WAIKOLOA — Nearly two centuries ago, Paul Dahlquist’s great-great-grandfather explored the remote, rugged steppe that is Kazakhstan.

Thomas Atkinson and his wife were helped in this years-long, saddle-sore undertaking by Czar Nicholas I, who gave the couple a pass that entitled the adventurers to every convenience available.

Hundreds of years later, that traversed county is inviting the family of the famous explorer back to where the story began.

Later this month, the government of Kazakhstan will host Waikoloa’s Dahlquist ohana, who will retrace the steps of their ancestors. They’ll visit a sacred spring site where a great-grandfather was born, visit culturally significant places and museums and ponder the impressions the land must have made on their ancestors long ago.

Only this time, they’ll be arriving by jet in a thriving new capital that has sprung up since the country’s independence from Russia 25 years ago. They will visit with the prime minister, rub elbows at embassies, take part in the filming of a documentary celebrating Kazakhstan’s independence.

And possibly sample horse meat and fermented mare’s milk — more on that later.

The family will have 10 days for a very packed itinerary.

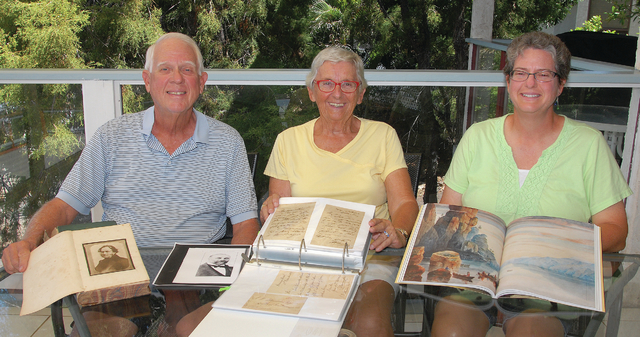

For Paul Dahlquist, a cultural anthropologist and former director of the Lyman Museum in Hilo where his wife Charlene also worked as an archivist — this trip could hardly be more appropriate, or exciting.

“It is living history,” he said at the couple’s home in Waikoloa Village. “To follow in the footsteps of a great explorer I never knew much about, whom my mother never talked much about.”

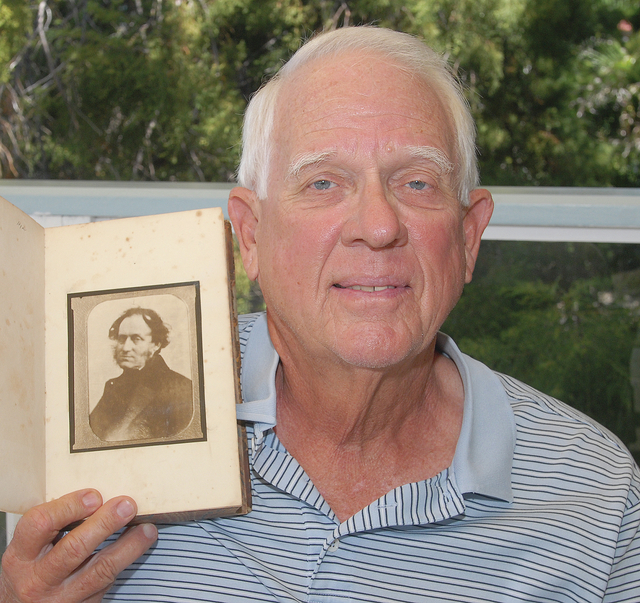

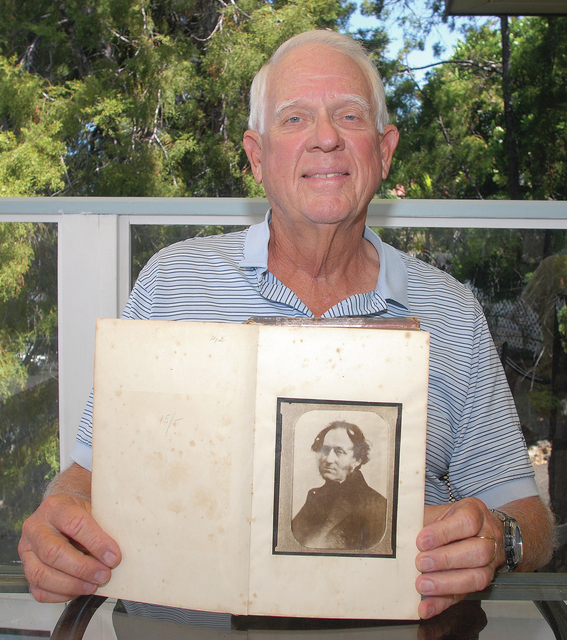

Today, the Dahlquists have binders containing hundreds of letter written by the explorer, including notes to Russian royalty and the famed author Charles Dickens. They have two moldering hardcover books he wrote and images of the more than 500 watercolors the man painted in this remote and breathtaking section of the globe.

The history sat for years in cardboard boxes, which were eventually passed on to them by Paul Dahlquist’s mother.

The Dahlquists aren’t sure why the great explorer wasn’t spoken of more in their family, but they have a clue.

It seems Atkinson, while being lauded by English high society for his exploration, painting and written accounts, had a little secret. He was married to two women at the same time, one who had remained in the west and would lay claim to his estate after his death, and one who accompanied him on the exploration and gave birth to his son at the Tamchiboulac spring in the Alatau mountains.

Ah, the twists of history.

“It’s really exciting to find out all of this, to go where they were traveling by horseback, on sleds, and camels,” Dahlquist said.

That son, who was born by the sacred spring, Alatau Tamchiboulac Atkinson, emigrated to Hawaii in 1869, taking charge of St. Alban’s College, which later became Iolani School. His daughter Molly married Samuel Wilder II, son of the Hawaii shipping and transportation magnate.

Sam and Molly were Paul’s grandparents.

Researchers from Britain have spent at least the last two decades piecing together the history of Thomas Atkinson’s days of exploration.

They’ve sifted through the Dahlquist’s letters, but Charlene doubted at the time that much would come of it. These descendants of Atkinson didn’t really catch the eye of the Khazakhstan government until the publication of the book “South to the Great Steppe: The Travels of Thomas and Lucy Atkinson in Eastern Kazakhstan,” written by journalist Nick Fields and published in 2015.

The Dahlquists are part of a group of 10 descendants on the government’s invite list.

For Charlene, it will be exciting to see a context develop for the letters she painstakingly transcribed into typewritten form, for the watercolor paintings, and for the steep Alatau mountains and spring whose name is born by the dark, sober eyes of an ancestor staring back at her from the old photographs.

In all, the Dahlquists know little about where they are headed — which is a theme for explorers.

Paul Dahlquist postulates that the whisperings of his ancestors’ genes are behind his own interest in anthropology and the study of peoples throughout the world.

Kristine Dahlquist, Paul’s daughter, teaches math at Hawaii Preparatory Academy. Saturday, she peered at a guidebook and pursed her lips over words like tenge — the currency of Kazakhstan. She found that the country, sandwiched between Russian and Uzbekistan, has 16 million people. It is the world’s largest landlocked country.

She has heard about the culture’s fondness for horse meat and fermented mare’s milk.

“I’m a vegan,” she confessed. “I haven’t eaten red meat in 20 years. It’s going to be a little hard for me to eat in Kazakhstan. But I’m going to be bringing my granola bars. It’s OK, I can handle it.”