WASHINGTON — The Environmental Protection Agency had sufficient authority and information to issue an emergency order to protect residents of Flint, Michigan, from lead-contaminated water as early as June 2015 — seven months before it declared an emergency, the EPA’s

WASHINGTON — The Environmental Protection Agency had sufficient authority and information to issue an emergency order to protect residents of Flint, Michigan, from lead-contaminated water as early as June 2015 — seven months before it declared an emergency, the EPA’s inspector general said Thursday.

The Flint crisis should have generated “a greater sense of urgency” at the agency to “intervene when the safety of drinking water is compromised,” Inspector General Arthur Elkins said in an interim report.

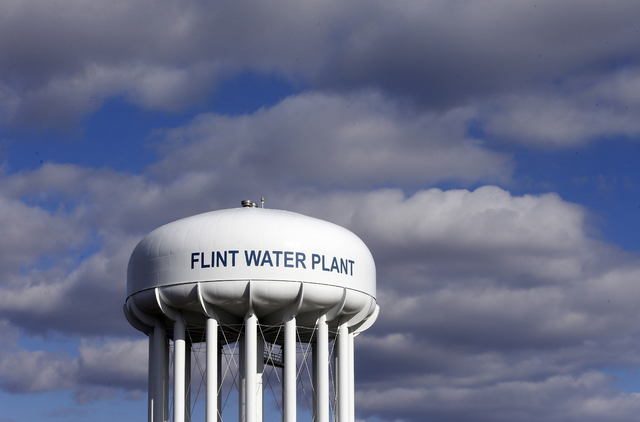

Flint’s drinking water became tainted when the city began drawing from the Flint River in April 2014 to save money. The impoverished city of 100,000 north of Detroit was under state control at the time. Regulators failed to ensure water was treated properly and lead from aging pipes leached into the water supply.

Federal, state and local officials have argued over who’s to blame as the crisis continues to force residents to drink bottled or filtered water. Doctors have detected elevated levels of lead in hundreds of children.

A panel appointed by Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder concluded that the state is “fundamentally accountable” for the lead crisis because of decisions made by state environmental regulators and state-appointed emergency managers who controlled the city.

Even so, Snyder and other Republicans have faulted the EPA for a slow response.

At a congressional hearing this past spring, Snyder blamed career bureaucrats in Washington and Michigan for the crisis, while apologizing for not acting sooner to resolve it.

The report by the inspector general says officials at the EPA’s Midwest region did not issue an emergency order because they concluded that actions taken by the state prevented the EPA from doing so. The report calls that interpretation incorrect and says that under federal law, when state actions are deemed insufficient, “the EPA can and should proceed with an (emergency) order” aimed at “protecting the public in a timely manner.”

Without EPA intervention, “the conditions in Flint persisted, and the state continued to delay taking action to require corrosion control or provide alternative drinking water supplies,” the report said.

Michigan officials declared a public health emergency in October 2015; the EPA declared an emergency three months later.

EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy has acknowledged that her agency should have been more aggressive in testing the water and requiring changes, but said officials “couldn’t get a straight answer” from the state about what was being done in Flint. McCarthy has refused requests by GOP lawmakers to apologize.

“It was not the EPA at the helm when this happened,” she said.

The director of the EPA’s Midwest regional office stepped down Feb. 1 amid withering criticism that the agency failed to act sooner to address lead contamination in the predominantly African-American city.

The official, Susan Hedman, denied wrongdoing, but said she was leaving to avoid becoming a distraction.

In a memo from June 2015, Miguel Del Toral, a scientist in the EPA’s Midwest office, had warned of dangerously high levels of lead. He later criticized the agency for not taking swift action.

Rep. Jason Chaffetz, R-Utah, chairman of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee, said Hedman “dismissed” Del Toral’s warnings without good cause.

“You screwed up and you ruined people’s lives,” Chaffetz told Hedman at a March 15 hearing.