Exhibit unfolds origami’s beauty as large-scale art

LOS ANGELES — Remember those origami cranes you meticulously folded out of tiny slips of paper in elementary school? Imagine them 100 times larger, as a massive swan made out of corrugated board, its swooping wings stretching the length of a room.

That piece, “Ruga Swan” by Chinese artist and designer Jiangmei Wu, is one of many large-scale origami artworks in the exhibit “Above the Fold: New Expressions in Origami,” at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles until Aug. 21. The show opened in January 2015 in Springfield, Massachusetts, and will have been in nine cities by the time it closes in 2020 in Wausau, Wisconsin.

Featuring nine international contemporary artists, the exhibit explores origami, the 1,000-year-old Japanese tradition of folding paper into objects, as much more than small-scale craft.

“Everyone has seen the cranes. A lot of people are not aware of what can be done with folded paper in the art world,” said the exhibit’s curator Meher McArthur. “These pieces are very complex and abstract. It’s not what you typically consider origami. They’re much more sculptural.”

American origami master Robert Lang’s “Vertical Pond II” showcases groups of colorful koi fish — sculpted out of 60 uncut sheets of paper — lining a wall. Nearby, his “Pentasia” is made with 500 squares of yellow and gray paper folded, interlocked and stacked like a miniature city.

Japanese artist Yuko Nishimura’s 3-D, wall-mounted pieces include a complicated display of pleated white circles within circles called “Shine.”

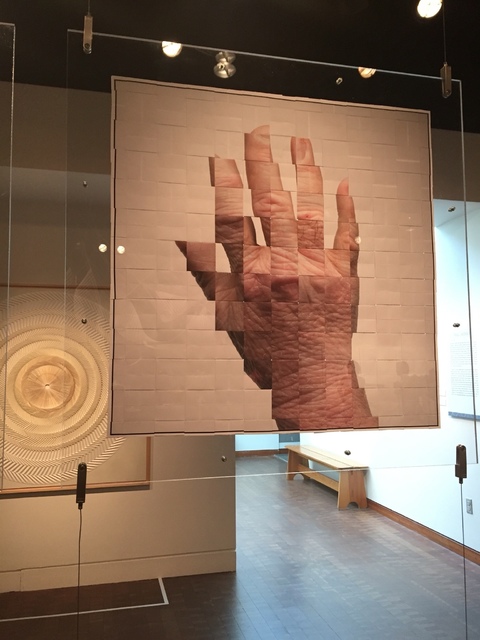

Based in Israel with his Israeli artist wife Miri Golan, who has three works in the exhibit, British artist Paul Jackson called his untitled piece a reflection on how “notions of front, back, left, right become one during the process of folding.” Hanging from the ceiling, the installation features four panels, two of them showing photo images of the front of his hands, and two showing the back of his hands. Jackson combined digital prints and a folding technique to create the two-sided images.

“Origami is a kind of alchemy, transforming ‘garbage’ — paper — into objects that are beautiful, clever and cool,” mused Jackson. “It is something anyone can do anywhere at any time, regardless of age, gender, faith or background.”

While McArthur noted that YouTube videos are good resources for origami beginners, Jackson and Golan suggested learning the art from books. They also recommended the website OrigamiUSA.com for local and global classes, groups and conventions.

Newbies can start with straightforward designs such as cranes, boxes and boats using a simple square piece of paper.

Golan, like Jackson, discovered origami as a kid. She later founded the Israeli Origami Center, which trains and places origami teachers in Jewish, Muslim and Christian schools, and Folding Together, an organization showcasing origami as a way to unite Israeli and Palestinian children. She also developed the program Origametria, which uses origami to teach geometry in schools.

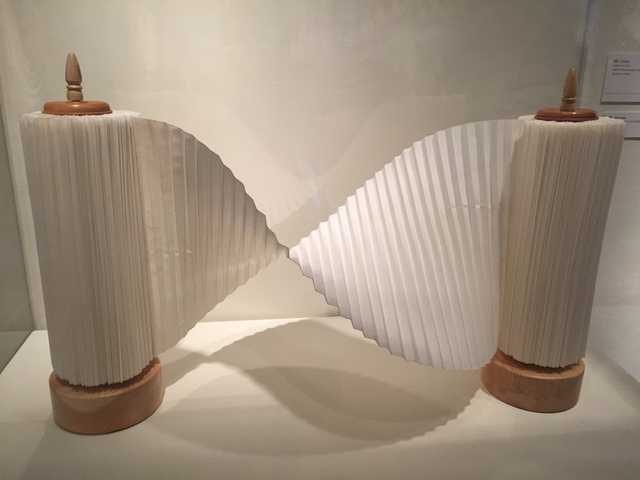

Each of her pieces in the exhibit, including two scrolls connected by a twisted, pleated, white sheet of paper and resembling both the Jewish Torah and Muslim Quran, took roughly four to six days to complete.

“The exhibition gives me a chance to bring together my professional and personal sides in a series of works that express my frustrations with the situation here in the Middle East,” Golan said.

Canadian father-son artistic partners Martin Demaine, 73, and Erik Demaine, 35, both based at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, work in a field known as “computational origami.” It’s a branch of computer science that studies math algorithms for solving paper-folding problems.

The pair’s sleek, looping, curving “Destructors” and “Together” sculptures are made of circles of paper that bend according to natural creases and are interwoven through holes in the center of each circle, explained Martin Demaine.

“Our work grows directly out of our decades collaborating together in mathematics and sculpture,” said Erik Demaine, who joined MIT’s faculty at age 20.

Paper is also, of course, vulnerable. Installing, packing and shipping large-scale origami is challenging (issues include humidity).

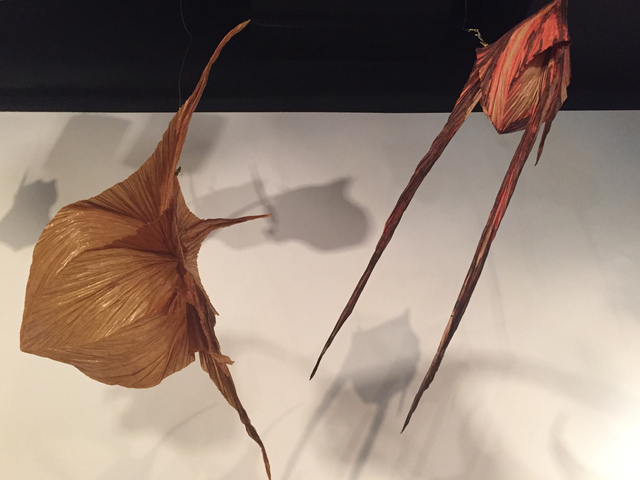

French artist Vincent Floderer takes on the idea of fragility, said McArthur. Made of crumpled and inflated tissue paper, the sea urchin-like creatures of Floderer’s “Unidentified Flying Origami” dangle from the ceiling.

“These pieces were not made to last,” said McArthur. “They’re actually made to decompose and be like nature, to be born and then die.”