TOLEDO, Ohio — Dozens of shipwrecks scattered along America’s coasts are thought to be holding oil and certainly will start leaking someday as corrosion eats away at their tanks. ADVERTISING TOLEDO, Ohio — Dozens of shipwrecks scattered along America’s coasts

TOLEDO, Ohio — Dozens of shipwrecks scattered along America’s coasts are thought to be holding oil and certainly will start leaking someday as corrosion eats away at their tanks.

Preventing that just isn’t possible, experts say, because funding for such a huge effort doesn’t exist and there are too many unknowns about the locations of those wrecks and the cargo left inside. Some are simply too deep to reach.

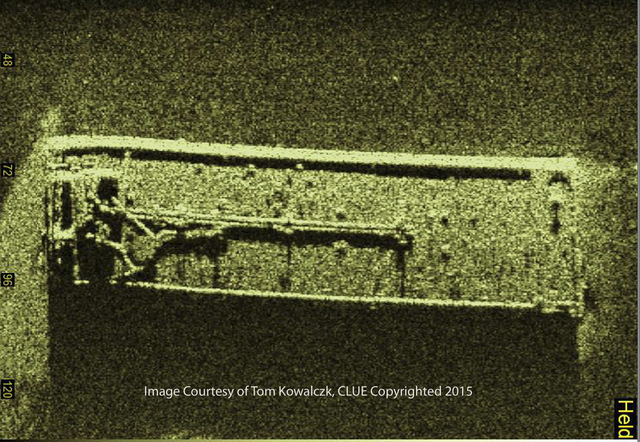

A sunken tanker barge recently discovered in Lake Erie that appears to be occasionally seeping an oil-based substance near the Canadian border is believed to be one of 87 shipwrecks on a federal registry that identifies the most serious pollution threats to U.S. waters.

Most of those wrecks are along the Atlantic seaboard, torpedoed by German submarines during World War II.

Other sunken ships thought to be holding oil are scattered along the Pacific Coast and in the Gulf of Mexico just off the Florida and Louisiana shorelines. Five are in the Great Lakes, including the Edmund Fitzgerald, which sank in 1975 and was memorialized in a song by Gordon Lightfoot.

Three out of every four wrecks on the list have been underwater at least seven decades, leaving them slowly rusting away. How fast isn’t known because research on corrosion rates is limited and each wreck is affected by varying depths, storms, currents and marine bacteria.

Past leaks have shown that the oil usually comes out in drips and drabs rather than gushes, lessening the worry of a full-scale catastrophe and the need for urgent action in most cases.

“Our coastlines are not littered with ‘ticking time bombs’ of oil,” said the risk assessment report released by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in 2013. “Although there are definitely vessels of concern in our waters that should be assessed and monitored.”

While some of the wrecked vessels are monitored by the U.S. Coast Guard and visited by recreational divers, many remain a mystery.

Only about half the wrecks have been located and identified. And little is known about their current condition or how much oil they may still be holding. The only clues come from historical records and witness accounts from when the vessels went down.

“That’s always one of the big challenges when we look at these wrecks,” said Lisa Symons of NOAA, who wrote the study. “Some of these are wicked deep, and not in an area where you could do survey work.”

The biggest obstacle, though, is money.

The cost of removing oil and other fuels from wrecks found over the past two decades has ranged from a couple of million dollars to tens of millions.

The money comes from the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund, which is overseen by the Coast Guard. It allows for $50 million to be spent annually on emergency spills and damage assessments, with any unspent amounts carried over. Last year, $62.4 million was spent from the emergency fund.

The money available isn’t nearly enough to remove all of the oil from wrecked vessels in U.S. waters. “It would be gone in a minute,” said Jacqueline Michel, a geochemist who has done extensive research on sunken oils and assisted with spill responses.

It’s not just a problem along America’s shores. The threat that shipwrecks pose in European waters, including the Mediterranean, Baltic and North seas, was the focus of a conference in early October in Gothenburg, Sweden.

“They have the same problem,” Michel said. “There’s no money until she starts leaking.”