The leadership at Kona Community Hospital heard from West Hawaii residents Monday night on why the state’s hospital safety net system shouldn’t balance its budget on the backs of Hawaii Island’s underserved population. ADVERTISING The leadership at Kona Community Hospital

The leadership at Kona Community Hospital heard from West Hawaii residents Monday night on why the state’s hospital safety net system shouldn’t balance its budget on the backs of Hawaii Island’s underserved population.

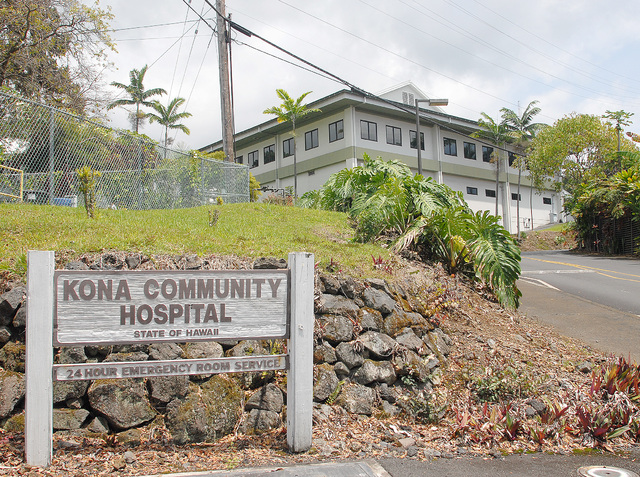

Repeatedly, residents said of the 94-bed Kealakekua facility: “This is all we have.”

The West Hawaii Region of the Hawaii Health Systems Corp. plans to cut 34 positions and close the skilled nursing unit at KHC to deal with a $6 million shortfall in the fiscal year starting July 1. That’s when employees will be notified of the cuts, and the reductions will be put in place over a 90-day period starting Aug. 1. The statewide system is in the red $50 million for the coming year.

Dianna Jones described the hardship of trying to find alternatives in West Hawaii while her husband spent 10 days in the Kona hospital’s skilled nursing unit in April, waiting for a similar bed to open elsewhere.

“Life Care was full,” she said. “There were no beds on the west side. It would have been an unsafe discharge.”

Close Kona’s skilled nursing unit and the hospital will have patients on its hands that it cannot discharge legally or safely, she predicted. They will stay in acute care beds and create a bottleneck in services there, Jones said.

Attendees were angry and baffled that the state could fail to fund something as basic as health care, and administrators and board members found little to disagree with in the fears raised by a room of about 80 people.

“If it’s true, and it very well could be, it’s going to be a problem,” CEO Jay Kreuzer told Jones. “Our issue right now is we have to pay our bills and pay our employees.”

The public hearing was part of the process for putting the cuts in place — an opportunity that residents and employees also took to cast doubts on the prospect of privatization of the state’s hospitals.

“My fear is that we are letting things happen to prove that’s where we need to go quickly,” said nurse Aviva Plaut. “When a private partner comes in, there is more necessity for profit. I don’t see how the math works.”

“We are definitely in a pickle,” Plaut said. “I’d like our representatives to be a bigger voice in the Legislature that these cuts are not an option.”

It is not an option for legislatures elsewhere to tell Kona it isn’t making enough revenue, Plaut contended.

“If the state can fund a $90 million judiciary building, it can fund medical care. I think we need to take care of our people,” said Ronald Hancock of Captain Cook.

The medical services people need “just aren’t there,” said Hancock, who suggested an emergency appropriation, a 1/2 percent sales tax dedicated to hospitals or taxing medical marijuana.

Administrators said they chose to close skilled nursing because they felt other facilities could offer those services, and they had to stay away from cutting the services that can’t be found elsewhere — like obstetrics, emergency care and pyschiatry.

Kreuzer said the shortfall is caused by increased labor costs from collective bargaining agreements and the hospital’s new requirement to pay retiree health benefits, which were previously covered by the state. The hospital would otherwise have broken even after a streamlining effort last year, which Kreuzer said identified $4.5 million in one-time savings and $4.5 million in recurring savings. The facility of 415 employees has $65 million in operating revenue for the coming fiscal year.

Long term, the hospital must either gain more funding from the Legislature or enter a public-private partnership, Kreuzer said.

“We’re going to be fighting this,” he said, noting that the hospital’s leadership is not sitting idle, and that residents should press the matter with their lawmakers.

The hospital’s regional board of directors chairman Bill Cliff told the group: “I want you to know we really agonized over this, and this is a case of us trying to find the least worse scenario.”

Kreuzer has said he hopes the closing of the skilled nursing unit will be temporary and last only until the hospital’s funding is better. The unit provides for patients who are no longer considered acute but still need therapy or other care before they can return home. The unit averages six patients on any given day, administrators say. But a hospital employee who claims to have worked there nearly three decades disputed the figure.

“The average is eight to 13 people,” said the employee, who refused to give her name for print.

“This is B.S.,” she said. “If they can do a $200 million state study and fix the ditch up there, give some money to the hospital.”