Under Hawaii’s starriest skies, a fight over sacred ground

MAUNA KEA — Little lives up here except whispering hopes and a little bug called Wekiu.

Three miles above the Pacific, you are above almost half the oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere and every step hurts. A few minutes in the sun will fry your skin. Brains and fingers go numb. At night, the stars are so close they seem tangled in your hair.

Two years ago, this mountaintop was the scene of a cosmic traffic jam: honking horns, vans and trucks full of astronomers, VIPs, journalists, businesspeople, politicians, protesters and police — all snarled at a roadblock just short of the summit.

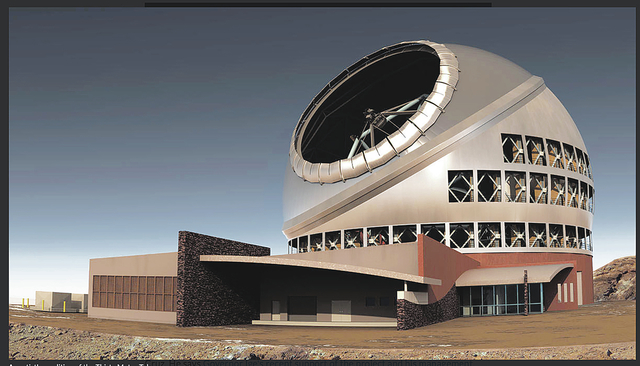

Abandoning their cars, some of the visitors started to hike up the hill toward what would have been a groundbreaking for the biggest and most expensive stargazing machinery ever built in the Northern Hemisphere: the Thirty Meter Telescope, 14 years and $1.4 billion in the making.

They were assembling on a plateau just below the summit, when Joshua Mangauil, better known by his Hawaiian name of Lanakila, then 27, barged onto the scene. Resplendent in a tapa cloth, beads, a red loin cloth, his jet black hair in a long Mohawk, he had hiked over the volcano’s cinder cones barefoot.

“Like snakes you are. Vile snakes,” he yelled. “We gave all of our aloha to you guys, and you slithered past us like snakes.”

“For what? For your greed to look into the sky? You guys can’t take care of this place.”

No ground was broken that day or since.

To astronomers, the Thirty Meter Telescope would be a next-generation tool to spy on planets around other stars or to peer into the cores of ancient galaxies, with an eye sharper and more powerful than the Hubble Space Telescope, another landmark in humanity’s quest to understand its origins.

But to its opponents, the telescope would be yet another eyesore despoiling an ancient sacred landscape, a gigantic 18-story colossus joining the 13 telescopes already on Mauna Kea.

Later this month, proponents and opponents of the giant telescope will face off in a hotel room in the nearby city of Hilo for the start of hearings that will lead to a decision on whether the telescope can be legally erected on the mountain.

Over the years, some have portrayed this fight as a struggle between superstition and science. Others view the telescope as another symbol of how Hawaiians have been unfairly treated since Congress annexed the islands — illegally in the eyes of many — in 1898. And still others believe it will bring technology and economic development to an impoverished island.

“This is a very simple case about land use,” Kealoha Pisciotta, a former telescope operator on Mauna Kea who has been one of the leaders of a group fighting telescope development on the mountain for the last decade. “It’s not science versus religion. We’re not the church. You’re not Galileo.”

Hanging in the balance is perhaps the best stargazing site on Earth. “Mauna Kea is the flagship of American and international astronomy,” said Doug Simons, the director of the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope on Mauna Kea. “We are on the precipice of losing this cornerstone of U.S. prestige.”

Big glass dreams

The road to the stars once ended in California at Palomar Mountain, whose 200-inch-diameter telescope was long considered the size limit. The bigger a telescope mirror is, the more light it can capture and the fainter and farther it can see — out in space, back in time.

In the 1990s, however, astronomers learned how to build telescopes with thin mirrors that relied on computer-adjusted supports to keep them from sagging or warping.

There was an explosion of telescope building that has culminated, for now, in plans for three giant billion-dollar telescopes: the European Extremely Large Telescope and the Giant Magellan, both in Chile, and the Thirty Meter Telescope.

