WASHINGTON — Emboldened by a business-friendly president, Republicans in Congress have set a goal that is nothing if not ambitious: To undo the stricter banking rules that took effect after the devastating 2008 financial crisis.

WASHINGTON — Emboldened by a business-friendly president, Republicans in Congress have set a goal that is nothing if not ambitious: To undo the stricter banking rules that took effect after the devastating 2008 financial crisis.

A vote Thursday to approve the bill in the House is essentially assured. The landscape is far different in the Senate, where Democrats have the votes to block it.

The 2010 Dodd-Frank law imposed the stiffest restrictions on big financial companies since the Great Depression. It curbed many banking practices and expanded consumer protections to restrain reckless practices and prevent a repeat of the 2008 meltdown.

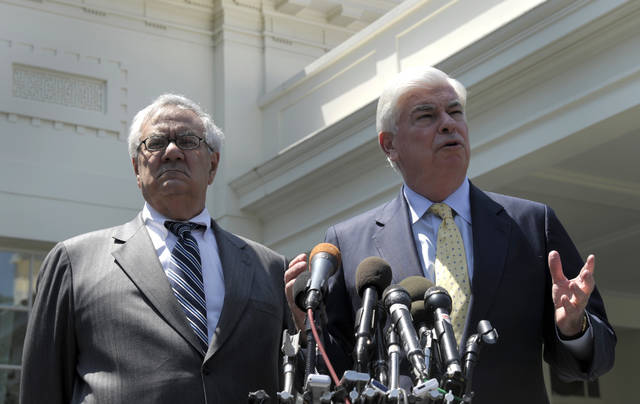

The House bill, pushed by Rep. Jeb Hensarling, the Texas Republican who leads the Financial Services Committee, would repeal about 40 of Dodd-Frank’s provisions. Notably, it would sharply diminish the authority of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which oversees the practices of companies that provide products and services from credit cards and payday loans to mortgages and debt collection.

President Donald Trump launched his attack on Dodd-Frank after taking office, ordering a Treasury Department review of the complex rules that have put the legislation into practice. Trump called the law a “disaster” whose restrictions have crimped lending, hiring and the overall economy.

One part of Treasury’s review is expected to be released soon. It could provide a blueprint for regulators to rewrite the rules. But Congress’ legislation would be needed to actually revamp the law.

Unwinding a complex law that clocks in at 2,300 pages takes its own hefty bill: The Republicans’ Financial Choice Act, as it’s called, runs 580 pages. Here’s a look at key changes it would make:

———

BANK REGULATION

Under the House bill, banks could qualify for regulatory relief if they held enough capital to cover potential big losses — a 10-1 ratio of capital over borrowed money. In exchange, such banks would gain exemptions or eased requirements for “stress tests” to assess their ability to withstand a downturn and for their plans to reshape themselves if they failed.

During the crisis, the government intervened to rescue the largest banks from collapse and saved some faltering institutions with bailouts and emergency loans or helped sell them to other banks. Trillions of taxpayer dollars were put at risk.

To avoid endangering taxpayers again, Dodd-Frank authorized regulators to dismantle a failing big firm, if they felt its collapse could endanger the entire system, and sell off the pieces. The Treasury would pay the firm’s obligations and be repaid with industry fees and money raised from shareholders, bondholders and asset sales.

Critics argue that that means taxpayers could still end up on the hook. The new legislation would eliminate the regulators’ power to dismantle firms.

———

VOLCKER RULE

This rule, which bars the biggest banks from trading for their own profit, would be repealed. The idea behind the rule was to prevent high-risk trading bets that could imperil federally insured deposits. Some banks argue that the Volcker Rule stifles legitimate trading on behalf of customers and the banks’ ability to hedge against risk.

Republicans have stressed the need for regulatory relief from Dodd-Frank for community banks. And in a fairly rare area of bipartisan agreement, some Democratic lawmakers have indicated support for this, at least in theory.

The legislation would exempt smaller banks from a number of Dodd-Frank requirements. Banks with under $10 billion in assets, for example, would have to run “stress tests”— gauging their ability to withstand a severe economic downturn — just once a year instead of twice.

———

CONSUMER WATCHDOG AGENCY

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau was empowered by Dodd-Frank to scrutinize the practices of virtually any business that sells financial products and services, including for-profit colleges, auto lenders and money-transfer agents.

The legislation would reduce those powers. And it would let the U.S. president remove the CFPB director at will without citing a cause for firing. That’s the subject of a battle now in federal court. No longer would the CFPB have a guaranteed funding stream from the Federal Reserve. Instead, it would depend on Congress for its funding just as most federal agencies do. The agency would also lose its authority to write rules, like those governing mortgages.

The bill’s targeting of the CFPB especially rankles Democrats and consumer advocates. The agency has, among other things, conducted investigations across the spectrum of financial products and opened a database for consumers to lodge complaints against companies. As a result of its enforcement actions, the CFPB says it has recovered nearly $12 billion that it returned to 27 million consumers harmed by illegal practices.

———

REINING IN REGULATORS

Dodd-Frank established a Financial Stability Oversight Council of top regulators, led by the Treasury secretary, of top regulators to monitor the financial system and identify potential threats.

The council also has authority to review nonbank financial firms, like insurance companies, to determine whether they’re so large and interconnected that their failure would threaten the entire system. Once the council deems a company “systemically important,” it becomes subject to stricter rules. Its use of borrowed money is limited. And it must submit to close supervision by the Federal Reserve and make more detailed disclosures.

The new legislation would strip the council of its authority to designate financial firms as systemically important and would make its funding subject to Congress’ budget process.

———

RETIREMENT INVESTORS AND SHAREHOLDER POWER

The legislation would repeal the Obama-era Labor Department’s so-called fiduciary rule. The rule tightened requirements for professionals who advise retirement savers. Wall Street and Republicans have been pushing against the rule, which compels financial pros who charge commissions to put their clients’ best interests first in advising them on retirement investments.

The legislation also targets the frequency of “Say on Pay” shareholder votes on executive compensation as established by Dodd-Frank. Rather than hold a nonbinding vote at least once every three years, the legislation would allow it only when executives’ compensation has changed “materially” from the previous year.

Shareholders with relatively small portions of company stock would find it harder to bring proposals to a vote by all shareholders. Individuals or groups of investors would have to own at least 1 percent of a company’s stock for at least three years to put a proposal on the company proxy ballot. That compares with the current requirement of $2,000 worth of stock for one year.