As part of Volcano Awareness Month, our January “Volcano Watch” articles are taking us on a geologic tour of the Hawaiian Islands. Today’s stop: Maui, as well as the islands of Lanai, Molokai, and Kahoolawe, all of which form Maui County.

As part of Volcano Awareness Month, our January “Volcano Watch” articles are taking us on a geologic tour of the Hawaiian Islands. Today’s stop: Maui, as well as the islands of Lanai, Molokai, and Kahoolawe, all of which form Maui County.

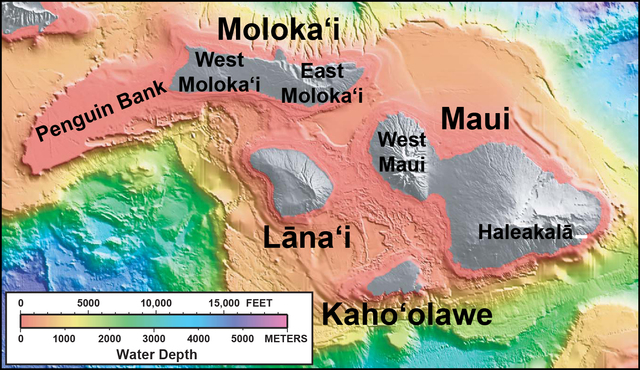

To imagine the landscape of Maui County as it would have appeared about one million years ago, think of the Island of Hawaii today, with several large, coalesced volcanoes that form a single large island. Such was the heyday of “Maui Nui,” when at least seven volcanoes built an island that was about 50 percent bigger than the Island of Hawaii is today.

The oldest of Maui Nui’s volcanoes, Penguin Bank, is now submerged off the west coast of Molokai. From there, successively younger volcanoes are West Molokai and East Molokai. When these three volcanoes began to grow on the seafloor is poorly known, but they probably range from slightly over two million years old (Penguin Bank) to slightly less than two million years old (East Molokai).

The sequence of volcanoes then progressed with Lanai, West Maui, Kahoolawe, and finally, Haleakala on East Maui. The formation of these four volcanoes probably occurred between 1.5 and two million years ago.

Why so many volcanoes in such a small area? Studies of the entire chain of Hawaiian volcanoes and seamounts suggest that magma supply to the surface began increasing a few million years ago. More magma means more eruptions, which might explain why the Hawaiian hot spot went from forming individual island volcanoes (Niihau and Kauai, to an island with two volcanoes (Oahu), to islands made up of several volcanoes (Maui Nui and the Island of Hawaii).

Despite their close proximity, the volcanoes of Maui Nui have quite different eruptive histories. For example, Lanai was short-lived, going extinct after its vigorous shield stage, with no eruptions since about 1.35 million years ago. West Molokai and Kahoolawe were also short-lived, but they experienced minor postshield volcanism before going extinct about one million years ago. East Molokai and West Maui persisted longer and were the sites of rejuvenated eruptions just 300,000 years ago (the most recent such eruption on Molokai formed Kalaupapa Peninsula).

Haleakala, the longest-lived of the Maui Nui volcanoes, is currently waning from a long postshield sequence of volcanism. Eruptions there occur about as frequently as they do on Hualālai volcano on the Island of Hawaii. The most recent eruption on Haleakala took place about 400 years ago, well within the time that Polynesians settled on the Hawaiian Islands. Future eruptions at Haleakala are likely, which is why the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) maintains a monitoring network there.

Because all of the Maui Nui volcanoes are beyond their vigorous shield-building stages, erosion has dominated for the past one million years or so. Water and landslides have helped create dramatic valleys, including the summit “crater” of Haleakala.

The most spectacular of the Maui Nui landslides occurred from East Molokai, where the massive Wailau slide sliced off the volcano’s summit, creating spectacular sea cliffs on the island’s north side. This landslide deposited rocky debris over 100 miles across the ocean floor.

The islands of Maui Nui have also subsided over time — a normal consequence of the volcanoes’ weight on the sea floor in addition to their motion away from the buoyant hot spot. It was this subsidence, plus rising sea levels, that flooded the land between Maui Nui’s volcanoes, creating the separate islands we see today, probably within the last few hundred thousand years. With continued subsidence at present rates, Haleakala (East Maui) itself could become isolated from West Maui by a seaway within another 10,000 to 20,000 years.

As Volcano Awareness Month winds down next week, we’ll make the final stop in our geologic tour of the islands on the Island of Hawaii.

Before then, HVO scientists are offering Volcano Awareness Month talks in the Konawaena High School cafeteria on Monday; Hawaii Volcanoes National Park on Tuesday, Ocean View Community Center on Wednesday, and University of Hawaii at Hilo on Thursday. Details are posted on HVO’s website (https://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/) or you can email askHVO@usg.gov or call 967-8844 for more information.

Volcano activity updates

Kilauea continues to erupt at its summit and East Rift Zone. During the past week, the summit lava lake level varied between about 110 to 140 feet below the vent rim within Halemaumau Crater. On the East Rift Zone, scattered lava flow activity remained within about 4 miles of Puu Oo, and is not currently threatening nearby communities.

Mauna Loa is not erupting. Seismicity remains elevated above long term background levels. GPS measurements continue to show deformation related to inflation of magma reservoirs beneath the summit and upper Southwest Rift Zone of Mauna Loa.

One earthquake was reported felt on the Island of Hawaii during the past week. On Jan. 18, at 1:52 a.m., a magnitude-3.9 earthquake occurred 4.1 miles north of the Mauna Loa summit at a depth of 7.5 miles.

Visit the HVO website (https://hvo.wr.usgs.gov) for past Volcano Watch articles, Kilauea daily eruption updates, Mauna Loa weekly updates, volcano photos, recent earthquakes info, and more; call for summary updates at 967-8862 (Kilauea) or 967-8866 (Mauna Loa); email questions to askHVO@usgs.gov.