Ex-SS guard on trial in late push to punish Nazi crimes

DETMOLD, Germany — A 94-year-old former SS guard at the Auschwitz death camp is going on trial this week on 170,000 counts of accessory to murder, the first of up to four cases being brought to court this year in an 11th-hour push by German prosecutors to punish Nazi war crimes.

Reinhold Hanning is accused of serving as an SS Unterscharfuehrer — similar to a sergeant — in Auschwitz from January 1943 to June 1944, a time when hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews were brought to the camp in cattle cars and were gassed to death.

The trial for the retiree from a town near the western city of Detmold starts on Thursday and is one of the latest that follow a precedent set in 2011, when former Ohio autoworker John Demjanjuk became the first person to be convicted in Germany solely for serving as a camp guard, with no evidence of involvement in a specific killing.

The verdict vastly widened the number of possible prosecutions, establishing that simply helping the camp to function was sufficient to make one an accessory to the murders committed there. Before that, prosecutors needed to present evidence of a specific crime — a difficult task with few surviving witnesses and perpetrators whose names were rarely known and whose faces were often only seen briefly.

Hanning’s attorney, Johannes Salmen, says that his client acknowledges serving at the Auschwitz I part of the camp complex in Nazi-occupied Poland, but denies serving at the Auschwitz II-Birkenau section, where most of the 1.1 million victims were killed.

Prosecutor Andreas Brendel told The Associated Press, however, that guards in the main camp were also used as on-call guards to augment those in Birkenau when trainloads of Jews were brought in.

“We believe that these auxiliaries were used in particular during the so-called Hungarian action in support of Birkenau,” he said.

Leon Schwarzbaum, a 94-year-old Auschwitz survivor from Berlin who is the first witness scheduled for the trial, said he can’t forget the vivid images he witnessed there.

“The chimneys were spewing fire … and the smell of burning human flesh was so unbelievable that one could hardly bear it,” he told reporters Wednesday.

Though he said he felt deeply unsettled about staring Hanning in the eyes in the courtroom Thursday, he said he thought it was important to be there and that more than punishment, he hoped the trial would give the former SS man an opportunity to give a full accounting of what he saw and did.

“It’s perhaps the last time for him to tell the truth. He has to speak the truth,” Schwarzbaum said.

In all, about 40 Auschwitz survivors or their relatives have joined the trial as co-plaintiffs, as allowed under German law, though not all will testify.

Hanning’s case is one of some 30 involving former Auschwitz guards investigated by federal prosecutors from Germany’s special Nazi war crimes office in Ludwigsburg. It was sent to state prosecutors in 2013 with the recommendation that they pursue charges after the office undertook a major review of its files following the Demjanjuk verdict.

Although Demjanjuk always denied serving at the death camp and died before his appeal could be heard, prosecutors last year managed to use the same legal reasoning to successfully convict SS Unterscharfuehrer Oskar Groening, who served in Auschwitz, on 300,000 counts of accessory to murder.

Groening’s appeal is expected to be heard sometime this year, but prosecutors are not waiting to move ahead with other cases.

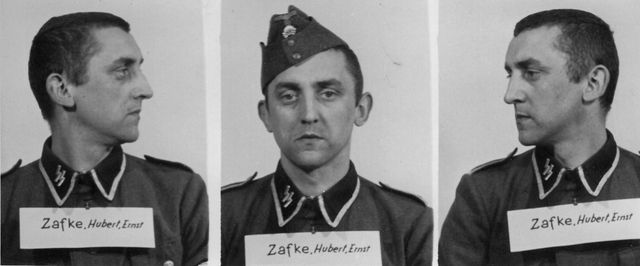

Hubert Zafke, 95, a former SS Oberscharfuehrer — roughly equivalent to a Sgt. 1st Class — is scheduled to go on trial at the end of February in Neubrandenburg, north of Berlin, on 3,681 counts of accessory to murder on accusations he served as a medic at an SS hospital in Auschwitz in 1944.

His attorney, Peter-Michael Diestel, says it is Germany’s “shame” that many higher-ranking Auschwitz perpetrators and other Nazi war criminals were able to escape with minimal or no sentences in the initial years after the war, and questions whether prosecutors are trying “to make up for mistakes of the past” with his client.

“He was a medic for Wehrmacht (army) soldiers and SS men — for uniformed men — and had no part of the Holocaust, but the judicial argument of the Demjanjuk verdict says that if he didn’t provide his service as a medic then Auschwitz wouldn’t have functioned,” Diestel said. “What should a young man, even if he knew what was going on in Auschwitz, do to stop it?”

There is no question there were “some serious failures by the German judicial system in the past,” says Efraim Zuroff, the head Nazi-hunter at the Simon Wiesenthal Center. But “that doesn’t in any way change the validity of what’s happening now.”

Two others whose cases are likely to go to trial this year are a 93-year-old woman charged with 260,000 counts of accessory to murder on allegations she served as a radio operator for Auschwitz’s commandant in 1944, and a 94-year-old man charged with 1,276 counts on allegations he served as an Auschwitz guard.