Demise of TMT could have devastating long-term impact on Hawaii, supporters say

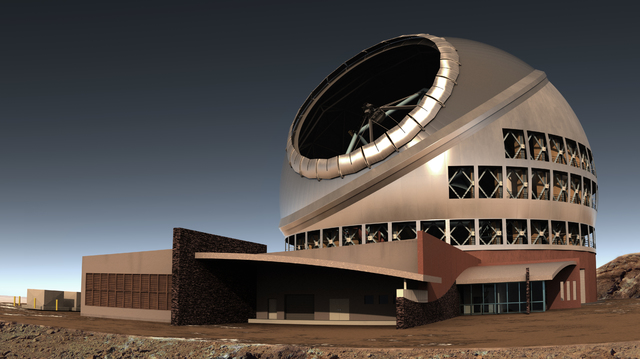

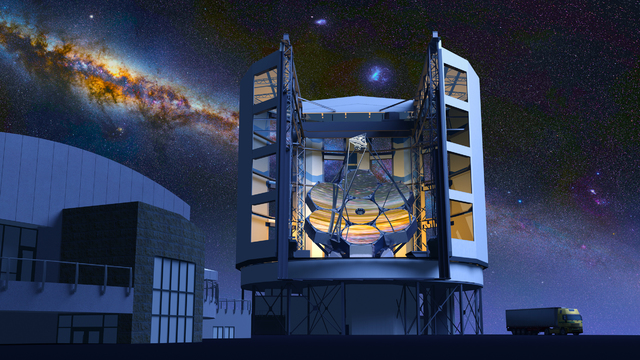

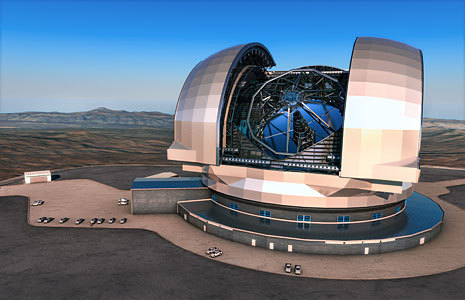

Within the next decade, the most powerful and largest telescopes ever created will begin catching starlight from across the cosmos, allowing astronomers to study the universe with greater clarity and perhaps answer some of humanity’s deepest questions.

What happened at or following the dawn of creation? Are there other worlds that support life?

But with Hawaii’s own contribution to this next generation of astronomy — the Thirty Meter Telescope — facing a tidal wave of opposition from those who want to either stop development on Mauna Kea or see all telescopes removed, scientists here are beginning to ask questions that hit closer to home.

If the protests prompt Hawaii to pull its support for the state-of-the-art observatory after it was approved, what is the future of astronomy on Hawaii Island? Or, for that matter, will there be a future for the science here at all?

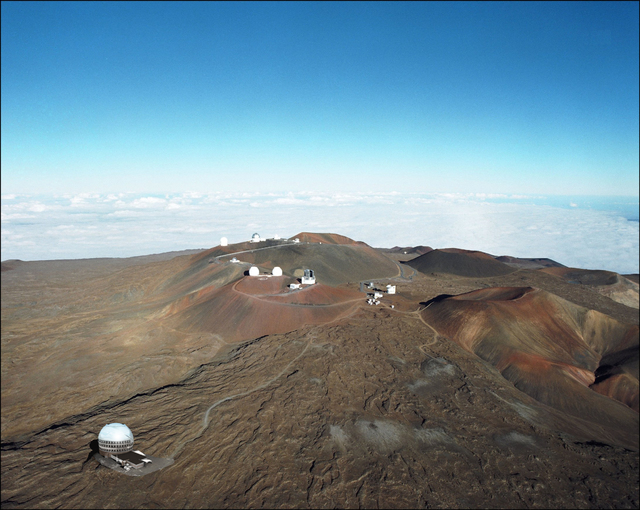

Considering Mauna Kea’s status as the top spot for ground-based astronomy and the approximately $58 million a year it contributes to the island’s economy, the answers to those questions come with profound impacts locally and globally.

Projections from astronomers and business leaders offer a grim outlook.

After more than a month of construction delays due to protests, they say they worry the state could be heading toward a debacle worse than the loss of the Superferry if construction is derailed. That would be a blow to astronomy that would be difficult for the industry to recover from, astronomers say.

“Everything was done in a correct way,” said Guenther Hasinger, director of the Institute for Astronomy at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. “If that doesn’t lead to completion of the building of the project, then the trust in the system will be gone.”

He’s not alone in that viewpoint.

Doug Simons, executive director of the Canada-France-Hawaii telescope, says losing the TMT after it was approved would be disastrous, and not just for astronomers.

“That sends an absolute chilling signal worldwide about federally funded scientific research in Hawaii,” he said.

The issue, astronomers say, is not simply the potential for losing a telescope project. After all, plans for the outrigger telescopes for the Keck observatory were scrapped after a judge voided their permit.

What makes the TMT conflict different and more serious, they say, is that it has already gone through an extensive approval process and so far cleared its legal challenges.