Not only would they have a Brobdingnagian appetite for light, but they are designed to incorporate a new technology called adaptive optics, which can take the twinkle out of starlight by adjusting telescope mirrors to compensate for atmospheric turbulence.

Richard Ellis, a British astronomer now at the European Southern Observatory in Garching, Germany, recalled being optimistic in 1999 when he arrived at the California Institute of Technology to begin developing what became known as the Thirty Meter Telescope. “The stock market was booming,” he said. “Everything seemed possible.”

Canada, India and Japan eventually joined the project, now officially known as the TMT International Observatory. It has been helped along by The Betty and Gordon Moore Foundation, formed by the founder of Intel, which has contributed advice and $180 million.

The telescope, originally scheduled to be completed by 2024, is modeled on the revolutionary 10-meter-diameter Keck telescopes that Caltech and the University of California operate on Mauna Kea. Like them, it will have a segmented mirror composed of small, hexagonal pieces of glass fitted together into an expanse wider than a tennis court.

There are only a few places on Earth that are dark, dry and calm enough to be fit for a billion-dollar telescope.

Rising 33,000 feet from the seafloor, Mauna Kea is the second biggest mountain in the solar system — only Olympus Mons on Mars is greater. The dormant ancient volcano has been the center of Polynesian culture — the umbilical cord connecting Earth and sky — seemingly forever.

The mountain is part of so-called “ceded lands” that originally belonged to the Hawaiian Kingdom and are now administered by the state for the benefit of Hawaiians.

On its spare, merciless summit, craters and cinder cones of indefinable age keep company with a variety pack of architectural shapes housing telescopes.

In 1968 the University of Hawaii took out a 65-year lease on 11,000 acres for a dollar a year. Some 500 acres of that are designated as a science preserve. It includes the ice age quarry from which stone tools were being cut a thousand years ago, and hundreds of shrines and burial grounds.

The first telescope went up in 1970. Many rapidly followed.

Places like Mauna Kea are “cradles of knowledge,” said Natalie Batalha, one of the leaders of NASA’s Kepler planet-hunting mission. “I am filled with reverence and humility every time I get to be physically present at a mountaintop observatory.”

But some Hawaiians worried that knowledge was coming at too great a cost.

“All those telescopes got put up with no thought beyond reviving the Hilo economy,” said Michael Bolte, an astronomer from the University of California, Santa Cruz, who serves on the TMT board.

“Not a lot of thought was given to culture issues.”

Some native Hawaiians complained that their beloved mountain had grown “pimples,” and that the telescope development had interfered with cultural and religious practices that are protected by state law.

Construction trash sometimes rolled down the mountain, said Nelson Ho, a photographer and Sierra Club leader who complained to the university. “They wouldn’t listen,” he said. “They just kept playing king of the mountain.”

An audit by the state of Hawaii in 1998 scolded the university for failing to protect the mountain and its natural and cultural resources. An environmental impact study performed by NASA in 2007 similarly concluded that 30 years of astronomy had caused “significant, substantial and adverse” harm to Mauna Kea.

A step back for NASA

The tide began to shift in 2001 when NASA announced a plan to add six small telescopes called outriggers to the Keck complex. The outriggers would be used in concert with the big telescopes as interferometers to test ideas a for a future space mission dedicated to looking for planets around other stars.

Pisciotta led a band of environmentalists and cultural practitioners who went to court to stop NASA. The group included the Hawaiian chapter of the Sierra Club and the Royal Order of Kamehameha, devoted to restoring the Kingdom of Hawaii.

Pisciotta said she had once dreamed of being a cosmologist but lacked the requisite math skills and instead took a night job operating a radio telescope on Mauna Kea. She became disenchanted when a family shrine disappeared from the summit and the plans for the outriggers impinged on a cinder cone.

“Cinder cones are burial sites. It’s time to not let this go on,” she said. The group prepared for court by reading popular books about trials.

In 2007, Hawaii’s third district court found the management plan for the outriggers was flawed and revoked the building permit.

“NASA packed up and left,” Pisciotta said.

Encountering aloha

The prospective builders of the TMT knew they had their work cut out for them.

In 2007, the Moore Foundation hired Peter Adler, a consultant and sociologist, to look into the consequences of putting the telescope in Hawaii.

