WASHINGTON — A shake-up of the nation’s kidney transplant system means more organs are getting to patients once thought nearly impossible to match, according to early tracking of the new rules. ADVERTISING WASHINGTON — A shake-up of the nation’s kidney

WASHINGTON — A shake-up of the nation’s kidney transplant system means more organs are getting to patients once thought nearly impossible to match, according to early tracking of the new rules.

It’s been a year since the United Network for Organ Sharing changed rules for the transplant waiting list, aiming to decrease disparities and squeeze the most benefit from a scarce resource: kidneys from deceased donors. Now data from UNOS shows that the changes are helping certain patients, including giving those expected to live the longest a better shot at the fittest kidneys.

The hope is to “really level the playing field,” said Dr. Mark Aeder, a transplant surgeon at University Hospitals Case Medical Center in Cleveland who is chairman of the UNOS’ kidney committee.

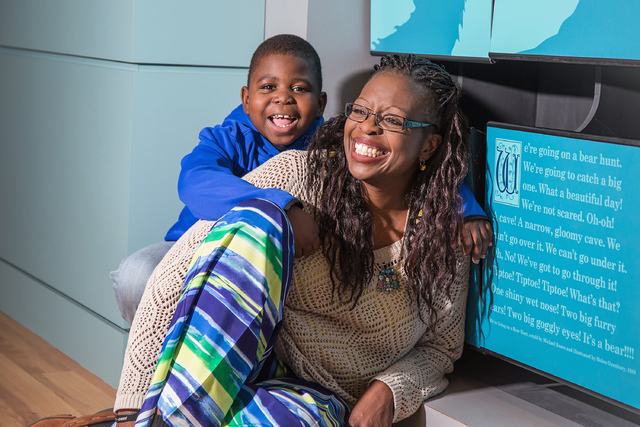

In Abingdon, Virginia, 8-year-old Marshall Jones was one of the lucky first recipients. A birth defect severely damaged his kidneys and a failed transplant when he was younger left his immune system abnormally primed to reject kidneys from 99 percent of donors.

Then last January, after four years of searching, organ officials found a possible match, hours away by plane but available under the new policy — and it worked.

“We don’t use the word lightly, but this was really a miracle kidney for him,” said Dr. Victoria Norwood, Marshall’s doctor and the pediatric nephrology chief at the University of Virginia.

There’s a huge gap between who needs a new kidney and who gets one. More than 101,000 people are on the national waiting list, while only about 17,000 kidney transplants are performed each year. Roughly 11,000 of them are with kidneys donated from someone who just died; the rest occur when a patient is able to find a living donor.

The wait for a deceased-donor kidney varies widely around the country, and in 2014, more than 4,500 people died before their turn.

The new kidney allocation system can’t alleviate the overall organ shortage. “The only thing to shorten total wait time for everybody is more organ donors,” Aeder said.

Instead, the policy altered how deceased-donor kidneys are distributed, shifting priorities so that how long you’ve been on the waiting list isn’t the main factor. Among the changes:

—fewer transplants are occurring in which the kidney is predicted to outlive the recipient. Now, the kidneys expected to last the longest — as calculated by donor age and medical history — are offered first to the patients expected to survive the longest. That’s called longevity matching. Before the change, 14 percent of the longest-lasting kidneys went to recipients age 65 or older. That dropped to 5 percent as the new policy kicked in, according to UNOS monitoring.

—the less time spent on dialysis, the better patients fare after a transplant. Yet where you live still plays a big role in how quickly you’re put on the transplant list, with minorities and those in rural and poorer areas spending more time on dialysis first. The new policy gives people credit for that dialysis time, moving them up the waiting list, and boosted transplants among long-time dialysis users, UNOS found. In turn, transplants inched up among African-Americans, who spend disproportionately more time on dialysis.

—then there are those hardest-to-match patients such as Marshall, about 8,000 of them now on the waiting list. The new policy gives them special priority for organs that can be shipped to a wider area of the country than other kidneys, broadening the search for a super-rare match.

As a result, the percentage of transplants among those patients has risen nearly fivefold, UNOS senior research scientist Darren Stewart said.

UNOS is tracking the changes closely to look for unintended problems because more transplants for one group can mean fewer for another. For example, adults younger than age 50 are getting more kidneys since the rule change, but older patients still account for about half of transplants.

Another question is how the new policy will work long term as a backlog of the special-case patients starts to clear.

“All of a sudden you got a floodgate that opens because you gave these people a big advantage and you’re shipping kidneys across the country to them,” said Dr. John Roberts, transplant chief at the University of California, San Francisco, one of the largest kidney programs. He praised the rule change but said it may need some fine-tuning.

For example, the new policy also offers wider access to the kidneys expected to last the shortest amount of time, because the oldest or sickest patients might choose one for a quicker transplant rather than gambling that a fitter one will become available. But, “we don’t have a great way to predict what’s coming for a patient” to help them decide, Roberts said. Discards of those less-fit kidneys temporarily increased a bit as the new policy began.

Stay tuned. Transplant centers are learning to handle the logistical hurdles of shipping more kidneys around the country, potentially opening additional avenues to alleviate geographic disparities, Aeder said. “There’s much more to come.”