballistic missile attack.

But the 24-second recording the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency released was heavily redacted.

It started with the words “exercise, exercise, exercise,” followed by a prolonged beep, then the phrase “this is not a drill” and another prolonged beep. It ended with “exercise, exercise, exercise.”

Spokesman Lt. Col. Charles Anthony said the agency could only disclose a small portion of the recording because the U.S. Pacific Command would use the exact same or very similar language if it notified the agency of an actual missile threat.

“Somebody could use that verbiage to compose a message then call the state warning point and try to spoof state warning point into thinking there was a real missile alert,” Anthony said.

He said this could be a prankster, North Korea or “something in between.”

The recording isn’t classified, but the material is so sensitive that the emergency management agency treats it like it is, Anthony said.

But Brian Black, the executive director of the Civil Beat Law Center for the Public Interest, said it’s troubling that the agency is only releasing portions that support their narrative of what happened.

The employee who sent the alert has said he didn’t hear the word “exercise” spoken during the drill and thought the threat was real. The agency has since fired him.

“The level of public disagreement about this issue raises the interest in this such that they really should have come forward with more and they really should have been more forthcoming about what it was that happened,” Black said.

Black said it sounds like the agency is saying it has no way of verifying the message is coming from Pacific Command other than the language that’s being used.

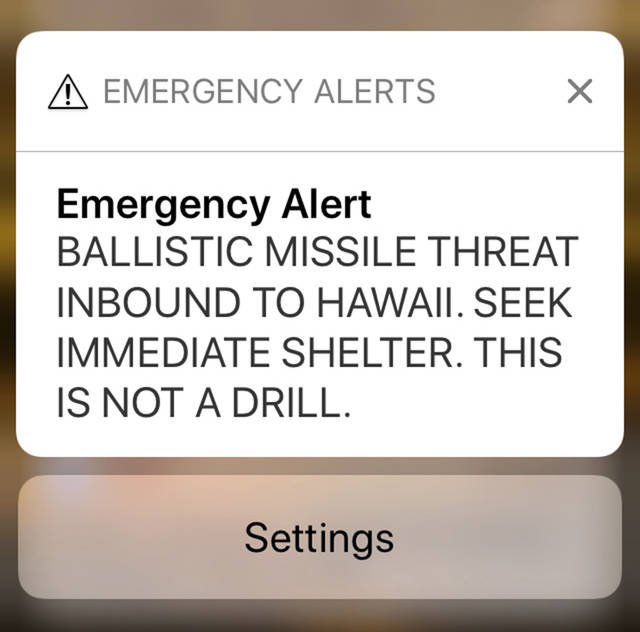

The agency’s action on Jan. 13 sent push alerts to the cellphones of thousands of Hawaii residents and visitors. Many panicked, fearing they were about to die in a nuclear attack. It took the agency 38 minutes to send another cellphone and broadcast message notifying the public the alert was sent in error.

Ralph Cossa, president of the Pacific Forum CSIS think tank in Honolulu, said he understands the state’s need to be cautious and is “quasi-sympathetic” to its position on the redactions.

“You don’t want your procedures so clearly spelled out that somebody who could hack in the future could duplicate it and send out send out a very realistic message that could then create panic once again,” he said. There are people “both capable and inclined” to do such things today, he said.

“On the other hand, if that’s all they put out, it certainly will raise more suspicions than it will answer questions,” he said. Common ground should be found closer to being more transparent than Thursday’s release, he said.

Cossa said he hopes there would be procedures in place to verify future messages from the Pacific Command and the messages would adopt some new wording.