The process included an environmental impact statement, a contested case hearing that allowed opponents to argue against the project before a hearings officer, and an appeal of the conservation district land use permit in 3rd Circuit Court. Judge Greg Nakamura upheld the permit. (Another appeal of the permit remains pending in the state Intermediate Court of Appeals).

If protests alone stop the $1.4 billion project, supporters warn it would make it nearly impossible to justify additional investment in existing telescopes, and any new projects would be off the table.

“And it won’t be something that takes 10 to 20 years to see happen,” Simons said. “It will happen in the next year of TMT not getting built.”

In addition to putting a freeze on new telescope construction or investment on the mountain, Hasinger said stopping the TMT now based on the current opposition also would threaten the university’s attempts at getting a new master lease for the Mauna Kea Science Reserve, needed for observatories to operate beyond 2033.

“If we now lose the TMT, we would also lose the lease extension,” he said.

That matters not only for the role the telescopes play in science, but also the economic boost the Big Island gets from the industry, said Paul Brewbaker, a former Bank of Hawaii economist who operates his own consulting firm.

In a global economy, “everyone sort of finds their thing that they do better or more efficiently,” he said. Brewbaker sees astronomy as filling that role for the Big Island, which doesn’t have much else to rely on except for agriculture and tourism.

“Those reputations, as they say, are really hard to build,” he said. “When it’s just dog luck that you are endowed with it, it’s really easy to mess up and much harder (to recreate).”

A study by the University of Hawaii Economic Research Organization estimated the astronomy industry contributed $58.43 million in spending and supported 806 jobs on the Big Island in 2012.

Brewbaker said losing TMT would make it more difficult to attract investment in large projects here.

“It says the process is not credible and Hawaii is not a credible host to offer investment,” he said.

Barry Taniguchi, KTA Super Stores CEO and president, also was offering a dire outlook.

“They met all the rules,” Taniguchi said of TMT. “If Hawaii were to pull back on this, I believe, as an independent business man, we are going to give Hawaii a black eye.” He was a founding member of the Office of Mauna Kea Management board.

Kealoha Pisciotta, a Hawaiian cultural practitioner and former telescope technician, disagrees with the view that TMT has done everything right through the process. She is one of six petitioners who participated in the contested case hearing and who are continuing to appeal the project’s land use permit.

Pisciotta said there is already broken trust within the Hawaiian community, and she doesn’t believe UH deserves to get a lease extension.

“This delusion on the UH astronomers’ part has kept them from not only understanding the issues at hand, but has allowed them to ignore their own negative role in the long, sad history of the American colonization of Hawaii,” she said in an email to the Tribune-Herald. “It’s time for UH and the greater astronomy community to really listen with their heart.”

Pisciotta said it would be better to have the mountain fully restored without the telescopes due to cultural sites in the area and environmental concerns.

“These are all the reasons why Mauna Kea is designated as a Conservation District and why it is protected by the law,” she said. “Protecting these important things ensures our ability to survive and thrive into the future.”

While opponents see the 180-foot-tall telescope as a desecration of a sacred mountain, supporters see a model for other observatories to follow.

Greg Chun, OMKM board member and former Kamehameha Schools vice president, said TMT has set a new standard with its closed waste system, substantial lease payments and investments in education and workforce development on Hawaii Island.

“Doing astronomy on the mountain, from our perspective, is a privilege,” he said. “And with that privilege comes a heck of a lot of responsibility. TMT has raised the bar for everyone as to what it’s going to take to operate up there anymore going forward.”

Supporters also acknowledge that they are not dealing just with the merits of the project, but the legacy of development that has created a complex of 13 telescopes on top of Hawaii’s largest and most culturally significant mountain.

Simons said he understands where the frustration is coming from.

He was an astronomer here in the 1990s when a critical state audit faulted the university for mismanagement of the mountain. That led to the creation of OMKM under UH-Hilo and plans to protect natural and cultural resources.

“A lot of good things happened as a result of protests done in the ’90s,” said Simons, who also sits on the OMKM board.

Pisciotta said reforms still fall short.

“Not by a long shot,” she said, when asked if the university has done enough.

While TMT would be the 14th telescope on the mountain, OMKM Director Stephanie Nagata said that number is expected to decrease to about 10 over the next couple decades as older observatories meet the end of their useful life. UH is currently trying to set more definite decommission timelines for up to three older observatories.

The actual number of telescopes would depend on whether observatory sites are recycled as older ones are decommissioned. UH has said TMT, which would be built at the 13,150-foot elevation on the north side of the mountain, would be the last new telescope site on Mauna Kea.

While hoping for middle ground, Simons said he worries that the era of social media and calls by some protesters for the removal of all telescopes could make it more difficult to find solutions this time around.

“Even if I don’t know what the middle ground is, I strongly suspect careful listening and clear and meaningful conversation is the avenue for middle ground,” Simons said.

“And,” as a practicing Catholic, “I’m a huge advocate for co-existence between science and religion.”

Email Tom Callis at tcallis@hawaiitribune-herald.com.