“Should TMT decide to pursue a Mauna Kea site,” his report warned, “it will inherit the anger, fear and great mistrust generated through previous telescope planning and siting failures and an accumulated disbelief that any additional projects, especially a physically imposing one like the TMT, can be done properly.”

The astronomers picked a telescope site that was less anthropologically sensitive, on a plateau below the summit with no monuments or other obvious structures on it. They agreed to pay $1 million a year, a fifth of which would go to the state’s Office of Hawaiian Affairs and the rest to stewardship of the mountain.

Quietly, they also pledged another $2 million a year toward science and technology education and workforce development on the island of Hawaii. The Moore Foundation also put some $2 million into the Imiloa Astronomy Center, a museum and planetarium run by the University of Hawaii.

Bolte, a mild-mannered UCSC professor with a soothing lilt to his voice, became one of the most visible promoters of the project in community meetings.

He recalled going to a meeting in Hilo once where tensions were very high. Afterward, he said, he was afraid to go out to his car.

Sure enough, a crowd rushed him when he got there. “What kind of astronomy do you do?” they asked eagerly.

“The aloha spirit really exists,” Bolte said.

“Exploring the universe is a wonderful thing humans do,” he added. Nevertheless, “there was a core we never won over.”

“In retrospect, we might have underestimated the strength of the sovereignty movement.”

The Hawaiian renaissance

In the years since the first telescopes went up on Mauna Kea, Hawaiian people and culture had experienced a resurgence of pride known as the Hawaiian Renaissance.

In 1976, a band of Hawaiians sailed the outrigger canoe Hokulea from Hawaii to Tahiti. The feat showed how ancient Polynesians could have purposefully explored and colonized the Pacific, navigating the seas using only the sun, stars, ocean swells and wind.

“And that was the first spark of shutting up everybody who said that we were inferior, that we were not intelligent,” said Mangauil, the protester.

In 1978, the state recognized Hawaiian, which once had been banned from schools, as an official language.

With rising pride came — at least among some more vocal native Hawaiians — questions about whether the occupation and annexation of Hawaii by the United States in the 1890s was legal.

Telescopes on a sacred mountain constitute a form of “colonial violence,” in the words of J. Kehaulani Kauanui, an anthropologist at Wesleyan University.

Or as Robert Kirshner, a Harvard professor who is now also chief science adviser to the Moore Foundation, put it, “The question in that case become not so much whether you did the environmental impact statement right, but whose island is it?”

Having cut their teeth fighting the outrigger project, Pisciotta’s group, known informally as the Mauna Kea Hui, was prepared when the TMT Corp. formally selected the mountain for its site in 2009.

Many Hawaiians welcomed the telescope project. At a permit hearing, Wallace Ishibashi Jr., whose family had an ancestral connection to Mauna Kea, compared the Thirty Meter’s mission to the search for aumakua, the ancestral origins of the universe.

“Hawaiians,” he said, “have always been a creative and adaptive people.”

Pisciotta and her friends argued among other things that an 18-story observatory, which would be the biggest structure on the whole island of Hawaii, did not fit in a conservation district.

In a series of hearings in 2010 and 2011, the state land board approved a permit for the telescope but then stipulated that no construction could begin untila so-called contested case hearing, in which interested parties could present their arguments, was held.

^

The Walk of Fame

The state won that hearing, and a groundbreaking ceremony was scheduled for Oct. 7, 2014.

The groundbreaking was never intended to be a public event, said Bob McClaren, associate director of the University of Hawaii’s Institute for Astronomy, which is responsible for scientific activities on the mountain.

“I thought it was reasonable to restrict access to those who were invited,” he said.

Mangauil, who makes his living teaching hula dancing and Hawaiian culture, said later that he had wanted only to make the astronomers feel uncomfortable to be on the mountain and to get protesters’ signs in view of the television cameras.

In an interview, he said he had nothing against science or astronomy, but did not want it on his mountain.

“Our connection to the mountain is like, that’s our elder, the mother of our resources,” he said. “We’re talking about the wau akua, the realm of where the gods live.”

There are no shrines on the very summit, he pointed out, which should be a lesson: Not even the most holy people are supposed to go there.

