In the chaotic aftermath of World War I in Europe, a small group of enterprising designers, artists and architects — many of them women — stepped forward with groundbreaking ideas for how to improve the quality of life through architecture

In the chaotic aftermath of World War I in Europe, a small group of enterprising designers, artists and architects — many of them women — stepped forward with groundbreaking ideas for how to improve the quality of life through architecture and design.

Their efforts eventually resulted in what is now known as Modernist design, and in many of the conveniences people take for granted today, such as prefabricated houses, open floor plans, and a more pragmatic and streamlined approach to interiors. Materials like Pyrex glassware and linoleum flooring, previously used commercially, were suddenly introduced for domestic settings.

“How Should We Live? Propositions for the Modern Interior,” on view at the Museum of Modern Art through April 23, highlights important yet unsung designers from this pivotal time, from the mid-1920s through the mid-’50s. It takes a closer look at the textiles, crockery, wall coverings and flooring that put iconic Modernist furniture in context.

Rather than focusing on isolated masterworks, the attention is on the interaction of design elements. Visitors are shown designers’ own living spaces, and are invited to explore often-neglected areas of design, like exhibition spaces and promotional displays.

The story begins in Europe, said Juliet Kinchin, a curator in MoMA’s Department of Architecture and Design.

“There was huge social and political disruption following the First World War, and there was a real housing crisis in many parts of Europe that was compounded then by the Great Depression, so architects were really thinking about new ways of living, and how to simplify one’s life and improve the quality of life for masses of people,” said Kinchin, who organized the show with Luke Baker.

The exhibition traces the start of the era to a huge interiors exhibit in Stuttgart, Germany, in 1927, which introduced people to novelties like tubular-steel furniture and prefabricated housing, including the truly contemporary Frankfurt Kitchen, an example of which is featured in the show.

In post-war Frankfurt, about 15,000 prefabricated modular housing units were built in just five years, and 10,000 of them featured one of several versions of the Frankfurt Kitchen. It was designed like a tiny but highly efficient factory, complete with a fold-down ironing board, pull-out cutting board, gas stove, swivel stool, pull-out aluminum storage bins, garbage drawer, draining board and built-in broom closet and cupboard.

The design was by architect Grete Schutte-Lihotzky, the first woman to qualify as an architect in Austria, and it is the earliest work by a female architect in MoMA’s collection, Kinchin said.

“She was designing for single working women and working families, and was part of a democratizing impulse in Modernism to take advantage of new materials and new processes, like using heat-resistant glass or linoleum or cork, and use them in a domestic context,” Kinchin said.

Philip Johnson, the founding director of MoMA’s Architecture Department, went as a student from Harvard to the Stuttgart exhibition.

“He was really bowled over, particularly by the work of Lilly Reich and Mies van der Rohe,” Kinchin said.

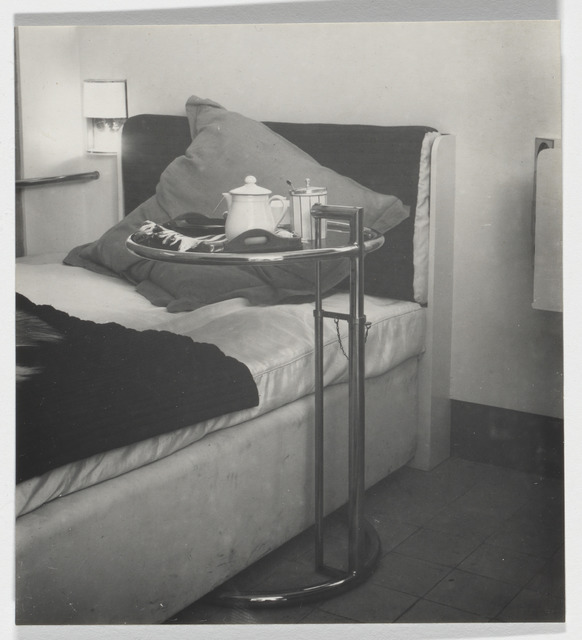

Johnson had an apartment in New York and, inspired by what he’d seen in Germany, later used the apartment as a kind of design lab, commissioning Reich and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe to design the interior. The bedroom, recreated in the museum, is austere. It features a single, tubular-steel framed bed and a dark blue, floor-to-ceiling silk curtain that matches the bedspread.

“It’s this idea of exploding the traditional interior and introducing more light and air and transparency, and more open planning, and dissolving the traditional distinctions between inside and outside,” Kinchin explained.

The exhibit is divided into three chronological groupings: the late 1920s to early 1930s, the late ’30s to early ’40s, and the late ’40s into the ’50s. It includes over 200 objects, but the highlights are really the large-scale interiors.

In addition to the 1926-‘27 Frankfurt Kitchen and Johnson’s 1930 bedroom, other interiors include Reich and Mies’ 1927 “Velvet and Silk Cafe,” featuring dramatic ceiling-to-floor drapes and tubular-steel, cantilevered chairs (in which visitors can sit and enjoy freshly brewed coffee). The show also includes a 1959 study bedroom by Charlotte Perriand and Le Corbusier, a guest bedroom by Eileen Gray and Jean Badovici, and a mock-up and meandering video of the Charles and Ray Eames’ home.

Adjoining the exhibit is a small grouping of works on the floor above, including a large weaving by Bauhaus designer Benita Koch-Otte, on view for the first time, and a range of tubular-steel furniture by Marcel Breuer.