Pahoehoe lava flows are a common feature on Hawaiian volcanoes, and they have been a serious hazard to residential areas during the Puu Oo eruption over the past few decades. Pahoehoe destroyed much of the town of Kalapana, buried most of the Royal Gardens subdivision, and most recently threatened the town of Pahoa.

A challenge with pahoehoe flows is that they are difficult to track and forecast, in large part owing to how they spread out on the ground. As the surface of a pahoehoe lava flow cools, lava tubes can develop and transport lava beneath the flow surface. This lava emerges at the active flow front, and on the flow surface in “breakouts” from the tube system. These lava breakouts can occur in many different areas along the length of a flow at any given time. On Kilauea, lava breakouts are often scattered over areas spanning miles.

The scattered nature of breakouts is the main challenge for monitoring and forecasting pahoehoe flows. In some ways, monitoring pahoehoe flows can be much more difficult than monitoring aa flows, which are often focused in a single, well-defined lava channel.

Until recently, geologists at the U.S. Geological Survey’s Hawaiian Volcano Observatory could only effectively map the margins of a pahoehoe flow. The advance and expansion of the flow margins provided a picture of evolving behavior at the edge of the flow (and potential hazard), but it was difficult to map out exactly where all the breakouts on the flow surface were located.

These breakouts are commonly positioned well away from the flow front and margins. Sometimes they advance to reach the flow margins, and drive the flow in a new direction. Knowing where breakouts are clustered, and how they are evolving, is valuable for anticipating where the advance of a pahoehoe flow might become focused.

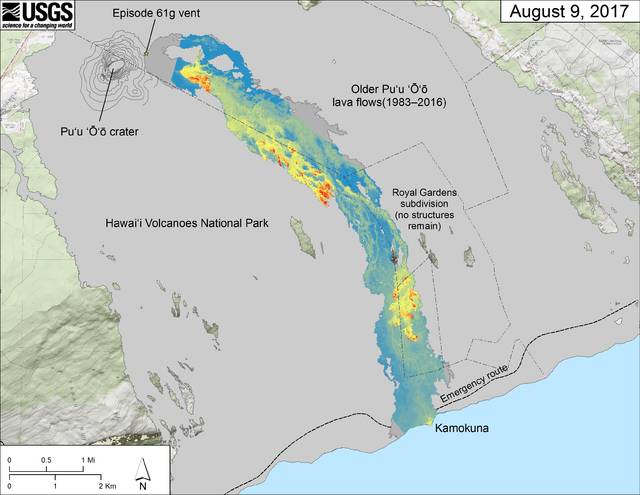

Over the past few years, HVO geologists developed a new technique to map activity across the entire surface of a pahoehoe flow. During our routine helicopter overflights, we use a handheld thermal camera to collect a series of overlapping, oblique images along the entire length of the lava flow, from the vent to the ocean entry. We then use “structure-from-motion” computer software to stitch the individual images into a large mosaic.

This type of software uses the overlapping images to calculate the exact 3-D position of each image pixel on the surface of the Earth. We insert a handful of known coordinates in the image mosaic as “ground control” points, which provide “georeference” for the mosaic and orients it to its correct position on the Earth’s surface.

This mosaic of thermal images is basically a thermal map of the lava flow surface, and reveals the exact location of all the active surface breakouts. The map provides a highly accurate picture of surface activity, improving our ability to anticipate where lava might advance. The added benefit is that we can precisely map the path of the main lava tube, which produces a subtle line of warm temperatures on the surface.

Structure-from-motion software has become much more accessible in the past five to 10 years, and geologists around the world use it to make accurate 3-D ground surface models. This software is another example of how rapidly technology is changing. It also shows how new techniques can overcome long-standing challenges and improve our ability to monitor Hawaiian volcanoes.

Volcano Watch is a weekly article and activity update written by U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory scientists.

Visit https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/hvo for past Volcano Watch articles, volcano updates and photos, recent earthquake info, and more. Call for summary updates at 967-8862 (Kilauea) or 967-8866 (Mauna Loa). Email questions to askHVO@usgs.gov.

Volcano Activity Updates

This past week, Kilauea Volcano’s summit lava lake level fluctuated with summit inflation and deflation and ranged about 75-141 feet below the vent rim. On the East Rift Zone, the 61g flow remained active, with lava entering the ocean near Kamokuna and surface breakouts downslope of Puu Oo. Widening cracks and slumping on the Kamokuna lava delta indicate its instability and potential for collapse. The 61g flows do not pose an immediate threat to nearby communities.

Mauna Loa is not erupting. During the past week, small-magnitude earthquakes continued to occur beneath the summit caldera and upper Southwest Rift Zone, primarily at depths less than 3 miles, with some additional deeper events, 3-8 miles. GPS measurements continue to show deformation related to inflation of a magma reservoir beneath the summit and upper Southwest Rift Zone. No significant changes in volcanic gas emissions were measured.

One earthquake with three or more felt reports occurred in the islands during the past week. At 8:40 p.m. on Sept. 15, a magnitude-3.7 earthquake occurred 21 miles northeast of Kaneohe, Oahu, at a depth of 6 miles.