RALEIGH, N.C. — It was, without a doubt, the nicest rejection of my journalistic career. ADVERTISING RALEIGH, N.C. — It was, without a doubt, the nicest rejection of my journalistic career. I was working on a project about whether “Southernness”

RALEIGH, N.C. — It was, without a doubt, the nicest rejection of my journalistic career.

I was working on a project about whether “Southernness” was an outdated notion in our mobile culture, and was looking for regional icons to share their thoughts. One of the first names that popped into my mind was Harper Lee.

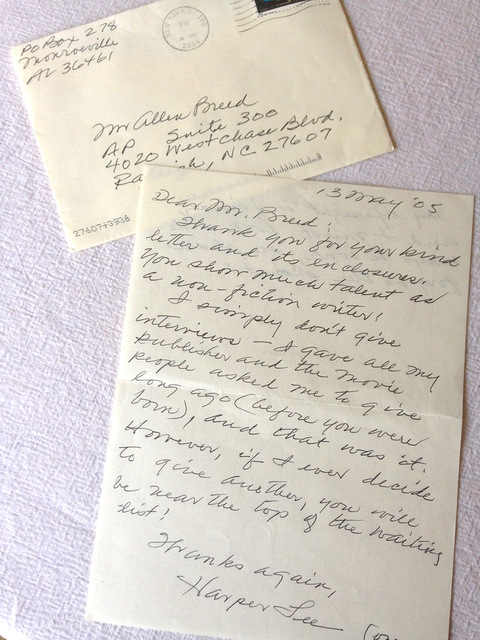

The author of “To Kill a Mockingbird” hadn’t granted an interview in about four decades, but I figured it was worth a shot. So I crafted a letter and sent it off to Monroeville, Alabama, care of attorney Alice F. Lee — the author’s older sister and chief gatekeeper.

“I know you have had any number of journalistic suitors over the years,” I began, “but I hope you won’t mind one more.”

I told Lee about my project, and that she — as someone who’d divided her time between New York City and Monroeville — would be a perfect fit. I even included some of my favorite feature stories — as proof of my bona fides, I suppose.

It was the height of wishful thinking. I didn’t really expect a reply.

Nine days later, a letter arrived. It was postmarked in New York, but the return address was a post office box in Monroeville.

The note was brief.

“Dear Mr. Breed:

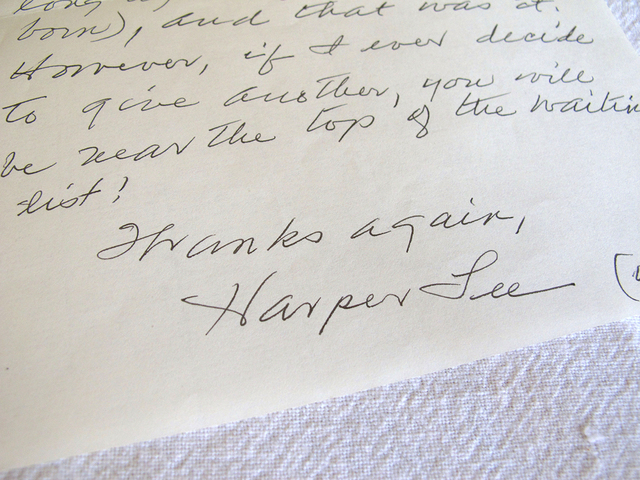

“Thank you for your kind letter and its enclosures. You show much talent as a non-fiction writer!” she wrote in a clear script that sloped somewhat down to the right.

“I simply don’t give interviews — I gave all my publisher and the movie people asked me to give long ago (before you were born), and that was it. However, if I ever decide to give another, you will be near the top of the waiting list!”

There was a brief postscript on the backside of the page.

“My eyesight is failing, and I must look sideways to write,” it read, “so please forgive the slant!”

Wow!

Like so many, I was in junior high school when an English teacher introduced me to Southern lawyer Atticus Finch and his two children, Jem and Scout. We were assigned “Mockingbird,” William Golding’s “Lord of the Flies” and S.E. Hinton’s “The Outsiders” all in the same year — a magical year which taught me that reading needn’t be a chore.

Growing up in a relatively integrated former mill town north of Boston, the fictional Maycomb, Alabama, was my first real exposure to the evils of segregation. The tale of Atticus’ quixotic defense of Tom Robinson — the disabled black handyman who finds himself charged with rape for having the audacity to feel sorry for a poor, abused white girl — left a lasting impression on me.