Unable to get to the groundbreaking, the Hawaiians formed their own blockade. Tempers flared.

“We were seeing the native Hawaiian movement flexing its muscles,” Bolte said.

Seeing people hiking up the mountain past the port-o-potties, Mangauil stormed after them and wound up on the hood of a ranger truck, even more angry.

Guarding the mountain

Lanakila’s barefoot run set the tone for two years of unrest and demonstrations.

Protesters calling themselves Guardians of the Mountain set up a permanent vigil across the road from the Mauna Kea visitor center, stopping telescope construction crews and equipment from going up. Dozens were arrested.

Gov. David Ige has tried to appease both sides. While saying that “we have in many ways failed the mountain,” he said the Thirty Meter Telescope should go forward, but at least three other telescopes would have to come down.

Astronomers and business leaders grew frustrated that the state was not doing enough to keep the road open for construction trucks and workers.

“The result of the faulty law enforcement surrounding Mauna Kea is fostering tension, aggression, racism and business uncertainty,” business organizations and the Hawaii Chamber of Commerce wrote to the governor. “Ambiguity surrounding the rule of law has prompted a poor economic climate.”

Stopping trucks on the steep slope was dangerous, said Bolte, adding that “people were basically trapped at the summit.”

Simons, the Canada-France-Hawaii director, grew increasingly worried about the effect of the protests on the astronomers, who became reluctant to be identified as observatory staffers.

“It really tugged at us to see the staff going from being proud to scared in a matter of weeks,” he said.

Meanwhile Pisciotta’s coalition was plugging through the courts.

On Dec. 2, the Hawaiian Supreme Court revoked the telescope building permit, ruling that the state had violated due process by handing out the permit before the contested case hearing.

“Quite simply, the Board put the cart before the horse when it issued the permit,” the court wrote.

Game of domes

By mid-December, Clarence Ching, another member of the opposition, stood in a crowd with other Hawaiians and watched trucks carrying equipment retreat from the mountain.

“David had beaten Goliath,” he said. “We were even happy and sad at the same time — sad, for instance, that somebody had to lose — as we had fought hard and long.”

The court’s decision set the stage for a new round of hearings, now scheduled to start in mid-October. The case, presided over by Riki May Amano, a retired judge appointed by the Land Board, is likely to last longer than the first round, which consumed seven days of hearings over a few weeks, partly because there are more parties this time around.

Among them is the pro-telescope Hawaiian group called Perpetuating Unique Educational Opportunities or PUEO, who contend the benefits of the TMT to the community have been undersold.

Whoever wins this fall’s contested case hearing, the decision is sure to be quickly appealed to the Hawaiian Supreme Court.

In an interview, Edward Stone, a Caltech professor and vice president of the Thirty Meter Telescope International Observatory, the group that will build the telescope, set April 2018 as the deadline for beginning construction. Depending on how it goes in Hawaii or elsewhere, the telescope could be ready sometime in the last half of the next decade.

“We need to start building this thing somewhere,” he said.

“We still hope Hawaii will work,” he added. “What we need is a timely permit, and we need access to the mountain once we have a permit.”

But there is no guarantee that even if the astronomers succeed in court they will prevail on the mountain. In an email exchange, J. Douglas Ing, lawyer for the MMT Observatory, said they were “cautiously optimistic” that local agencies would uphold the law, but the astronomers have also been investigating alternative sites in Mexico, Chile, India, China and the Canary Islands.

“It’s wise of the TMT to be exploring other sites,” said Richard Wurdeman, the lawyer for the Mauna Kea Hui.

I asked Pisciotta what would happen if the giant telescope finally wins.

“It would be really hard for Hawaiian people to swallow that,” she said. “It’s always been our way to lift our prayers up to heaven and hope they hear us.”

Bolte said he had learned to not make predictions about Hawaii.

In a recent email, he recalled photographing a bunch of short-eared Hawaiian owls. “These are called pueo, and they are said to be the physical form of ancestor spirits,” Bolte recounted.

Referring to the Hawaiian term for a wise elder, he said, “I had one kupuna tell me it was a great sign for TMT that so many pueo sought me out that trip, and another tell me it was a sign that we should leave the island immediately before a calamity falls on TMT.”

© 2016 The New York Times Company