HONOLULU — The conversation about food security in Hawaii overlooks many details according to University of Hawaii- Manoa scholars Aya Hirata Kimura and Krisnawati Suryanata. ADVERTISING HONOLULU — The conversation about food security in Hawaii overlooks many details according to

HONOLULU — The conversation about food security in Hawaii overlooks many details according to University of Hawaii- Manoa scholars Aya Hirata Kimura and Krisnawati Suryanata.

“We wanted to just kind of redirect our attention and not rush forward to find a solution but to see if our visions are actually the same,” Suryanata said. “Let’s agree on a few goals. Let’s be clear.”

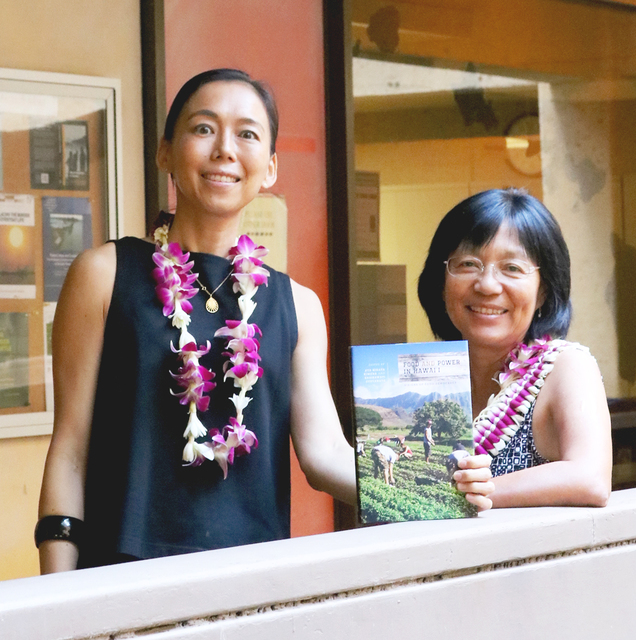

Their recently released book, “Food and Power in Hawaii: Visions of Food Democracy,” is meant to introduce some of the factors intertwined with Gov. David Ige’s goal of doubling local food production by 2030.

“I sympathize with the investments in local food but at the same time I feel the arguments for localization of food are simplistic,” Kimura said.

She continued: “If the goal is maximizing the volume of food in the quickest way, the quickest way to do that is with modernized farming and intensively chemical farming and is that what people want?”

Focusing on the increase of local food production isn’t a sufficient enough goal, they said, and agriculture policy needs to address more than simply the quantity of locally produced food.

“When we’re talking about food democracy, we wanted to pay special attention to the power relations and hierarchies in the food systems,” Kimura said.

The book is a collection of nine essays that show a link between food and public policy making, social activism and culture changes.

“The concept is how to broaden public participation in reshaping our own agriculture system,” Suryanata said.

It discusses issues like race and gender within agriculture, land use policies, and the use of biotechnology. A couple of chapters also look at the connection between food security and home security; addressing the observation that the poor tend to be marginalized and they have less political voice in the system.

“Those power relations need to be front and center when we discuss related policies,” Kimura said. “By talking about food democracy we wanted to pay attention to the power relations in hierarchies in food systems.”

Suryanata added: “When we were editing these different contributions, we saw how each of them added more complexity and more aspects to consider on what to do about our food and agriculture system.”

Farmers’ markets are another area addressed in the book, which asks people to distill the goals of farmers’ markets for those participating.

“Is the goal to sell prepared food or to create a value-added venue for people who are trying to maintain the viability of their farm?” Suryanata said.

When agriculture legislation was formed 50 years ago, the goal was simpler according to Kimura and Suryanata. It was to save agriculture lands from being urbanized and everyone was on the same page.

“Now, in 2016, the goal is multi-layered and that’s what we’re trying to expose in the chapters,” Suryanata said. “If we say, ‘let’s save agriculture,’ wait a minute — what kind of agriculture? For women, for tourists, for local residents, for the poor?”