The conversation atop Mauna Kea appears to have shifted, at least for now, away from the stalled Thirty Meter Telescope project and toward issues of jurisdiction and Hawaiian sovereignty. ADVERTISING The conversation atop Mauna Kea appears to have shifted, at

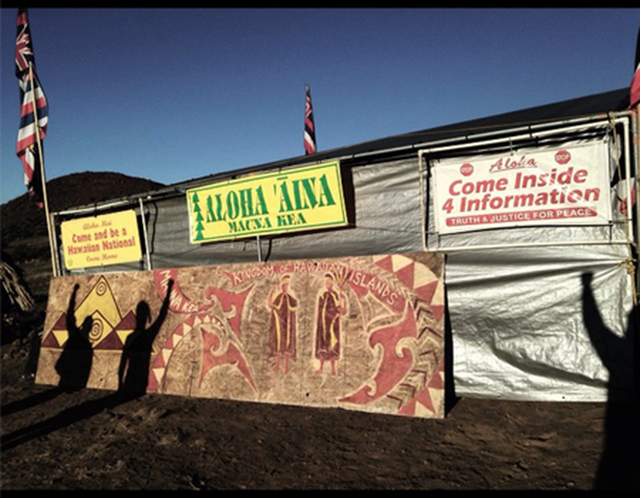

The conversation atop Mauna Kea appears to have shifted, at least for now, away from the stalled Thirty Meter Telescope project and toward issues of jurisdiction and Hawaiian sovereignty.

“The stand is still to protect the mountain, but now we have the (Lawful Hawaiian Government) standing with us,” said Lakea Trask, a leader in the months-long protest to stop the telescope from being built atop Hawaii’s tallest peak.

A group of Hawaiians founded the Lawful Hawaiian Government in 1999 to “reclaim their sovereign independent status,” according to the group’s website. The group does not recognize the state of Hawaii.

For the last week, officers with the state Department of Land and Natural Resources have made repeated visits to the recently relocated camp across from the Mauna Kea Visitor Information Station to distribute educational handouts and warn protesters that they are violating a new emergency rule limiting access on the mountain.

Meanwhile, protesters, many of whom are affiliated with the LHG sovereignty movement, argue the warnings and new rule are frivolous, and that the government behind them is unlawful.

Several lengthy, and sometimes awkward, encounters between protesters and state enforcement officials have been captured on camera and posted in daily updates on social media.

In a July 24 video, DLNR Officer John Holley can be seen telling a small group of protesters that forcing them off the mountain is not the approach the state wants to take, but that it will if laws continue to be broken.

“It’s just something that you have to all decide where you want to go with this,” Holley said. “The cause is noble, but on the same token, the law has to be upheld with the government that we have in place at this time, until such time another government takes over or the Kingdom (of Hawaii) is given back to you folks.

“In the meantime, the doctrine of necessity says we have to do our job for the people … all the people.”

Sam Keliihoomalu, a representative of the LHG, told Holley that the situation is “government-to-government,” and that it’s time top state officials contact LHG leaders to work things out. The emergency rule, he said, doesn’t apply to the Kingdom of Hawaii.

“It doesn’t apply to Hawaii nationals,” he said.

Holley said that while he would pass along the message, he couldn’t promise LHG would hear from state leaders.

The temporary rules, approved by the state Land Board earlier this month, are meant to deal with what state officials have described as an “imminent peril” to public safety and natural resources resulting from the protests. In addition to prohibiting certain camping gear, including tents, sleeping bags and stoves, the rule restricts being within a mile of Mauna Kea Access Road from 10 p.m. to 4 a.m. unless in a moving vehicle.

Still, two weeks after going into effect, no citations or arrests have been made.

“We get orders from above, and when that comes down to come cite, arrest, do whatever, then that’s what’s going to happen,” Holley tells Trask in a video posted July 22. “I can’t tell you when or where or how. We just get the orders and then we come.”

One problem, Trask told Holley, is that the new rule does not address religious rights.

“We’re here under a different set of laws, a different jurisdiction,” he said in the video. “And we’re here exercising our rights to this land.”

So far, the state has kept quiet about its plans to begin enforcement, other than to say it can occur at any time during the 120 days the rule is in effect.

“The state government — from the governor on down — is working to be diligent and deliberate about safety on Mauna Kea, and this includes making sure that people are aware of and understand the emergency rule,” Joshua Wisch, a spokesman for the Department of the Attorney General, wrote in an email. “This includes the posting of signs and the distribution of educational handouts.”

So far, it does not appear the state has any intention of acknowledging LHG.

“I don’t think they want to acknowledge LHG,” Trask said. “I think that would open up a whole new can of worms.”

Wisch did not respond Monday to questions about whether the state was in conversations with LHG.

While DLNR continues its effort to educate protesters about the emergency rule, protesters have provided DLNR with what they say are permits from the LHG allowing them to continue their round-the-clock “vigil” on the mountain.

Henry Noa, “prime minister” of LHG, said the emergency rule was created for the purpose of favoring development only.

“It was to give one side the upper hand,” he said.

Protesters also continue to raise concerns about the state’s decision to close the bathrooms at the visitor center, which they say has resulted in visitors defecating in nearby bushes. It is a health hazard that was created, and then ignored, by the state, they say.

Ultimately, Trask called the state’s response in recent weeks “sheer dysfunction.”

The nonprofit company building the Thirty Meter Telescope hasn’t indicated when there will be another attempt to resume construction. Workers weren’t able to reach the site during two previous attempts when they were blocked by hundreds of protesters, including dozens who were arrested.

University of Hawaii law school professor Williamson Chang has filed a petition with the DLNR seeking to repeal the rule, arguing it prevents telescope opponents from legally exercising their rights to peacefully protest.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Email Chris D’Angelo at cdangelo@hawaiitribune-herald.com.