CONCORD, N.H. — There is near universal agreement that the Northeast has to expand its energy supply to rein in the nation’s highest costs and that cheap, abundant, relatively clean natural gas could be at least a short-term answer. But

CONCORD, N.H. — There is near universal agreement that the Northeast has to expand its energy supply to rein in the nation’s highest costs and that cheap, abundant, relatively clean natural gas could be at least a short-term answer. But heels dig deep when it comes to those thorniest of questions: how and where?

Proposals to build or expand natural gas pipelines are met with an upswell of citizen discontent. At the end of last year, a Massachusetts route selected by Texas-based Kinder Morgan generated so much venom that the company nudged it north into New Hampshire — where the venom is also flowing freely. During this winter’s town meetings, a centuries-old staple of local governance in New England, people in the nine towns touched by the route voted to oppose the project.

That Northeast Direct line is one of about 20 pipeline projects being proposed throughout the Northeast, where savvy environmental and political forces combine with population density to provide a formidable bulwark. There’s another reason the loudest protests are all coming from the region: They’re where the gas is, waiting just east of the gas-rich Marcellus Shale region.

“Everyone seems to know the Northeast has a pipeline capacity problem, but not many seem to be willing to make many concessions to fix that problem,” said Andrew Pusateri, senior utilities analyst for Edward Jones.

And these are folks who pay a lot to stay warm in the winter and keep the lights on in summer. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, New Englanders paid $14.52 per thousand cubic feet of gas in 2014, compared to $10.94 for the rest of the nation. ISO-New England, which operates the region’s power grid, said in its 2015 Regional Electricity Outlook that natural gas availability is “one of the most serious challenges” the region faces as more coal and oil units go offline.

The Kinder Morgan plan would take gas from the plentiful Marcellus Shale region of Pennsylvania and pump it through a 36-inch line from Wright, New York, to Dracut, Massachusetts. Along the way, it would cut across a 70-mile stretch of southern New Hampshire, tickling the Massachusetts line. About 90 percent of the project would be along an existing power line corridor.

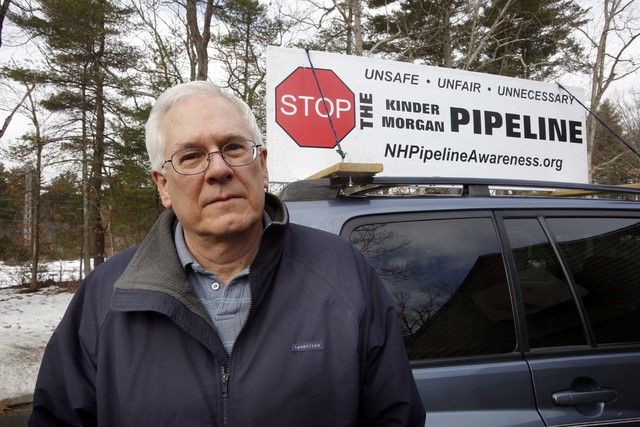

Homer Shannon and his wife raised three children on their suburban plot in Windham, New Hampshire, where the pipeline would pass a few hundred feet from their house. The retired high-tech salesman is part of a 10-family group of neighbors opposed to the pipeline’s route.

“This whole Northeast Direct thing is just fraught with question marks,” Shannon said. “Why in the hell is it in New Hampshire anyway? They want to get it from New York to Massachusetts and if you draw that line on a map, it sure doesn’t go through New Hampshire.”

Opponents — on the route and far from it — worry about environmental and scenic harm, lower property values, the potential for accidents and the idea that relying on natural gas only forestalls a switch to more renewable sources like wind or solar.

“It would be really nice if, as a region, we had a coherent energy policy that stated, ‘These are the things we need to do to improve our energy situation,’” Shannon said. “And if one of those things is I have to sacrifice part of my backyard for the greater good, I’d be willing to have that discussion. But I don’t see it that way. I see it as them enriching themselves on my back and I don’t like that.”

In New York and Pennsylvania, the 124-mile Constitution Pipeline has also fanned flames of opposition, some of it pegged to the price the gas company is paying to take land. Of 651 landowners in New York and Pennsylvania affected by the $700 million pipeline project, 125 refused to sign right of way agreements. Condemnation proceedings undertaken by Constitution have largely resolved the remaining disputes, either through settlements or access granted by a judge.

Donald Santa, president and CEO of the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America, said it follows that the most complaints would come from the Northeast because that’s where most of the pipeline activity is happening, largely because of the boom enabled by the Marcellus Shale.

“Having so much of this gas literally on the doorstep of the market has really increased the need to get the gas to consumers,” Santa said.

Richard Wheatley, a spokesman for Kinder Morgan, said the company’s pipeline is not the only one getting pushback. He declined to address the opposition specifically but said the company continues to reach out to landowners and others as the siting process moves along. The company expects to file a certificate with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission this year.

Pusateri, the Edward Jones analyst, said part of the resistance may also be inflamed because of how the gas gets out of the ground. The Marcellus Shale gas is extracted using hydraulic fracturing, or fracking. The process, which blasts chemical-laden water into wells to crack open rock, has drawn heavy criticism. In New York, much of the antipathy toward pipelines was driven by the anti-fracking sentiment that resulted in Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s ban on shale gas development in New York.

“All major projects have some opposition, but I would say this pipe has garnered more attention and protests and gained more steam than average,” he said. “I think Kinder has done what they can to move the right of way of the pipe as much off of people’s property as possible. They can do this by utilizing utility easements at times. I don’t know that opposition really softens.”