Strikes proliferate in China as working class awakens

NANLANG TOWNSHIP, China — Timid by nature, Shi Jieying took a risk last month and joined fellow workers in a strike at her handbag factory, one of a surging number of such labor protests across China.

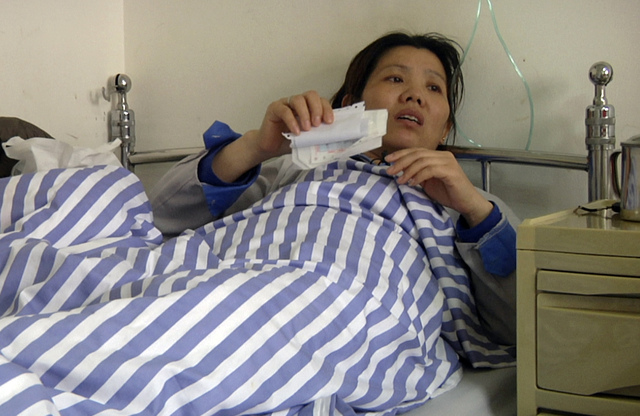

Riot police flooded into the factory compound, broke up the strike and hauled away dozens of workers. Terrified by the violence, Shi was hospitalized with heart trouble, but with a feeble voice from her sickbed expressed a newfound boldness.

“We deserve fair compensation,” said Shi, 41, who makes $4,700 a year at Cuiheng Handbag Factory in Nanlang, in southern China. Only recently, she had learned she had the right to social security funding and a housing allowance — two of the issues at stake in the strike.

“I didn’t think of it as protesting, just defending our rights,” she said.

More than three decades after Beijing began allowing market reforms, China’s 168 million migrant workers are discovering their labor rights through the spread of social media. They are on the forefront of a labor protest movement that is posing a growing and awkward problem for the ruling Communist Party, wary of any grassroots activism that can threaten its grip on power.

“The party has to think twice before it suppresses the labor movement because it still claims to be a party for the working class,” said Wang Jiangsong, a Beijing-based labor scholar.

Feeling exploited by businesses and abandoned by the government, workers are organizing strikes and labor protests at a rate that has doubled each of the past four years to more than 1,300 last year, up from just 185 in 2011, said Hong Kong-based China Labor Bulletin, which gathers information from China’s social media.

“What we are seeing is the forming of China’s labor movement in a real sense,” said Duan Yi, the country’s leading labor rights lawyer.

That’s prompted crackdowns by authorities, and factory bosses have fired strike organizers. Although authorities have long ignored labor law violations by companies, activists say authorities now dispatch police — and dogs, in at least one case — to factories to restore order or even restart production. They have also detained leading activists and harassed organizations that help workers.

China’s labor law, which went into effect in 1995, stipulates the right to a decent wage, rest periods, no excessive overtime and the right of group negotiation.

Workers are allowed to strike, but only under the government-controlled All China Federation of Trade Unions — which critics say is essentially an arm of the government that has failed to stand up for workers.

Workers who organize on their own can be arrested, not for striking but on charges such as disrupting traffic, business or social order. In Shenzhen, worker representative Wu Guijun was charged with gathering crowds to disrupt traffic, but was released with no conviction after a year in detention.

Migrant factory workers are perhaps the vanguard of this movement, but labor activism is slowly spreading among a working class that, all told, forms more than half of China’s 1.4 billion.

“The working class has not yet fully woken up,” said Qi Jianguang, 27, who was sacked from his job at a golfing equipment company in Shenzhen for leading a strike last summer. Lack of effective organization is another challenge. But he said that a common appeal for equitable and dignified treatment is serving to unite the laboring classes.

Deep suspicion of labor activism among authorities is rising. In February, the ACFTU’s party chief, Li Yufu, warned that hostile foreign forces were using illegal rights groups and activists to compete for the hearts of the workers, sabotaging the unity of the working class and of the state-sanctioned union.

Zhang Zhiru, who runs a small labor group helping workers defend their rights, has been repeatedly harassed by police. He said the government will continue thwarting efforts at labor organizations because it considers them “making trouble.”

But he remained optimistic.

“The social development and the increasing awareness of workers about their need to protect their rights will push the society forward,” he said.

In March, workers returning from the Chinese New Year break to the thousands of factories in the Pearl River delta region near Hong Kong staged three dozen strikes at companies such as Stella Footwear, Meidi Electronics and Hisense Electronics.

Some fight for mandated severance pay, some for back social security payments and some for equal pay for out-of-town workers who typically earn less than local city residents. All of these actions have been on factory grounds because workers have grown impatient with government mediation rooms or courts.

“In many cases, lawsuits cannot ensure that workers’ rights are protected, so the workers now are turning to collective negotiations or even organizing into a group to gain more, and to save time,” Duan said.

While many labor activists have been harassed and detained, few have been convicted. In the only known case of workers involved in organized actions being criminally punished in recent years, Meng Han and 11 other security guards at a state hospital in Guangzhou were convicted in April 2014 of gathering crowds to disrupt social order after they staged a strike to demand equal pay and equal social security for local and out-of-town workers.

In the Pearl River Delta town of Nanlang, the handbag factory where Shi worked is one of many lining the main drag that leads to a group of parks honoring the town’s most famous son, Sun Yat-sen, and the 1911 revolution he led to build a republic in China.

Earlier this year, the 280 or so workers, mostly women, went on strike to demand a still-unpaid but promised bonus of about $150 for last year. They ended the strike when factory management shelled out the money.

But in early March, the bosses announced fewer overtime hours and fewer workdays due to the global economic slump, and yanked a $5 bonus given to every female worker on March 8, International Women’s Day.

The workers went on strike again, demanding back payments into social security funds, housing allowances and — believing the factory was on its last legs — the right to a severance package if they quit.

This time, the management did not budge.

Inside the town’s government building, a Japanese man who identified himself as the factory’s former general manager but declined to give his name said through an interpreter that the company had no choice but to cut hours when it failed to receive enough orders. He said workers kept making new demands, and that the factory had to call in police after surveillance cameras showed workers engaged in sabotage.

A Nanlang government statement said it dispatched a team March 24 to persuade the workers to return to work, but that some of them were flattening tires, destroying a surveillance camera, displaying banners and preventing other workers from returning to the workplace. Four workers were detained.

Workers said they were holding a peaceful rally when police attacked them.

“They were pulling our hair, smashing cell phones so we could not take photos,” said a worker who gave only her family name, Cao. She was later taken to a police station, where she said she was handcuffed, deprived of sleep and food, and was lectured on her wrong behavior before being freed the next morning.

“I told them we are defending our own rights,” Cao said. She and 10 other workers were fired.

Shi, who had been hospitalized after the police raid, said the incident eroded her trust in authorities.

“We were hoping the government would be on our side,” she said, “but how could we have ever imagined that we would see the police pour in instead.”